The Dimensional Impulse in the Western Artistic Tradition

Since Greco-Roman antiquity, the architecture, sculpture, and painting of the Western world has engaged mind and senses not only through different artistic media, but different modes of perception. This perceptual aspect, involving the distinction between pictorially-oriented and what we might call dimensionally-oriented modes of design, is generally unappreciated. We experience the distinction without being conscious of it. It is nevertheless a vital part of our civilization’s artistic heritage, and a little tour of works of architecture and fine art in our nation’s capital might help elucidate it.

Let’s begin with the handsome enfilade of Ionic columns along the eastern 15th Street flank of the U.S. Treasury Building, which is located next to the White House. The colonnade is essentially pictorial in its appeal. It offers a silhouette-like image of structural support. Many centuries ago, when builders first sketched classical columns and their superstructures, or entablatures, the result was a two-dimensional diagram of a horizontal load and its vertical supports in static equilibrium. Such images aligned with the pictorial mechanism of human vision: We see the world around us not in three dimensions, but as a two-dimensional picture, generated by the reflected light that the lens of the human eye projects onto its retinal “movie screen.” That logic informed the design of the Treasury colonnade.

foreground). Robert Mills and Thomas U. Walter, architects. (Ted Eytan/ Creative Commons)

But if we turn to the majestic dome of the United States Capitol, we encounter a more spatially continuous or dimensional form, intended to override the pictorial mechanism of human vision. There is a subtle but crucial distinction between spatial depth—which the retinal movie screen readily accommodates, showing us the world with foreground receding into background—and spatial continuity, which must be suggested or evoked. An august rendition of an Italian Renaissance form, the dome’s contours, far from suggesting a terminus or edge, seemingly lead the eye around it. Both the Treasury colonnade and Capitol dome are monumental structures. But they reflect distinct aesthetic motives.

Dimensional form was a later development. As the art historian Rhys Carpenter explained, its creation involved a revolt during Greece’s classical age against the pictorial constraints on archaic art. Think of those rigid, rather weirdly stylized Attic youths you’ve probably seen in some museum or other. They are quadrifrontal figures, but designed to be viewed from the front. They don’t lead you around them. Profiles were drawn on the four faces of marble blocks and the blocks were cut away on each side. The result was four pictorial profiles, with the anatomical forms—ears, eyes, hands, knees and so forth—amounting to flat, schematically patternized elements.

The impact of that Greek revolt can be observed in the gorgeous Aphrodite torso in Washington’s National Gallery of Art. It dates to the Hellenistic period, four centuries or more after those archaic youths were created. The sculpture is missing arms below the shoulders, lower legs and head, but it was manifestly designed to be experienced in the round. The figure’s weight is carried on one leg and there is subtle torsion in the pose. Far from being patternized, two-dimensional elements, the anatomical forms, most obviously the breasts, are very complex in their geometry. Creases in the flesh above and below the navel guide the eye around the figure, but the incredibly supple modeling has the more important role in this regard. We see contours, yes, but no pictorial edge. A photograph—a mechanically-generated optical record mimicking the mechanism of human vision—doesn’t reveal this dimensional quality fully. You have to experience the sculpture in the flesh.

By intensifying the figure’s spatial presence, this dimensional quality makes it more monumental. There is a passage in Pliny the Elder’s Natural History—based on the commentary of two Hellenistic sculptors who had lived several centuries before—demonstrating that artists consciously sought to create this effect. On the subject of draftsmanship, Pliny wrote, “[T]he [figure’s] outline should turn back on itself, thus leaving off in such a way that it promises other contours behind it and even reveals what it conceals.” Literary overstatement aside, that’s what’s happening in this Aphrodite torso. It’s what’s happening, more obviously, on the Capitol dome.

Highly skilled painters have aspired to achieve this dimensional effect in their figure work. A portrait of the Dutch master Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-1669) in the National Gallery, believed to be the work of a member of his workshop, employs the head’s three-quarter profile, the curving outlines of the hat and skullcap, and lighting to heighten its spatial presence. Michelangelo came to speak of “serpentine” form as an essential desideratum of figure sculpture. That means spiraling contours running around the torsional figure as opposed to mere curvaceous silhouettes. Remarkably, we see something of this concept, as well as Pliny’s stipulation, in the realm of 17th century Dutch landscape painting.

The National Gallery owns several canvases by the landscape master Meindert Hobbema (1638-1709). His View on a High Road offers pictorial S-curves—the winding road that is the picture’s centerpiece, the sinuous tree-trunks—but foreground does not simply recede into background. Through its arrangement of masses and spaces, and light and shade, the painting strongly suggests to the eye circuitous spatial trajectories by which “what goes ’round comes ’round.” The small pool of water the central road winds around serves as a visual vortex in this strikingly dynamic, subtly enchanting work. Despite the two-dimensional medium in which he worked, Hobbema, like other masters of the Dutch Golden Age, focused on the magical evocation of spatial continuity.

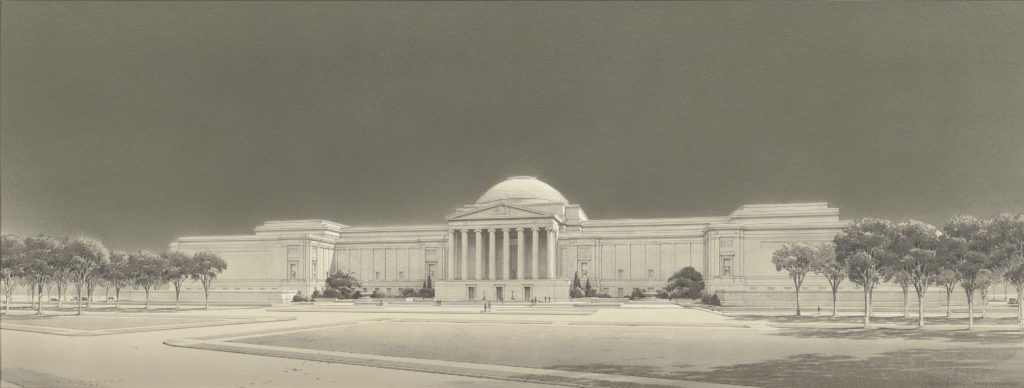

The advent of photography around 1840 undermined the dimensional impulse in western design, starting with the painting and sculpture of French academicians who unwisely embraced the new technology. Yet it is worth noting that the National Gallery’s West Building (1941), designed by John Russell Pope, represents a striking example of the dimensional impulse infusing a monumental design. Like the Capitol dome, Pope’s building contrasts with that 15th Street Treasury Building front, where the Ionic colonnade is terminated by slightly protruding pavilions at each end. The pavilions endow the building with terminating edges, which imbue it with pictorial spatial definition. It is precisely such terminating accents that are missing on Pope’s masterpiece. Beautifully proportioned masses and an exquisite array of cornice lines not only emphasize the building’s horizontality but suggest its “turning the corner,” as opposed to terminating, at each end. Pope wanted the edifice to evoke a sense of spatial continuity.

The aesthetic depth of Pope’s design is abjectly lacking in I.M. Pei’s National Gallery East Building (1978). The East Building’s main, west-facing front offers prismatic geometries that are certainly sharp-edged—not least the rather repulsive “knife edge” at the front’s south end, pitched at a 19-degree angle. Viewed from the east end of Pope’s building, Pei’s architectural forms recede, picturesquely, from foreground to background. The perversely disjointed design reflects the photographically-oriented “wow” sensibility that saturates modernist architecture. The East Building’s design is a negation of the classical idea of the harmonious composition of masses grounded, ultimately, in the forms and proportions of the human body. When you walk around the building you see that the composition as a whole is disjointed. It conveys no sense of organic unity, in contrast to the West Building. Pei’s building is not so much architecture as a bizarre structural contraption. Needless to say, modernist critics love it.

The dimensional aspect of the humanist design tradition originated in the Greeks’ unprecedented attentiveness to the distinction between what we see on our retinal movie screens and what is. Commentators speak of the “naturalism” or “realism” of Greek art relative to earlier, more primitive traditions, and that’s true enough. But they generally miss a cardinal aspect of the development of Greek art: the overriding of the pictorial mechanism of human vision through the creation of forms imbued with an intensified spatial presence—what we might call an intensified realism—far removed from our commonplace experience of nature. As we’ve seen, that Hellenic quest has paid rich dividends, right up to World War II, in different artistic media. In fine art especially, it demands enormous skill. What sort of future might it have? That is a question I will take up in future commentary for The American Conservative.

Catesby Leigh is The American Conservative’s New Urbanism Fellow. He writes about public art and architecture and lives in Washington, D.C. This New Urbanism series is supported by the Richard H. Driehaus Foundation. Follow New Urbs on Twitter for a feed dedicated to TAC’s coverage of cities, urbanism, and place.

Comments