The Foreign Policy We Need

Four years after the once unthinkable election of a Republican president who called the Iraq war a “mistake,” America still needs a genuinely conservative foreign policy of realism and restraint.

Hegemonists and hyper-interventionists are being challenged for the first time in two decades, perhaps as never before in the post-Cold War era. The folly of their never-ending, no-win wars is evident to voters, prime-time cable news hosts, diplomats, academics, even the veterans and active-duty soldiers who have fought in them. A new generation of conservative thought leaders is coming of age that turns the thinking that prevailed under George W. Bush on its head, yet the Right is still underrepresented in the fight against the hawkish dead consensus and the GOP’s governing class lags well behind.

There is a progressive critique of U.S. foreign policy that is gaining adherents, even if the Democratic Party nominated a conventional liberal hawk to challenge Donald Trump for president of the United States. Joe Biden represents the death rattle of the fading New Democrat politics of the 1990s, with its ever-present fear of being seen as less ready to go to war than the Republicans, a cry of electoral desperation and a reluctance to go into a competitive general election with an overtly socialist standard-bearer. Biden is himself responsive to trends within his party, including on matters of war and peace, even if he is too likely to appoint to critical national security positions the same set of officials who ruined Barack Obama’s foreign policy. Bernie Sanders’s team of relative realists is more likely to be the party’s future.

But there are millions of Americans for whom the progressivism of 2020 does not even claim to speak. Tulsi Gabbard’s fate—she won some delegates in American Samoa, and was kept off the debate stage as voting drew closer—shows that the modern Democratic Party prioritizes wokeness over war. Left-Right “transpartisan” coalitions can accomplish important things together, as the congressional resolution demanding an end to the war in Yemen shows. They have also become inherently unstable under Trump, who is an asset to making antiwar arguments to conservatives but anathema to liberals.

There has also been considerable resistance to the neoconservative hegemony that dominates Republican foreign policy thinking, making it possible once again to vote in good conscience for a GOP presidential candidate without the reservation that the installation of a center-right commander-in-chief will inevitably lead to a repeat of the Iraq war or worse. But much of this pushback, welcome as it is, comes from libertarians. The American political coalition that is more skeptical of statism, and has been since at least Ronald Reagan if not Barry Goldwater, needs to be reminded that war is as likely to end in failure or produce unintended consequences as any other government program. Too often, Republicans treat the Pentagon as an honorary member of the private sector and exempt its endeavors from the scrutiny they would apply to bureaucrats of any other stripe. But federal employees actually do a better job of delivering the mail than delivering democracy to the Middle East.

Libertarians have done yeoman’s work in turning the neocon foreign policy monologue of the 2000s into a real dialogue. Especially invaluable has been the contributions of two families, the Pauls and the Koch brothers. When the history of early 21st century conservatism is written, their names will be at least as important as the Kristols and Podhoretzs. But at the present time, libertarianism does not appear to be a governing philosophy that can win a national election and therefore seriously contest for control of U.S. foreign policy. The younger generation of conservatives who reject interventionism run amok should not be forced to choose between prudence in immigraton policy or foreign affairs, an endless repetition of a Reagan economic program better suited to the 1980s than 2021, or going abroad in search of monsters to destroy in pursuit of imaginary WMD and equally fictitious democratist fantasies, based on ideas that were terrible then and now, this time covered in a veneer of focus-grouped populism.

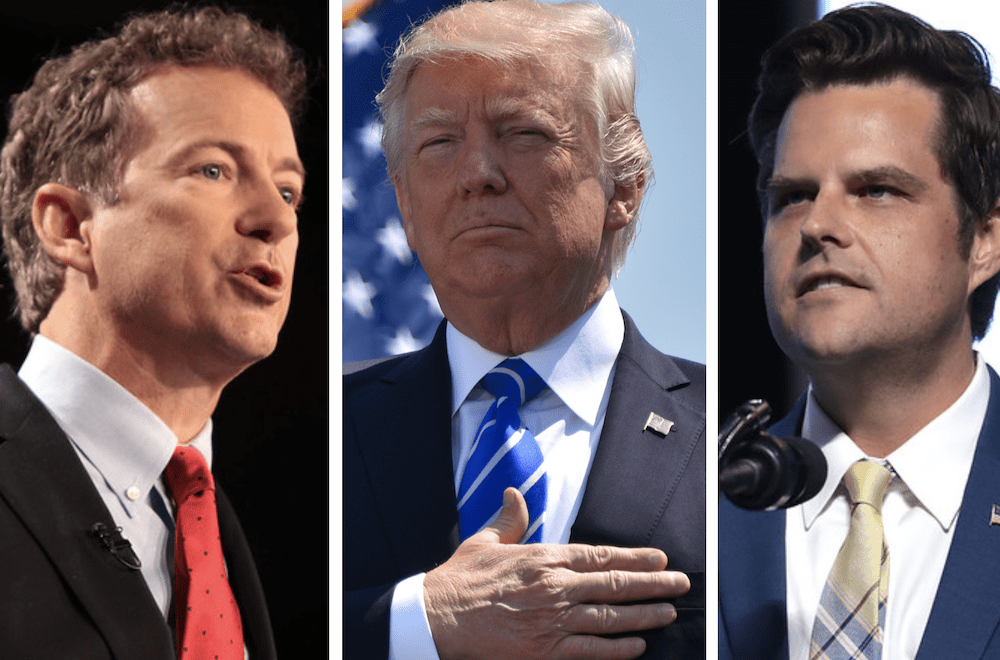

Yet the new national conservatism has produced exactly one reliable populist Republican politician who has shown a willingness to vote according to Trump’s foreign policy campaign promises when the going gets tough: Rep. Matt Gaetz of Florida. The foreign policy of Sen. Josh Hawley remains a work in progress, though a potentially promising one; Sens. Tom Cotton and Marco Rubio remain as hawkish as ever, however Trumpian they have become on other issues. Rep. Walter Jones, who arrived at antiwar conservatism from a non-libertarian starting point, is dead. Rep. Jimmy Duncan is retired. This is a smaller group than the handful of libertarian Republicans standing athwart the neocon war machine yelling stop.

♦♦♦

Trump himself bears a great deal of responsibility for this unmet challenge. He has largely delivered the foreign policy of second-term George W. Bush, an improvement only over the first-term variety, though he seems a great deal less pleased about it. He has cycled through defense secretaries and national security advisors, but the endless wars have not yet come to an end. The most important former Trump official and ally who has moved in the right direction on foreign policy is Jeff Sessions; the president is actively campaigning against his return to the Senate. He has not started any new wars, but he has risked escalating some old ones—and, most dangerously, fanned the flames of tension with Iran.

That doesn’t mean Trump’s better instincts on foreign policy have been meaningless. Without them, the Qasem Soleimani killing earlier this year could have easily metastasized into a full-fledged Iraq-style war with Iran. He would not have sacked John Bolton, whom he should never have hired in the first place. He has kept the debate over the U.S. presence in Afghanistan and Syria from fading into the background as falling bombs become ambient noise. He has eroded ISIS’s gains without massive new deployments to the Middle East and has stopped short of fighting every side of the Syrian civil war. Trump has also laid bare many of the leftist assumptions that undergird contemporary neoconservatism and sent prominent neocons, whose muggings by reality had apparently worn off, back to their ancestral homes in the Democratic Party.

What Trump hasn’t done is implement a new foreign policy that differs sufficiently from that which gave us the tragedies of Iraq and Libya or create a new talent pool of qualified federal officials who could help a future Republican president do so. With the possible exception of Gaetz, he has not even put the Republicans most aligned with his preferred foreign policy in the best position to succeed him. What does it profit us to move some troops around in northern Syria only to wind up at war in Iran, or to lose Jennifer Rubin as an intermittently conservative blogger at the Washington Post only to gain a President Nikki Haley?

Trump’s biggest positive contribution, like that of TAC founding editor Pat Buchanan before him, is to demonstrate that there is a real constituency for a different policy within the Republican electorate. To be sure, some of it had to do with their credibility with grassroots conservatives and GOP-aligned demographics. It was difficult to caricature Trump or Buchanan, like Jim Webb across the aisle, as uninterested in American national security or interests. They were not, hysteria about Russia or Iraq notwithstanding, “unpatriotic conservatives” in the eyes of rank-and-file Republicans. They were seen as unimpeachably pro-American.

As antiwar conservative Fox News host Tucker Carlson explained it in another context, the American people do care if the president keeps them safe. “You can regularly say embarrassing things on television,” he said. “You can hire Omarosa to work at the White House. All of that will be forgiven if you protect your people. But if you don’t protect them—or, worse, if you seem like you can’t be bothered to protect them—then you’re done. It’s over. People will not forgive weakness.” Trump in 2016, like Buchanan in 1996, passed that test in Republicans’ eyes in a way that a liberal George McGovern and most libertarians never could. Ergo Trump sits in the Oval Office while McGovern lost 49 states and the Libertarian Party has never won more than 3.3 percent of the national popular vote.

But it wasn’t just the messenger. The message was a fundamentally conservative one, even if not the stereotypical saber-rattling Republican argumentation. The United States is a great country, but not an embryonic United Nations. We have values, but also interests that should guide our foreign policy. “We can’t be the policeman of the world” was an actual statement of fact, not a disclaimer before intervening militarily in a half dozen or so countries. We are a republic, not an empire. The republic was established by our Founding Fathers, the empire is of more recent—and not necessarily conservative—vintage. The arguments for presidential warmaking with minimal congressional involvement, a straightforward violation of the Constitution, were believed by few Americans before the 1940s, few Republicans before Richard Nixon was president, and few conservatives before Reagan. That makes them fairly difficult to square with originalism.

Conservatives pride themselves on a realistic understanding of human nature. We know that culture and history matter. We appreciate when the use of force is appropriate to solving problems and when it is jamming a square peg into a round hole. We are skeptical of social engineering, especially when the engineer’s knowledge of his subjects is purely abstract and academic, untethered from any real-world experience. For all of the above reasons, conservatives should reject nation-building of the kind the United States has repeatedly embarked upon over the past two decades, usually in contravention of Republican campaign promises.

The United States can and must fight enemies who would do Americans harm, based on a real as opposed to a highly speculative definition of that phrase. We can vanquish any military foe. Conservatives are not pacifists. But we cannot erase the realities of culture and history, superimpose our system on other peoples as if it comes out of a box with an easily accessible instruction manual attached to it. We can make terrorists who would attack us pay a heavy price for doing so. We cannot make them be just like us, and we cannot prevent them from existing in the first place.

Except, that is, by recognizing that people living in other lands will react to our military action the way we would theirs. The bombing of Afghan wedding parties, however accidental, does not produce converts to American-style liberal democracy. Errant drone strikes do not win hearts and minds. Just as an extremely partisan Democrat begins to tell pollsters she approves of Bush’s job performance when the Twin Towers are toppled, people abroad rally to their regimes and the flag when foreign missiles start flying—even regimes they rightly hate when the missiles are marked made in the USA.

Virtually all of the interventions we have undertaken since 9/11 have eventually left the forces that most closely resemble those who attacked us stronger. Libya and Iraq teemed with ISIS fighters. Sometimes we arm jihadists directly, in search of pro-Western moderates who turn out to be as elusive as Iraqi WMD. Sometimes they gain power amid the chaos that follows poorly planned regime change. Sometimes they get American munitions simply through bureaucratic oversight. We initiate wars saying we will protect Americans from foreigners, only to spend more than a decade protecting these same foreigners from each other, refereeing civil wars between factions we barely understand.

“It all began with the dangerous idea that we could make Western democracies out of countries that had no experience or interest in becoming a Western democracy,” Trump said during his 2016 speech at the Center for the National Interest. “We tore up what institutions they had and then were surprised at what we unleashed. Civil war, religious fanaticism; thousands of American lives, and many trillions of dollars, were lost as a result.”

What that should have taught us, but didn’t, was that our power is vast but not limitless. Our interests are not infinite. Our probability of success in missions that require us to remake societies in our own image is low even if we are militarily superior by any conventional measure. Instead our approach to a place like Afghanistan is akin to the coronavirus quarantines: we must keep Kabul locked down first to keep the local forces from being overwhelmed and then eventually until a vaccine for jihadist ideologies is discovered. Fifteen days to flatten the curve, 20 years to flatten the Taliban.

Conservatives since Reagan have been fond of the phrase “peace through strength.” But the opposite is also true: we can sometimes gain strength through peace. Not every projection of force enhances American strength. Some sap it. Even for the world’s sole surviving superpower, resources that are spent in Afghanistan or Iraq are not available to meet future challenges. Much of official Washington fails to understand this, but Trump does. “We’re rebuilding other countries while weakening our own,” he has said. “In the Middle East we’ve spent, as of four weeks ago, $6 trillion. Think of it,” Trump told the Conservative Political Action Conference during his first year in office. “And, by the way, the Middle East is in what—I mean, it’s not even close—it’s in much worse shape than it was 15 years ago. If our presidents would have gone to the beach for 15 years, we would be in much better shape than we are right now.”

Trump’s emphasis on American interests and the costs of interventionism to the U.S. makes it possible for him to reach conservatives who might otherwise have a closed mind to arguments about foreign policy restraint. Hawks have an advantage in being able to hit certain emotional buttons when advocating for conflict, while skeptics like Ron Paul and those on the antiwar Left tend to focus on the immorality of America’s treatment of foreigners. There is considerable merit to these arguments, of course, and they even have a conservative pedigree. Henry Regnery published They Are Human Too about the plight of the Palestinians; the Old Right questioned using the atomic bomb on Japan. But that is not where most conservatives are today.

Political and messaging advantages aside, Trump does err too on the side of an American-centric view. “Let’s not invade Iraq, but if we do let’s steal their oil” is a significant departure from the Christian just war tradition, which ought to inform any civilized conservatism. This belligerence also leads to his departures from realism and occasional descent into warmongering. But the America First style can be employed by nimbler hands. New York Times columnist Ross Douthat once observed that what Rand Paul “seems to understand is that the Republican base doesn’t really have a detailed set of foreign policy positions: What it has, instead, is the cluster of sympathies and instincts (pro-Israel, pro-military, nationalist rather than globalist, fretful about radical Islam, skeptical of international institutions) that Walter Russell Mead has famously dubbed ‘Jacksonianism,’ which can incline G.O.P. voters for or against different policy choices depending on how those options are presented.” What Trump lacks in delivering a coherent Republican alternative to neoconservatism he at least partially makes up for by presenting politically viable arguments for one that could be taken up by a more principled, or even just a more disciplined, future GOP leader.

♦♦♦

What might that conservative alternative look like? It would start with the realization that the United States is a big, powerful country with two oceans on either side. We should make our commitments and decisions from a position of safety and security, not fear. Viewed through that prism, most of our enemies look small. Our interests in Iraq are peripheral. Iran is mainly capable of killing Americans because we still have so many stationed next door. Whatever Vladimir Putin’s ambitions, Russia remains economically weak and in demographic decline. It is but a shadow of the Soviet Union, which we defeated in the Cold War.

George W. Bush was emphatically wrong. “The survival of liberty in our land increasingly depends on the success of liberty in other lands,” he said in his second inaugural address. “The best hope for peace in our world is the expansion of freedom in all the world. America’s vital interests and our deepest beliefs are now one.” That has never been true. It is not conservatism, but a kind of radicalism. Governing as if it were true has led to war, tragedy, and anarchy rather than freedom. We do not have the authority to expand freedom in all the world nor do we know how, though we can heed John Quincy Adams and be its well-wisher. We do know how to guard our own borders, which the Bush administration emphatically did not do until relatively late in the second term.

An unrealistic foreign policy can never be a moral foreign policy. Whatever values we claim to be advancing, if we shed blood and treasure without being able to actualize them we have not advanced some noble purpose. If we make promises to the Kurds, South Koreans, the Senkaku Islands, or some new NATO expansion state that we cannot and should not keep, we are not taking a bold stand for human rights or against tyranny. Motives matter, but the morality of our foreign policy cannot be judged by our intentions. If the goal is to help Muslim girls attend school but the result is the destruction and displacement of Middle East Christians, it is a failure. Preventive war cannot satisfy the criteria of just war theory.

The United States’ primary interest in the Middle East is not solving its religious wars, creating democracy, or even oil at this point. It is preventing terrorism. But that does not require the permanent occupation of Afghanistan or any other country. We can shrink our military footprint in the region while enhancing our intelligence, surveillance, and strike capabilities. The reluctance to take out known terror targets that existed prior to 9/11 is no longer in evidence. We should get out of Iraq, where we defend a government that claims it does not want us to be there, before we end up at war with Iran. We need to invest in defense capabilities against the threats that really exist, not waste resources with lengthy occupations of foreign countries.

China is our greatest challenge. A war with Beijing would be a strategic disaster and an unparalleled humanitarian catastrophe. Even a Cold War 2.0 should be mightily avoided. But China is a hostile regime with actual power. It offers a rival model of governance to the United States. It has discovered that the selective existence of markets can be used to enrich and empower a ruling party that still calls itself communist. And we are economically entangled with China, without any obvious liberalizing effect on their system while they demonstrate new capabilities to influence ours. The woke capitalist will sell the Chinese communist the rope that will be used to hang him. Some decoupling is in order—free market champions did not argue during the Cold War that capitalism required dependence on the Soviets.

Cold War that capitalism required dependence on the Soviets.

What is true of the United States is true also of enemies and rivals. Overreach can make a country economically and militarily weaker. The proper historical analogy is not always Poland and Nazi Germany in the late 1930s, but sometimes the Soviets in Afghanistan in the late 1980s. China may also be acquiring too many enemies for its own good, having stayed out of the equivalent to America’s Middle East adventures.

Trump has shown that conservatives aren’t necessarily eager to go to war, even if they remain entirely too trusting of Republican presidents who want to take them there—including the current occupant of the Oval Office under the wrong set of circumstances. That is a good first step, but it is far from sufficient. Conservative restrainers must stop being passive observers in a foreign policy debate Trump and their libertarian allies have already joined. It’s well past time for a conservative foreign policy of peace.

W. James Antle III is politics editor of the Washington Examiner.

Comments