There’s No Real Definition of ‘Conservatism’ and That’s a Good Thing

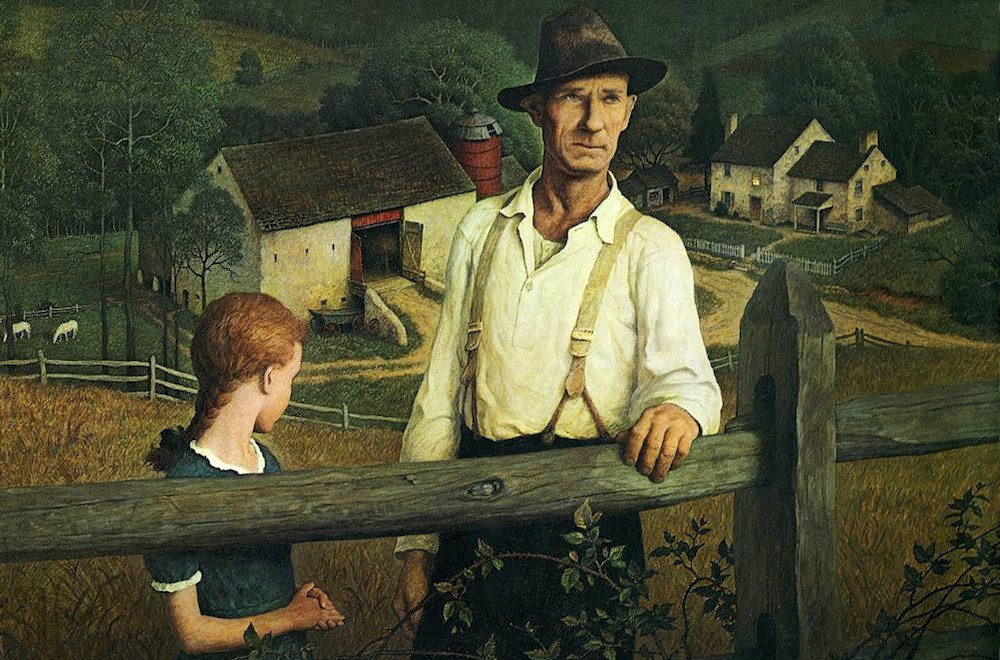

When the prestigious publishing house Holt, Rinehart, and Winston published “What Is Conservatism?” edited by Frank Meyer, on March 6, 1964, there was an air of triumph to the entire drift of those not firmly on the ideological Left.

The movement itself was just celebrating a little over a decade of success, following upon Russell Kirk’s magisterial The Conservative Mind (Regnery), Leo Strauss’s insightful Natural Right and History (University of Chicago Press), Ray Bradbury’s poetic dystopia, Fahrenheit 451 (Ballantine Books), and Robert Nisbet’s penetrating The Quest for Community (Oxford University Press) in 1953. William F. Buckley Jr.’s National Review had been making cultural inroads since late 1955, Young Americans for Freedom had swept across American college campuses in just four years, and a young, dashing, and forthright senator from Arizona was the knight errant of millions of Americans.

Whatever fate Goldwater would suffer in the November elections, his was a moment that was not fated to be “has been.” Besides, What Is Conservatism? came out in March, and the November elections were still eight months away. Success, then, should have been within the grasp of American conservatives, if not in the White House, at least, in some American universities and in some cultural institutions. Right?

1964’s What Is Conservatism?—featuring pieces by Kirk, Buckley, Meyer, Friedrich Hayek, Father Stanley Perry, Wilmoore Kendall, John Chamberlain, Gary Wills, Wilhelm Roepke, Frank Chodorov, and a whole host of others—served as a “Who’s Who” of the movement, in all of its glories and in all of its failures. Its main glory was that it proved that conservatism mattered. Its main failure was that no one could agree upon what conservatism actually meant or how one would define it in a way that brought together so many diverse thinkers and their own particular ideas. As such, What Is Conservatism? is witty, encyclopedic, captivating, prickly, interesting, triumphal, broad, narrow, painful, joyful, and self-effacing, all at once.

Then as now, the conservative served as not only the world’s best critic, but also as a critic concerned with his own place within criticism itself. And, like all conservatives, past and present, these conservative writers were profoundly idiosyncratic and individualist, even as they lamented individualism.

The reviewer for The New York Times was not incorrect when he explained in his review of What Is Conservatism?, “One is all but obliged to conclude that although there are many highly intelligent American conservatives, there is as yet no formulated American conservatism.” In general, two things should hold conservatives together, the reviewer continued, what to conserve of the past and what to fear in the present. Sadly, the New York Times reviewer concluded, most “new conservatives,” as they were then called, only spewed forth their bitternesses about what they hated. This seemed to be all they could agree upon.

Jump now to the time of Corona, in the year of our Lord 2020. “Conservative is kind of a meaningless word now,” a young and skilled writer (one I like to read, Brad Polumbo) recently stated on social media. Meanwhile, over at the venerable Intercollegiate Studies Institute, an institution charged with promoting conservatism within higher education, another young and gifted writer, Gracy Olmstead, writes: “I am loath, in fact, to embrace the label ‘conservative’ myself—in part because of the ways most people define it, and in part because I am unsure whether any political label fully defines my beliefs.”

I suppose it must be age and, perhaps to some extent, ego, but I find such statements to be as mystifying as they are unsatisfying. While I agree that conservatism is not, nor ever should be, a political label, I am far less certain that it should be loathed or dismissed so readily. I also fear that in this age of Trumpian populism and soft authoritarianism, conservatism is all too readily confused with populism.

The most important question for any conservative remains: what should be conserved?

When Russell Kirk, the father of post-World War II conservatism, attempted to explain the meaning of the movement, he counseled against any ironclad definitions. Taking a term from the tradition of the Roman Catholic Church (of which he was not yet a member in 1953), Kirk argued that one should define conservatism in terms of “canons” or tenets, rather than in terms of absolutes. In some writings, he offered four canons, in some five canons, and in some ten canons as he struggled with the meaning of conservatism. Most often, though, Kirk listed six.

One: a conviction that one God—most likely, for Kirk, the Stoic Logos in 1953, but the Trinitarian God of orthodox Christianity by 1964—rules over all things, transcends all things, and holds all things together. If we rely merely on the human understanding of reason, he continued, we end with the Cross, with the administering of hemlock, and with the naming of false goddesses. In essence, the Logos defines the universal.

Two: a love of the particular as a specific manifestation of the universal. In this, Kirk wrote, we should embrace an “affection for the proliferating variety and mystery of traditional life, as distinguished from the narrowing uniformity and equalitarianism and utilitarian aims of most radical systems.” Each person, then, is a unique and unrepeatable reflection of the Logos and must be treated as such.

Three: that society demands variation in rank, class, and structure. Fearing radical egalitarianism, the conservative must uphold the excellence within each person and within each community, recognizing that thing of excellence as a leavening agent for the rest of the community and its members.

Four: that of all natural rights, the most important is property. If one does not own himself and take responsibility for his moral actions, he can never be expected to lead or even to live with another. Each person, in Kirk’s view, is a moral agent, a manifestation of free will itself. Kirk also meant ownership of land and “stuff,” but he mostly meant being morally and ethically culpable.

Five: a belief that tradition is the accumulated experience of humankind and, thus, the only real and efficacious laboratory of sociology that has ever existed. In this, the conservative recognizes the power of reason, but also its limitations. When combined with the first and second canons, one might state—with Plato, Cicero, and C.S. Lewis—that there is eternal reason (Logos), private reason (rationality), and the reasonableness of experience.

Six: a “recognition that change and reform are not identical, and that innovation is a devouring conflagration more often than it is a torch of progress.” Here, Kirk is rather directly channeling Burke as he acknowledges that each generation may act in three different ways when inheriting the past. It may reject the inheritance, accept the inheritance, or reform the inheritance. Kirk, as did Burke, favored the latter course as it demanded that each generation see itself in continuity with all other generations, past and future.

Kirk wisely chose to define conservatism by not defining it. He was, however, fundamentally clear that conservatism did not belong exclusively to the sphere of politics. It was a movement in education, in literature, in the arts, in living, in religion, in economics, and in politics. But never in politics alone.

When the critics of conservatism emerge—whether in 1964 or 2020—they all too readily view conservatism as primarily a political movement, and, more often than not, as a populist movement. Yet, the difference between conservatism and populism is not only vast, but it is also insurmountable. At its root, populism seeks homogeneity throughout culture, while conservatism embraces variety and distinction.

By its very nature as well as by its own history, conservatism can never be a coherent ideology, centered around a like-minded group of (un)thinkers, dedicated to remaking the future of government or of political society. Backward looking, conservatism was born as a rebellion against conformity in society, in bureaucracy, in education, and in government, and, by its very essence, it promotes what is eternally (not temporarily) true, good, and beautiful. It seeks that which is everlasting even as it finds such everlasting things in mortal envelopes, slowly crushed by time.

Is there an American conservatism? Yes…and, no. Harry Jaffa once stated that all American conservatism must be defined by its relationship to the American founding. He was certainly correct about this. The Judeo-Christian and Greco-Roman traditions as understood through the experience of Anglo-Saxon common law anchor our conservatism in the United States. We must never fail to ask, just what are we conserving? What matters most is how our traditions uphold (or not) the dignity and uniqueness of the human person. If our conservatism conserves that which is evil, false, and ugly, it is a failure, lower than mere misery. If such were the case, I’d be loath to embrace it as well.

Is there an American conservatism? No…and, yes. To understand it, though, one must be willing to sift through thousands of events and thousands (plus) of traditions and an innumerable number of decisions made by unique individuals, each endowed by their creator with free will.

Yet, in 1964 when What Is Conservatism? appeared, it was thoughtful, intense, and diverse. It remains so in 2020…at least for those with eyes to see and souls to imagine.

Bradley J. Birzer is The American Conservative’s scholar-at-large. He also holds the Russell Amos Kirk Chair in History at Hillsdale College.

Related: Introducing the TAC Symposium: What Is American Conservatism?

See all the articles published in the symposium, here.

Comments