The Secret Plan to Revive the American Right

Sorry about that headline. It seems to be a fact of contemporary discourse that readers are more likely to click on something if they believe it to be purloined. If this communication had arrived on, say, the embossed stationery of Kevin McCarthy, you might well have passed it by. We scribblers must adapt.

No disrespect to Congressman McCarthy, but appeals to authority no longer appeal because they no longer stand on a foundation of general esteem. The institutions that underpin respectable opinion—the fashionable media, the permanent government, the well-placed if not always well-versed experts—all show signs of dry rot and inspire not confidence but head-jerk skepticism.

We do no better with appeals to authenticity. Take the Democratic nomination contest now fissiparating. The reason that Beto has a puncher’s chance against Bernie is the widespread suspicion that, deep down, Bernie really believes all that socialist horseradish. Why would you honeymoon in the Soviet Union unless you believed that you were showing your bride the future of the world, and that she, too, might become ideologically aroused? As for Beto, well, as they say in the faux-Hispanic community, no way, Jose. Beto looks the part of a man on a mission—all tousled RFK hair, tight jeans and large, certifiably clean teeth—but we all know that, in his case, the missionary has no mission. On available evidence, he may not even have a moral core, only an extra gland that time-releases steady doses of self-enchantment. Inconveniently for Bernie, who, poor man, seems to have been chronically inconvenienced by history, Beto is the real deal, a veritable monument to inauthenticity. In the grand tradition of Barack Obama, you might say.

So here we are. No authority. No authenticity. Not even an identifiable center, vital or otherwise, with both ends of the political spectrum having pitched forward into the name-calling stage of philosophical exhaustion. The tabula is rasa.

This might be an opportunity.

In political terms, Donald Trump is a tidy fellow. When he exits the stage, he will leave behind him no movement and will take with him only the famously skeletal “Trump organization.” He will be remembered more for an aura than a legacy: his appeal has never been ideological but attitudinal and is thus non-transferable. (Who knew that there were tens of millions of voters in 2016 so riled that they could be moved to give them the digital salute? You know, them. The power-tipsy bureaucrats, the globalist toffs, the faith shamers, the financial deck-shufflers, the culture arsonists, the lifestyling aborters. Them.) At the end of the Trump run, there will be left standing only a single Trump Republican outside the immediate family. And if he can grin and bear it for another six years, Mike Pence could be that man. The guesstimate here is that, off at the end, he won’t be. The working assumption is that the handoff would work only if Trump could say credibly to Pence, as Reagan said to Bush 41, “I never could have done it without you.” Trump won’t be able to say that. He thinks he could have done it with Steve Doocy.

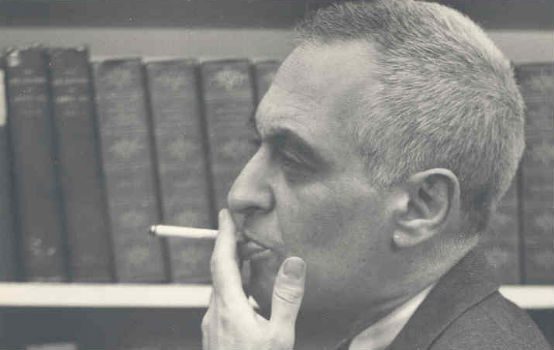

Ten years ago, I was convinced that what conservatives needed most was another Ronald Reagan—a political leader with the charismatic power to revive and inspirit our movement. Three years ago, after Trump had busted up the old paradigms, I became convinced that what we needed was another William F. Buckley Jr.—a man who could re-weave the tangled strands of our coalitional fabric into a more-or-less coherent political platform. I am now convinced that what we need is another Frank Meyer: a man who can do the hard doctrinal work to fashion a new governing coalition for a new political circumstance.

Meyer, a man seized frequently by libertarian impulse, was able to club two of his more unclubbable colleagues—the majoritarian Willmoore Kendall and the traditionalist Brent Bozell—into joining the fusionist enterprise. It was an historically successful collaboration and produced, ultimately, a governing conservative majority.

Frank Meyers, alas, don’t grow on trees. He was a formidable intellect, one of those rare autodidacts who hold degrees from Princeton and Oxford. He was a skilled practitioner of the political arts: he had a knack for getting to 51 percent in constituencies stretching from county-wide to continental. And he had the leaden bottom of a born mediator. He could sit and smoke and talk and drink and noodge longer than you could. In most of the dialectical contentions of the early movement, he prevailed.

If you spot another Frank Meyer, don’t keep the news to yourself. But in the interim, the Remnant should sharpen the basic tool of coalition building.

We should repristinate the politics of reality.

How might we do so? Well, we could begin by leaving the storm-chasing of the Twitterverse to others. As I write these words, Washington is aflame with reports and rumors (a distinction all but disappearing from the major media) about which candidate should fill a mid-management post in one of the mid-range Cabinet departments. Frank Meyer would doubtless have had a candidate for the vacancy—he was, de facto, the personnel director for the vast right-wing conspiracy—but he wouldn’t have wasted a minute campaigning for him.

Instead, he would have identified our large and potentially existential challenges and begun immediately to develop responses both principled and prudential. Two examples leap to mind. First, the epochal threat posed by Chinese ambition. I’m not talking about economics here. I have no confident opinion as to whether the Chinese economy will grow to the sky or deflate like a Japanese balloon or plateau somewhere in between. I cannot even predict whether Chinese bellicosity would be more likely to become inflamed by prosperity or by deprivation.

What I do know is that, in the estimate of sober defense analysts, the military realities have changed. When a decade ago the Chinese defense buildup began in earnest—with serious money, regional deployments, and surprisingly good hardware—the Chinese advance alarmed only the professional alarmists. (Think tankers have to make a living, too.) Most mainstream analysts thought the Chinese were doing no more than what any emerging power would do under favorable economic conditions: they were building the capability to defend their homeland against potentially aggressive neighbors. That’s what responsible sovereign nations do, the analysts assured us.

Developments on the ground have now outrun that analysis. Beijing’s military machine can no longer be described as defensive in nature. It is no longer configured solely to deter attack from India, say, or Japan. The Chinese are racing to project an offensive capability and the question is, as it always is in pivotal moments of history—against whom? In the absence of a readily acceptable alternative, the prudent answer would seem to be—against the incumbent military power in the western Pacific.

The other imminent and potentially existential challenge is the debt bubble, by which I mean government debt for which there is no reasonable prospect of repayment. The problem at the federal level is best described by Mitch Daniels (as has been his annoying habit for many years). Daniels notes that until a few years ago—call it mid-Obama—there were paths to entitlement reform that might have assured older Americans that commitments to them would be honored. That is no longer arithmetically possible. When the bubble bursts, or even when it begins to leak steadily, the elderly will not get what they’ve been told is coming to them. If you can think of a development that would more dramatically erode trust in democratic governance, you have a vivid imagination.

The problem is even worse at the state level. Despite the revenue windfalls from full employment and up-market investment returns, many states are struggling with underfunded pension systems. Until a full-blown crisis gives them cover, state officials believe they can’t tax enough or grow returns enough or cut benefits enough to restore stability. In some blue states, the situation is already dire. I count at least three states—New Jersey, Illinois, and Connecticut—where officials are actively considering “asset transfers” to soak up funding liabilities. That’s pretty much what it sounds like.

Faced with the prospect of asking public employees to take a haircut, blue states are instead proposing to donate bridges, tunnels, and airports to support union pension payouts. The proposals, in a nutshell, are to give away our furniture to pay their rent. Everybody on board with that?

Wish you were here, Frank.

Neal B. Freeman covers American politics from Florida.

Comments