We’ve Seen the Debates–And What Could Be Our Future

The Democratic Party on display over two nights of presidential debates this week would lead America into an experiment in leftist governance far beyond anything the country has seen before or even contemplated.

In immigration, economic policy, health care, climate change policies, and racial matters, the party is establishing, through the nascent presidential contest, a foundation for a serious lurch to the left should it capture the White House next year—and particularly if it manages to capture Congress at the same time.

Opposition Republicans should resist the temptation to view this development as a sign that the Democrats are on a political suicide mission. The country remains unsettled, as it was at the beginning of the 2016 campaign, with large population segments believing America is slipping into progressive dysfunction. Further, millions of Americans have concluded that the nation’s ills are attributable largely to that man in the White House, President Donald Trump, despised by many as a man beneath the office he holds. For them the corrective is simple: expunge Trump.

And Democrats will enjoy an advantage this time around. They can make their case with words, whereas the incumbent president must make his case with action and performance. In the last presidential race, that advantage fell to Trump, and he exploited it effectively, helped along by President Barack Obama’s mildly unsuccessful second term and lingering systemic problems besetting the nation. If Trump can’t bring in a clearly successful first term, he won’t likely get a second one, and the New Democratic Party will take over.

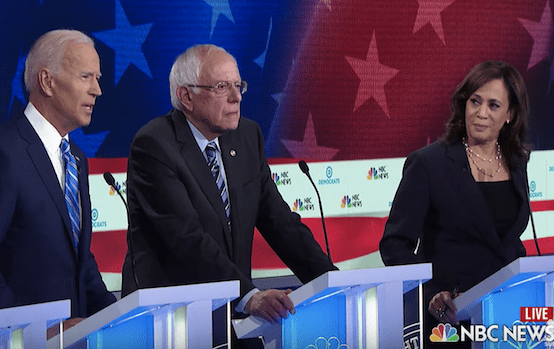

This week’s debates, held in Miami and hosted by NBC News, showcased 20 Democratic candidates who passed muster for inclusion through fundraising or poll performance. Some key conclusions emerged on the state of today’s Democratic Party.

The party is now an open-borders party. For years the effort to manage the issue centered on an elusive compromise concept that included serious border security and a path to legality or citizenship for current illegals. The problem for immgration restrictionists was that the last time such a compromise was struck, in 1986, it didn’t work. Amnesty was granted to illegals then in the country, but no serious border security ensued. Instead the number of undocumented residents shot up to 11 million or more.

The debates revealed that serious border security is not something most Democrats consider worth mentioning. Instead, most railed against the fact that crossing the U.S. border illegally is a criminal offense. They argued it should be merely a civil matter. “Don’t criminalize desperation,” said Julian Castro, U.S. secretary of housing and urban development under Obama. “What kind of country are we running here?” asked Ohio Representative Tim Ryan, with a president stoking “hate and fear.”

In the first debate, on Wednesday, only Ryan and Minnesota Senator Amy Klobuchar expressed concerns about eliminating criminal statutes for illegal entry. On Thursday, when NBC moderators asked for a show of hands of those who wanted to “decriminalize” unauthorized crossings, only Colorado Senator Michael Bennet kept his hand down. Also on Thursday, several candidates decried the idea of deporting illegal immigrants who hadn’t committed crimes in the United States, while no one expressed misgivings about such a policy. When it was pointed out by one NBC moderator that Obama had deported 3 million illegals during his presidency, California Senator Kamala Harris responded, “I disagreed with Obama on that.”

And when the Thursday candidates were asked if they would provide health care for illegal immigrants, all said they would. Also, no one at either debate expressed a concern about U.S. border facilities being overwhelmed by asylum seekers traveling as families and entering the United States illegally—some 332,000 since October. Instead they railed against U.S. officials struggling with the task of processing these people without adequate personnel or facilities.

In short, judged by the debates, the New Democratic Party has abandoned the old compromise concept of border security in exchange for a pathway to citizenship for current illegals. These candidates made clear that they continue to insist on a citizenship pathway but don’t care much about border security.

Democrats want big government to get much bigger. Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders, who calls himself a socialist, sets the tone with his call for Medicare for All, free education at public colleges and universities, the elimination of student debt, and government efforts to curtail big corporations, particularly insurance and pharmaceutical companies. He would tell those companies that “their day is gone,” said Sanders. While not all Democrats this week would go as far as Sanders, no one took him on in any serious way. Although only three other candidates joined Sanders in calling for a single-payer health-care system, several others said they favored it but only through a more measured phase-in approach. Former Vice President Joe Biden stood firm on the more incremental concept when he said, “I’m against any Democrat who opposes, takes down Obamacare—and then a Republican who wants to get rid of it.”

There was much agitation about economic inequality, with most candidates railing against the wealthy and labelling Trump’s 2017 tax overhaul as a sop to the very richest Americans. “The economy is doing great for a thinner and thinner slice at the top,” said Massachusetts Senator Elizabth Warren, but not for everyone else. She added, “And that’s corruption plain and simple.” Her point was echoed by others throughout the two debates, signifying a Democratic administration likely would seek to return the top individual tax rate to 70 percent or more, break up large corporations, bolster the regulatory state, and institute redistributive programs. As New York Mayor Bill De Blasio put it, “There is plenty of money in this country, it’s just in the wrong hands.”

Identity politics, a central element of the Democratic Party, still stirs emotions. Those emotions erupted in the Thursday debate when Kamala Harris took on Biden for his earlier remarks about the old days of the Senate when he could work collaboratively with Southern segregationists such as Alabama’s James Eastland. Harris said it was “very hurtful” to hear Biden “talk about the reputations of two United States senators who built their reputation and career on the segregation of race in this country.” She scored Biden also for working with such senators in opposition to busing for racial balance in schools during the 1970s.

“Do you agree today, do you agree today that you were wrong to oppose busing in America then? Do you agree?” she asked with considerable emotion in her voice. She added it was a personal matter with her given that she had benefited from busing policies as a young girl.

Biden retorted: “A mischaracterization of my position across the board. I did not praise racists.” He added that he never opposed busing as a local policy arrived at through local politics, but didn’t think it should be imposed by the federal government. “That’s what I opposed,” he said.

The exchange accentuated the extent to which racial issues are gaining intensity in America and roiling the nation’s politics to a greater extent than in the recent past. Biden’s point, as he sought to explain, was that there was a day when senators of all stripes could work together on matters of common concern even when they disliked and opposed each other’s fundamental political outlook. That kind of approach could point the way, he implied, to a greater cooperative spirit in Washington and to breaking the current political deadlock suffused with such stark animosities. But that merely stirred further animosities, raising questions about whether today’s political rancor in Washington can be easily or soon ameliorated.

A strain of foreign policy restraint may be emerging in the party. It wasn’t surprising that Hawaii’s Representative Tulsi Gabbard, an outspoken advocate of realism in foreign policy, exploited every opportunity to highlight her opposition to what she considers America’s promiscuous warmaking policies of recent decades. She decried the country “going from one regime-change war to the next. This insanity must end.” But other Democrats also echoed that sentiment, particularly with regard to the growing tensions between the Trump administration and Iran. Bill de Blasio said he would oppose another Mideast war unless it is authorized by Congress. He added, “We learned a lesson in Vietnam that we seem to have forgotten.” Sanders also decried the possible drift to war with Iran as well as America’s involvement in the civil war in Yemen. He expressed pride in his opposition to the Iraq war and chided Biden for supporting that 2003 invasion.

Three candidates—Klobuchar, New Jersey Senator Cory Booker, and Gabbard—criticized Trump for getting out of the Iran nuclear deal. “I would sign back on,” said Gabbard, saying a war with Iran would quickly ignite the entire region and would be “far more devastating and costly” than the Iraq war. When Ryan suggested we must remain engaged in the Middle East, Gabbard called that “unacceptable” and added the United States has nothing to show for its 18-year mililtary campaign in Afghanistan. At the conclusion of the debate, Gabbard became the most searched candidate on Google, according to a report on Fox News that cited Google Trends data. Could this mean a gap persists between the foreign policy sentiments of many Americans and the foreign policy activities of their government in Washington?

The party’s connection to heartland voters remains up in the air. Tim Ryan talked about the party being too much of a “coastal” party, and even uttered the word elitist to describe his party. “If we want to beat Mitch McConnell, this better be a working class party, a blue collar party,” he said. Bill de Blasio added, “We need to be a party of working people again.” But these comments didn’t stir much comment or apparent interest from others on the stage, and the candidates didn’t seem particularly focused on the party’s recent alienation from the kinds of non-college whites who once constituted the Democratic backbone. And the party’s positions on immigration and identity politics may not enhance prospects for that kind of conciliation. De Blasio may have crystallized the problem when he said, “For those who feel that they have been left behind, immigrants didn’t do that to you. Big corporations did that to you. The top 1 percent did that to you.”

If Democrats can sell that concept to those working class types that Ryan and De Blasio were talking about, perhaps the Democrats can lure back into the fold those industrial battleground states that were lost in 2016. But it could be a tough sell.

Robert W. Merry, longtime Washington journalist and publishing executive, is the author most recently of President McKinley: Architect of the American Century.

Comments