There’s No Such Thing As ‘Suburbia’

I and my fellow writers here have often written critically about suburbia: see “What to Do When Suburbia is Your ‘Hometown,’” “Suburbanizing History: Northern Virginia’s Identity Crisis,” and “The Slow Death of the Shopping Plaza.”

Reading the comments and Twitter reactions to these pieces, I realize there’s a question we should probably answer or at least discuss more often: what is “suburbia”? As the saying goes, know your enemy.

There’s no one answer to that question. The original meaning of “suburb” is mainly geographic—a suburb is a smaller, less densely populated settlement outside of a city. It can be a smaller city, a town, a residential outgrowth, or a sprawling “census-designated place.” But there’s also the post-World War II definition of “suburb” that refers to bedroom communities, commercial sprawl strips, and places like Levittown—suburbs in the geographic sense to be sure, but also “suburbia” in the sense of an automobile-dependent development pattern distinct from towns and cities.

Some commenters have suggested that in being critical of the suburbs, I am suggesting that everyone live in big cities. That’s not the case. Towns and small cities, though they will inevitably be suburbs of their larger metropolitan areas, are not the kind of places that the critics of suburbia are railing against. It is important, then, to start out with a definition of “suburb” that is based not on geography but on the form of the built environment itself.

This requires some basic knowledge of zoning laws, which are largely responsible for “suburbia”—places that are not cities, towns, or rural countrysides, but a different kind of built environment altogether. The fundamental zoning principle here is the separation of uses, known as single-use zoning. This is why suburbs from mid-century and later generally lack traditional main streets, mixed-use buildings (except for condo complexes with floor-level retail), and corner stores in residential areas. James Howard Kunstler has written extensively on how suburban zoning codes and other building ordinances are largely designed to support property values and keep the gravy train of suburban construction running, rather than create pleasant and satisfying environments for people.

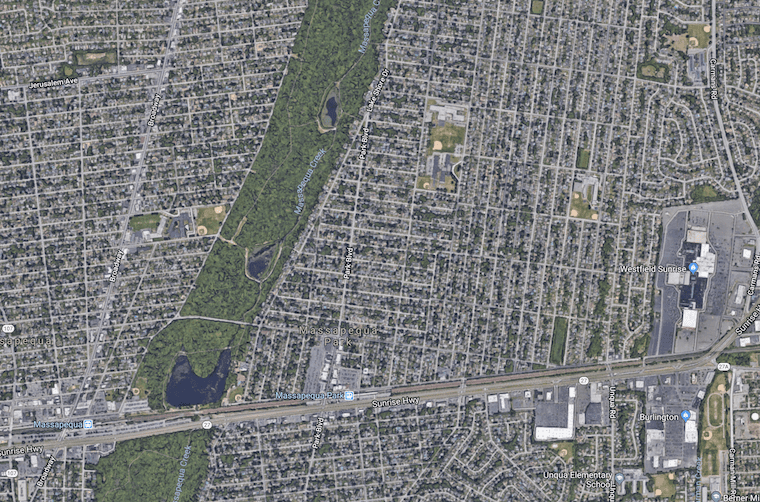

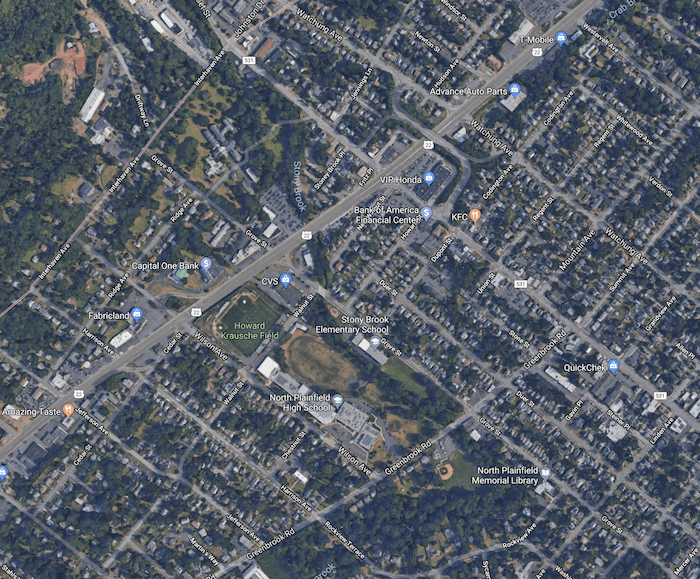

Still, there are different versions of suburbia, reflecting tweaks in zoning, economics, and time of construction. Midcentury suburbs that grew out of older pre-World War II settlements, like Massapequa Park, New York, or North Plainfield, New Jersey, are as different from the exurban fringes of Bozeman, Montana, or Leesburg, Virginia, as any of them are from true towns or rural countrysides. And perhaps the sprawling commercial wastelands that surround Interstate exits deserve their own special category.

First, there are those midcentury suburbs. Largely assembled between the mid-40s and the 60s, these places are distinct from later incarnations of suburbia. Many of them feature gridded streets of single-family homes clustered around a commercial highway strip. Some are expansions of an original older town, with the town structure preserved but the residential area greatly enlarged. There are often ballfields, churches, schools, and civic buildings amid the homes, echoing the mixed-use style of a true town (even Levittown has civic amenities sprinkled between the houses). Instead of dead-end cul-de-sac streets and collector and arterial roads, there are many gridded streets that intersect at right angles with the commercial strip, another town-like feature. There are almost certainly sidewalks, even on the highway. These types of places are generally lumped into the broad category of “suburbia,” but they probably get more hate than they deserve. This environment is, in fact, a modification of the traditional small town, in which the commercial highway strip replaces Main Street. In the parlance of paleontology, the gridded post-war suburb is a transitional species. It is suburban, but it is not quite sprawl.

Where can you find these places? In the inner rings around most major cities, and clustered along the highways leading into them. Many places in D.C.-adjacent Maryland qualify, as well as the New York City-adjacent communities along older highways like New Jersey’s Route 22 and Route 27. Many towns along Sunrise Highway, one of the main corridors on Long Island, follow the same pattern. While some inner-ring suburbs predate World War II, many were newly built or massively expanded in the 1940s and 50s—the point is that even the post-war construction was often adapted to the existing pre-war style rather than to the later sprawl style.

Take North Plainfield. The borough goes back to the 1800s, but expanded considerably in the midcentury period. However, it is more or less an extension of the city of Plainfield, which directly borders it to the southwest and is a true city, with a main street and multi-use, multi-story center. The street grid of Plainfield continues unbroken into North Plainfield, and the Plainfield main street drag is walkable to North Plainfield residents. North Plainfield itself, which fronts Route 22 for about two miles, is clearly a part of suburbia. But its status as an early, transitional form of suburbia is clear.

[googlemaps https://www.google.com/maps/embed?pb=!4v1523976768122!6m8!1m7!1swUbiGX09hj5TA6WtkDimlQ!2m2!1d40.67898509882461!2d-73.45576930520286!3f193.5609415239889!4f5.124877771445867!5f0.7820865974627469&w=600&h=450]

Main drag in Massapequa Park, N.Y. on Long Island. This was mostly built in the 50s, and unlike most main streets in true towns, lacks residential spaces above the retail.

Long Island’s Massapequa Park, with its Main Street-style retail district, gridded streets, and long strip of Sunrise Highway (the Route 22 of Long Island), places it in the same transitional category. The midcentury developments built along Maryland’s Route 193 (pictured above) do as well.

[googlemaps https://www.google.com/maps/embed?pb=!4v1523978398622!6m8!1m7!1sTjBPn5gMQdwszS4qiXlpvw!2m2!1d40.61960449087865!2d-74.4228159371514!3f230.86610174332645!4f1.0014940671890855!5f0.7820865974627469&w=600&h=450]

Main drag of Plainfield, N.J. The street grid in Plainfield continues identically in the later and more suburban North Plainfield, which fronts the main regional highway.

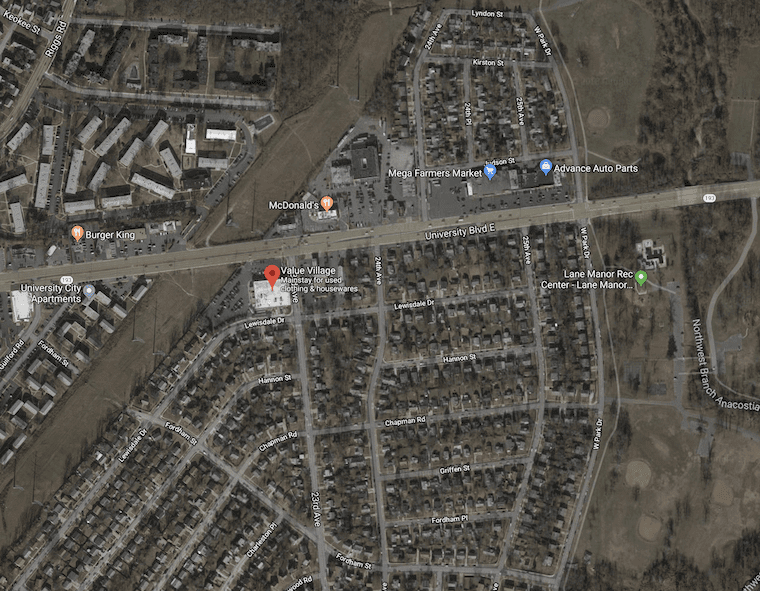

Interestingly, even within the same geographical area, you can find a different kind of suburb: the more modern sprawling subdivisions. These are relatively dense but not gridded, featuring cul-de-sacs and 40-foot-wide corkscrew roads. There are no ballfields, churches, or anything else amid the homes. At most, they might be at the edges of the subdivision developments. Separation of uses is stricter here, and there is no longer even a ghost of a small town. Milk and eggs is now a drive, not a walk, away. These places are generally newer and richer. Here are two aerial photographs of New Jersey showing North Plainfield to the south of Route 22 and Watchung to the north. Route 22 runs diagonally through the middle. The first is from 1957, showing the street grids to the south and a few nascent streets in the forest. The second is from 2013 (it looks the same today), showing the subdivisions that have taken over.

And then there are the “exurbs”—countrysides into which various trappings of suburbia suddenly crop up, as if airdropped in during the night. You pass forests, silos, farmhouses, tiny timeworn towns, and gravel roads, and then suddenly a massive Lowe’s or Walmart.

[googlemaps https://www.google.com/maps/embed?pb=!4v1523911515417!6m8!1m7!1sBBHgz2jG-sWSkenWrLw0zw!2m2!1d45.67131332387583!2d-111.0784331804901!3f138.3526942565944!4f-8.53975868650194!5f0.7820865974627469&w=600&h=450]

Recent, very large retail developments amid largely undeveloped space outside Bozeman, Mont. (above) and Leesburg, Va. (below)

[googlemaps https://www.google.com/maps/embed?pb=!4v1523911644888!6m8!1m7!1sUvIQhwBy2bbDYOLb-ZAS8Q!2m2!1d39.09060549312512!2d-77.52140676801643!3f182.16416662042585!4f-4.5418889300217415!5f0.7820865974627469&w=600&h=450]

Eventually, many of these places will get so built up that they will lose any residual rural character: aerial photos reveal that much of Fairfax County and Alexandria, Virginia, were rural/exurban in the 1950s, and are now crowded and aging.

Some exurbs, however, will remain as they are or even shrink. Many of these places amount to failed experiments, their development having stalled after the financial crisis and never recovered. Some of the grand homes in far-out suburbs are worth even less now than before the Great Recession. Some were put on ice after the crash and are in a state of half-completion. Near my parents’ home in New Jersey, you can see an aborted attempt to build McMansion subdivisions within farm fields. Just as those early suburbs took on the street grids of earlier towns, these late suburbs literally take on the pattern of the fields.

There is virtually nowhere in the American landscape that has not been touched, or defiled, by suburbia, but suburbia is not one single pattern. Some forms are far less flawed than others. Surely the category could be parsed more precisely than I have done here. But next time any of us get negative about suburbia, at least we’ll have an idea of which kind we’re talking about.

Addison Del Mastro is assistant editor for The American Conservative. He tweets at @ad_mastro.