‘The Longer Telegram’ Is a Recipe for Costly Failure

An anonymous former government official has written a conventionally hawkish paper on China. The Atlantic Council and Politico have both published versions of the piece, and they have agreed to keep the author’s identity under wraps for reasons known only to them. The Atlantic Council claims that anonymity was necessary because of “the extraordinary significance of the author’s insights and recommendations.” It’s not clear why they find these insights and recommendations to be so extraordinary, since almost everything in the paper has been said before by various authors. It makes no sense why the author would need to remain anonymous in order to make these views known. The author likens the paper to George Kennan’s “Long Telegram” by calling it “the longer telegram,” but the paper has little or none of Kennan’s astute observations about history and strategy. A lot of it is a series of regurgitated ideological claims about the Chinese government and its ambitions under the leadership of Xi Jinping. In that respect, it is not so different from H.R. McMaster’s attempt from last year. It is just much, much longer.

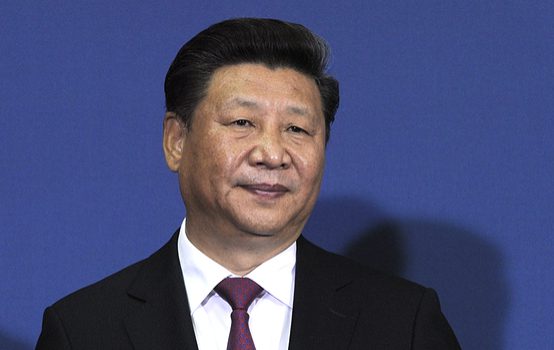

It may come as a surprise to learn that “Xi has returned China to classical Marxism-Leninism,” but this is what the executive summary of the report says. That is a bizarre and incorrect claim, but it is one that the anonymous author returns to several times. The author asserts that “Xi has demonstrated that he intends to project China’s authoritarian system, coercive foreign policy, and military presence well beyond his country’s own borders to the world at large,” but we are left wondering how this has been demonstrated and he never proves his case. Then the author oversimplifies things quite a bit when he says, “China under Xi, unlike under Deng Xiaoping, Jiang Zemin, and Hu Jintao, is no longer a status quo power. It has become a revisionist power.” Even granting that China has become somewhat more combative over certain territorial claims in the last nine years, this overstates the case. China can sometimes behave like a revisionist power, but in many ways China benefits from the existing institutions and rules and doesn’t wish to overturn them. It is inaccurate to describe China as being simply revisionist, and it creates a very misleading picture of China’s strategic goals. In short, the anonymous author exaggerates Chinese ambitions and threats as many China hawks tend to do, and he casts the rivalry between the U.S. and China in stark ideological terms that do not reflect reality.

One unique element in the essay is the author’s proposal that the U.S. focus its attention on Xi and the party elite:

Given the reality that today’s China is a state in which Xi has centralized nearly all decision-making power in his own hands, and used that power to substantially alter China’s political, economic, and foreign-policy trajectory, US strategy must remain laser focused on Xi, his inner circle, and the Chinese political context in which they rule. Changing their decision-making will require understanding, operating within, and changing their political and strategic paradigm. All US policy aimed at altering China’s behavior should revolve around this fact, or it is likely to prove ineffectual.

Right here we can see the critical flaw in the author’s proposed strategy that renders the rest of the essay rather redundant. He imagines that there is some way that the U.S. can successfully change the decision-making of top Chinese officials when our government’s record of compelling foreign leaders to change their behavior is very poor. The U.S. has tried and failed to force changes in regime behavior in much smaller, weaker countries than China. The idea that the U.S. has the ability to force such changes in the Chinese government’s behavior is sheer fantasy.

If the U.S. is supposed to change Chinese officials’ decision-making, what does the author want to achieve? The author says that the “overriding political objective should be to cause China’s elite leadership to collectively conclude that it is in the country’s best interests to continue to operate within the existing US-led liberal international order rather than build a rival order,” but pressure tactics are likely to encourage China to build more parallel institutions as a way of adapting to pressure.

The author wants to convince Beijing “that it is in the party’s best interests, if it wishes to remain in power at home, not to attempt to expand China’s borders or export its political model beyond China’s shores.” In addition to being a reckless threat of attempting regime change if they do not comply with U.S. wishes, this is a solution to a problem that largely doesn’t exist. Chinese territorial ambitions are limited, and its government has no desire to export its political model anywhere outside its own territory. Like Pompeo and McMaster, the anonymous author assumes that China has ideologically-driven expansionist goals that encompass the globe. He is on guard against a phantom menace.

The paper embeds the author’s misguided China recommendations in a defense of continued U.S. global primacy. There are all the usual salutes to the virtues of U.S. “leadership” that we have come to expect from such arguments: “US leadership remains the only credible foundation for sustaining, enhancing, and, where necessary, creatively reinventing the liberal international order.” The paper declares that America’s “core objective must be the retention of US global and regional strategic primacy for the century ahead.” This mistakenly assumes that it is both possible and desirable to sustain U.S. primacy in the world and in East Asia. The truth is that the U.S. has to adapt to a world in which it does not dominate East Asia or the world. The author’s unwillingness to contemplate the reality that it already upon us confirms that he is more ideologue than careful strategist.

The author warns, “To abandon this mission would mean “the city upon a hill” would fade from view as the United States became just another nation-state in narrow pursuit of its national self-interest.” This is unvarnished American exceptionalist hogwash. The idea that America might become a normal country that pursues its own interests horrifies the author. All of the threat inflation and exaggerations of Chinese ambitions serve the purpose of giving America another grand ideological quest so that it doesn’t become “just another nation-state,” but the pursuit of yet another open-ended crusade has nothing to do with U.S. security and prosperity and it will undermine and possibly even wreck both. The so-called “longer telegram” is a recipe for costly failure, and it should be dismissed as such. There is a better U.S. strategy for East Asia available, and it looks nothing like this.