The Debt Neocons Owe to the Atheist Left

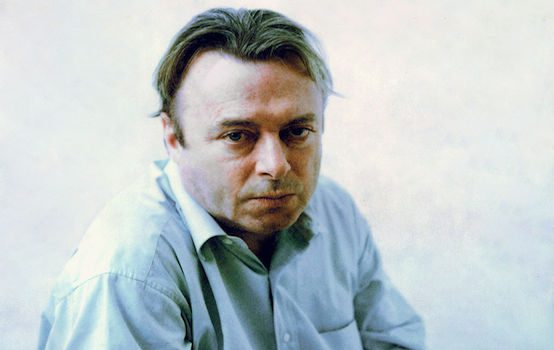

Almost exactly one year before his death in 2011, Christopher Hitchens reaffirmed his support for the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq and predicted that a “confrontation” with “theocratic Iran” was all but inevitable.

Now, nine years later, his prediction is perilously close to coming true. But if we recognize the biases that underlie the famous atheist’s assessment of the geopolitical situation, it quickly becomes clear that his hawkish worldview could never lead to peace and is in fact a recipe for perpetual, and perpetually escalating, war.

When I recently watched Hitchens’ 2009 debate with Christian apologist William Lane Craig over the existence of God, I noted that although Hitchens’ logos failed to measure up to Craig’s philosophical expertise, on the level of pathos, Hitchens’s stark recounting of the horrors of religious violence and oppression could not be easily discounted, even by a lifelong Christian like myself.

Eventually, though, Hitchens began to overplay his hand, blaming Russian ultranationalism and the continuing cult of Stalin on the Orthodox Church and the Holocaust on Christian anti-Semitism without so much as gesturing toward either the Soviet Union’s religious persecutions or the eugenics movement that was vehemently, and almost exclusively, opposed by such religious intellectual giants as G.K. Chesterton. Hitchens even compared North Korea’s totalitarian regime to the Christian conception of heaven, failing to acknowledge either the explicit atheism of juche ideology or the Christian insistence that no political leader is worthy of the reverence we owe to God.

The whole thing began to remind me of an exchange between the Catholic columnist Ross Douthat and the atheist Bill Maher on an episode of Real Time. In response to Maher’s assertion that most atrocities are motivated by religion, Douthat countered, “Not in the 20th century. Not in the Soviet Union. Lot of dead bodies there. Not a lot of Christians, except among the dead bodies.” To this day, Maher’s response still leaves me dumbfounded: “I would say that’s a secular religion.” Before Douthat could ask what the hell a secular religion is, Maher changed the subject. The meaning of Maher’s nonsensical statement was clear: everything Maher doesn’t like is religion.

Hitchens’ own atheism seems to have followed a similar trajectory. In a 2005 column on the Iraq war titled “A War to Be Proud Of,” Hitchens insisted that Francis Fukuyama’s utopian “end of history” was “over before it began” and castigates Western democracies for failing throughout the 1990s to crack down on human rights abuses in Bosnia, Rwanda, and Somalia. His clear message was that if Fukuyama’s predictions of perpetual peace in a secular, liberal, democratic world were to be realized, we must be willing to shed blood. This language of millenarian warfare is particularly ironic coming from a man who criticized Israel for encroaching on Palestinian land in an attempt (at least in Hitchens’ view) to inaugurate their own messianic age.

Christopher’s younger brother, the Anglican conservative Peter Hitchens, offered an important corrective to this atheistic utopian aggression when he wrote in his 2010 book The Rage Against God, “The only general lesson that can be drawn from these differing wars,” some overtly religious and some not, “is that man is inclined to make war on man when he thinks it will gain him power or wealth or land.” If religion is the cause of all war, then the sooner it is stamped out the better. But if violence and oppression stem from human nature rather than from superstition or clerical brainwashing, then the elder Hitchens’ commitment to attributing all the world’s ills to religious fanaticism (as defined by none other than Christopher Hitchens himself) can lead only to endless warfare against an ever-expanding list of enemies.

Eulogizing Christopher Hitchens in a 2011 New Yorker piece, author George Packer noted that his late subject’s “molten anti-clericalism…burned so hot that he turned it without a second thought at a secular, totalitarian Iraqi dictator.” Hitchens himself scoffed at the idea of describing Saddam Hussein as “secular,” but perhaps he would have regretted that assertion had he lived to see the supposedly fanatical Baath regime replaced by the truly theocratic ISIS. Or maybe not. Maybe he would have insisted that America bring the boot of secular civilization down once again, harder this time. It matters not that, as the Cato Institute’s Doug Bandow has observed, this sort of regime change “rarely yield[s] liberal, pro-Western regimes.” The floggings will continue until civilization improves.

Echoes of Hitchens’ foreign policy are still audible in the current debate surrounding Iran. When Hitchens called the Iranian government a “messianic regime” that was motivated purely by religious fanaticism and was “enslaving and ruining a formerly great civilization,” he lent his voice to the multitude of neoconservatives who insist that the Tehran regime cannot be reasoned with. If Iran’s leaders are nothing more than jabbering jihadists who have imposed themselves on the Iranian people against their will, then any war against Iran would be a war of liberation.

Peter Hitchens describes his brother’s hawkish neoconservative foreign policy as a natural outgrowth of Christopher’s youthful Bolshevism, saying that he “continued to be utopian long after he should’ve stopped, and that’s what got him into the mess over the Iraq war.” In The Rage Against God, Peter even goes so far as to claim that “utopian atheism” is “common among neoconservatives.” In light of this statement, professing Christians who agree with the elder Hitchens’ views on foreign policy would do well to question whether they also agree with his godless, leftist premises.

If humanity’s woes are entirely the result of a particular ideology (whether that ideology is capitalism or religion), then those who sustain that ideology must be exterminated. Hitchens’ foreign policy will reach its endpoint only when, to quote the 18th-century French radical Denis Diderot, “the last king is strangled with the entrails of the last priest,” with Hitchens himself deciding who falls into each of those categories.

But if human suffering is, at least in part, the result of our own inherent defects (or sins, if you like), then those who set foreign policy would do well to purge themselves of all utopian inclinations before launching any sort of military intervention. The neocon foreign policy can thus be read as an inheritance from atheistic leftism and, as Peter Hitchens reminds us, is in direct conflict with both Christianity and conservatism.

Grayson Quay is a freelance writer and M.A. at Georgetown University.

Comments