Why Can’t We Be Friends?

Friendship is “love without his wings,” aphorized the very volant Lord Byron, coining an apothegm that would be borrowed by Louis Auchincloss for the title of his excellent book on literary friendships.

But wings are an overrated appendage, aren’t they? For there is a serious upside to the inability to take flight: It keeps one grounded, and tamps the impulse to flee. Or as the alt-country singer Robbie Fulks asked, “Wouldn’t we all have wings/If God loved goodbyes?”

We live in a ridiculous age in which politics has become so central to so many sad lives that friendships are now bewinged. Disagreements over such nullities as AOC and Joe Biden are the source of ruptured relationships and bitter words that can never be taken back. (As a wingless attorney buddy of mine advises those seeking a divorce, “Never underestimate the value of the unexpressed thought.”)

Only one friend—a D.C. would-be denizen of the Deep State—has ever broken relations with me over politics. He severed the cord upon comprehending the full extent of my rejection of the catechism of the Church of Empire. (He was an advocate of what he would call a robust and activist foreign policy.) I thought he was kidding when he sternly lectured me so many years ago against taking a walk on the pacific side. I mean, who gives a damn if we disagree over NATO and Nicaragua, or the relative merits of Robert A. Taft versus Harry Truman? It’s not like either one of us has a lick of influence.

But a quarter century of radio silence suggests that we ain’t ever gonna drain beers again at the Tune In or the Hawk ’n’ Dove or any of those old Capitol Hill bars that may not even exist anymore.

Once again the virtues of anarchy hove into view. “Power is poison,” said the self-professed “conservative Christian anarchist” Henry Adams, and if there are no effective antidotes—the U.S. Constitution has done little to restrain the power-mongers, just as the Anti-Federalists predicted—why not strike at the root and abolish political power?

Absent the coercive state, political tiffs would be about as divisive as a dispute over which soft drink one prefers: Coke or Pepsi. Or, more accurately, Diet Royal Crown or Lemon-Lime Tab.

Till that happy far-off day, we should take as our models those who understand that politics must always be subordinated to friendship. I think of Henry Clay Owen, the staunch Hoosier Republican editor of the Terre Haute Post, who in 1920 endorsed for president the admirable Socialist Party standard-bearer Eugene V. Debs because Debs—recently sprung from the federal hoosegow, where he’d been caged for “sedition”—was such a good “neighbor and friend.”

Friendship, neighborliness, and the defense of Terre Haute against the impersonal forces that would denature that fair city were far more important to Owen and Debs than mere disagreements over, say, the ownership of the means of production. (The amiable Debs was also a good friend to James Whitcomb Riley, the Hoosier Poet, the frost on whose punkin’ was no shade of red.)

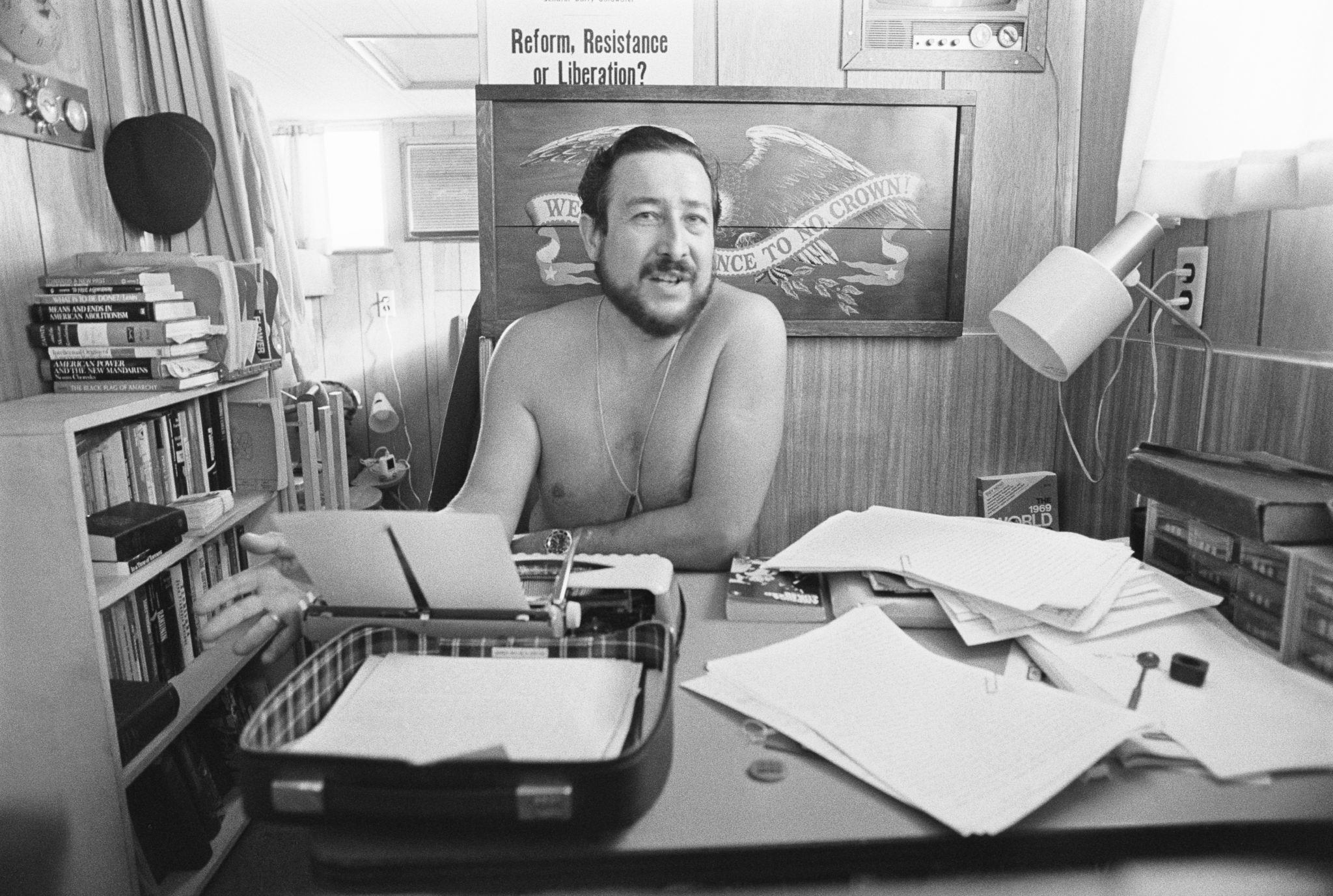

Too, we might take a cue from Barry Goldwater, Mr. In Your Heart You Know He’s Right (“in your guts you know he’s nuts,” cracked his foes), and his speechwriter and friend, Karl Hess. Karl, one of the great characters of modern American political life, dropped out of the incipient Conservatism, Inc., in the late 1960s. He traded in his tie for a workshirt, took up welding, and joined the Wobblies. Hess explained: “Vietnam should remind all conservatives that whenever you put your faith in big government, for any reason, sooner or later you wind up as an apologist for mass murder.”

The story is told of one incendiary antiwar demonstration outside the Capitol. Even the usual peace-and-justice congressional orators passed on this one—the potential for harmful publicity was just too high. To the astonishment of the protesters, only one politician showed up: the prowar Republican senator from Arizona, Barry Goldwater, who wandered through the shaggy-haired and combat-booted multitude asking the demonstrators, “Where’s Karl? Where’s Karl Hess?”

The story is told of one incendiary antiwar demonstration outside the Capitol. Even the usual peace-and-justice congressional orators passed on this one—the potential for harmful publicity was just too high. To the astonishment of the protesters, only one politician showed up: the prowar Republican senator from Arizona, Barry Goldwater, who wandered through the shaggy-haired and combat-booted multitude asking the demonstrators, “Where’s Karl? Where’s Karl Hess?”

He found him. Karl and Barry shook hands. Neither changed his mind about the war or capitalism, but so what? The warm clasp of friendship was what mattered.

In my wanderings I’ve broken bread and shared laughs with Black Panthers and New Leftists, neocons and neo-Confederates, the rock-ribbed and the bleeding of heart. Our political differences were real and worth arguing over, but each and every one of us was and is a child of God. None of us had wings, and I’m glad of it.

Bill Kauffman is the author of 11 books, among them Dispatches from the Muckdog Gazette and Ain’t My America.

Comments