What is MasterClass Selling?

MasterClass—the online educational platform that offers classes by “geniuses” in various subjects—has been a huge success, but what is it selling exactly? An education, entertainment, pipe dreams? Carina Chocano writes about how MasterClass was started and where it’s going:

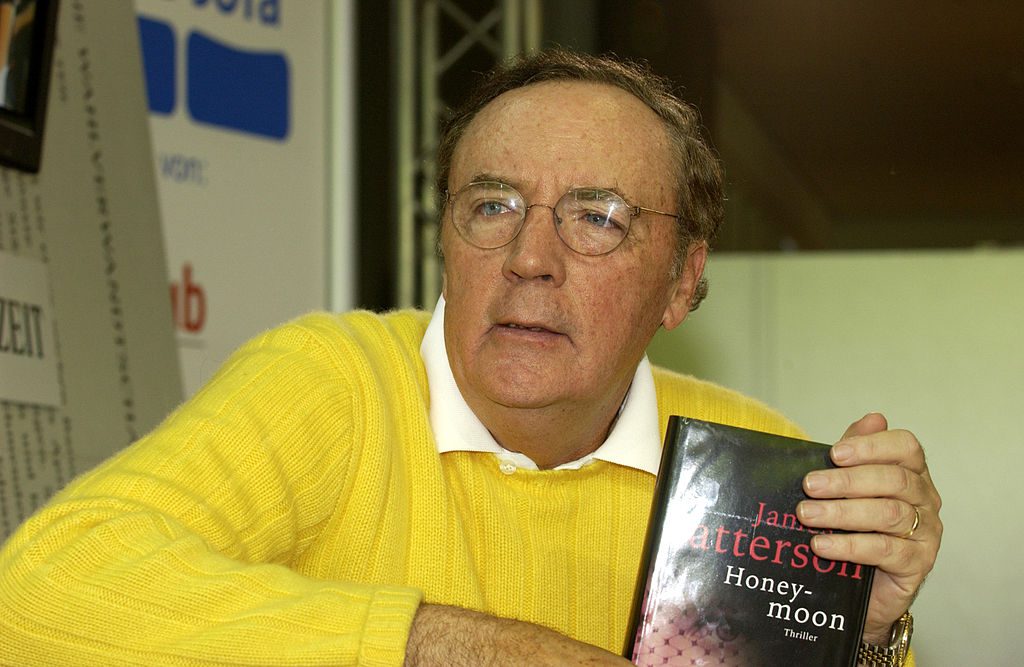

Sometimes an advertisement is so perfectly tailored to a cultural moment that it casts that moment into stark relief, which is how I felt upon first seeing an ad for the mega-best-selling writer James Patterson’s course on MasterClass a few years ago. In the ad, Patterson is sitting at a table, reciting a twisty opening line in voice-over. Then an overhead shot of him gazing out a window, lost in thought like a character in a movie. A title card appears: ‘Imagine taking a writing class from a master.’ It didn’t matter that I’d never read a book by Patterson before—I was hooked. What appealed to me was not whatever actionable thriller-writing tips I might glean, but rather the promise of his story, the story of how a writer becomes a mogul. Any hapless, hand-to-mouth mid-lister can provide instructions on outlining a novel. MasterClass dangled something else, a clear-cut path out of the precariat, the magic-bean shortcut to a fairy-tale ending—the secret to ever-elusive success.

MasterClass launched in 2015 with just three classes: Dustin Hoffman on acting, Serena Williams on tennis, and Patterson on writing. Since then the company has grown exponentially, raising $135 million in venture capital from 2012 to 2018. It now has more than 85 classes across nine categories. (Last year it added 25 new classes, and this year it intends to add even more.) After the pandemic hit, as people started spending more time at home, its subscriptions surged, some weeks increasing tenfold over the average in 2019; subscribers spent twice as much time on the platform as they did earlier this year. In April, the company moved from offering individual classes for $90 a pop, with an all-access annual pass for $180, to a subscription-only model, and in May, it raised another $100 million.

* * *

MasterClass’s mission, as it was originally defined, was to ‘democratize access to genius.’ But the service actually offers something different—although what that is, exactly, is hard to put your finger on. Strictly speaking, a master class is a small class for very advanced students taught by a master in their field. But very advanced students in particular subject areas are vanishingly small cohorts—certainly not enough to attract hundreds of millions of dollars in investments. And so, MasterClass courses are not really designed for a specific skill level, but instead are aimed at the most general of general audiences.

In other news: Eduard Habsburg writes a delightful review of a new history of his family: “If you are a young Habsburg in school and the topic of the Habsburg family arises – as it quite often does, believe me – the history teacher will look at you and say something like: ‘But obviously, Mr Habsburg, you would know that.’ The entire class swivels around and looks at you. You blush furiously. And more often than not, you don’t know. No, we Habsburgs are not born with an innate knowledge of our family history, and apart from some trivia handed down from generations, we have to work our way into our family history like most other people. Often friends on Twitter ask me: ‘Is there a good book I should read if I want to learn about your family?’ Which brings me to Martyn Rady’s brand spanking new The Habsburgs: The Rise and Fall of a World Power.” (HT: Richard Starr)

Adin Steinsaltz spent 45 years translating the Babylonian Talmud. He died on Friday. He was 83.

You may already know this, but Jimmy Lai, the publisher of Hong Kong’s prodemocracy newspaper, Apple Daily, was arrested.

The decline of wit: In Ken Burns’s 1994 documentary series Baseball, Bill McMorris writes, we are “regaled for more than 18 hours with not only box scores and controversy but also the quips of those who populated the game. But a funny thing happens midway through the last two-hour episode, which covers the game from the ‘70s to the ‘90s: The wit disappears. It happened right as we stopped referring to teams as ball clubs and started calling them ‘organizations’ and brands.”

Stephen Schmalhofer writes about the stammering wit of Wall Street, William Riggin Travers: “Travers was unable to speak more than three words without stammering. He achieved his reputation as a great wit despite, or perhaps because of, his stutter. If he could not eliminate his speech impediment, he would use it with precision.”

Travers, as it turns out, was a roommate William Tecumseh Sherman at West Point. Rich Lowry reviews a new biography of Sherman in National Review: “If the mob wanted to take sledgehammers and grappling hooks to statues of Sherman, it would have grounds to do so — his retrograde racial attitudes; his campaign of property destruction in the South; his role in the Indian wars. Yet none of this can detract from his gargantuan contribution to the salvation of the nation in the Civil War, and his enormously impressive qualities as a warrior-intellectual: a prodigious reader, bracing writer, and student of the arts — who also happened to capture Atlanta.”

RealClear has put together a helpful collection of articles responding to the 1619 Project. Check it out.

Photo: Grand Canal

Receive Prufrock in your inbox every weekday morning. Subscribe here.