The Anti-Respectability Politics of Philip Roth

Philip Roth, perhaps the last of the greats of American postwar literature (or at least, as more than one obit has noted, the last of the Great White Males), passed away this week, yet his works promise to haunt us for a long time to come.

From the earliest days of his career, Roth courted plenty of controversy, which (like his Protestant equivalent John Updike) accompanied the breakout era of the 1960s. As Roth’s New York Times obituary recalled, “in 1959 he won a Houghton Mifflin Fellowship to publish what became his first collection, Goodbye, Columbus. It won the National Book Award in 1960 but was denounced—in an inkling of trouble to come—by some influential rabbis…. In 1962, while appearing on a panel at Yeshiva University, Mr. Roth was so denounced, that he resolved never to write about Jews again.”

But as anyone even faintly familiar with 20th-century letters knows, Roth quickly changed his mind.

“My humiliation before the Yeshiva belligerents—indeed, the angry Jewish resistance that I aroused virtually from the start—was the luckiest break I could have had,” he later wrote. “I was branded.”

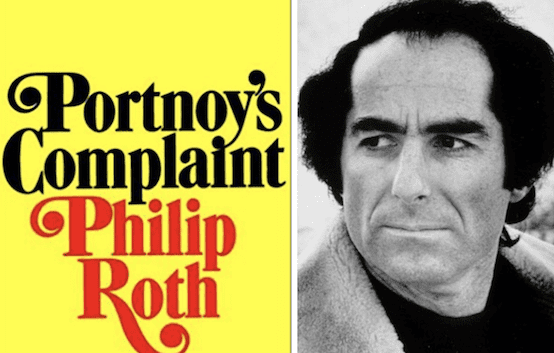

Roth increased his “brand” tenfold in 1969 with the publication of his signature novel, Portnoy’s Complaint, which told the story of Alexander Portnoy, a hypersexual, neurotic young man who has sex with just about everything in the book (including a baseball mitt and the family dinner, presaging American Pie three decades later) while going on panty raids. Portnoy became a runaway bestseller and a 1972 movie starring Richard Benjamin, as well as the talk of Manhattan and Hollywood “literary” parties. It became perhaps the biggest Jewish cultural touchstone of the 1970s outside of Woody Allen’s movies.

But many older Jews’ reactions were even angrier than the one at Yeshiva University. The legendary movie and TV producer and Broadway playwright Dore Schary called Portnoy an “outrageous” insult that “goes far beyond the good taste of a Jewish joke.” Fred Hechinger said in the New York Times that Roth must be “convinced that Jews today feel so secure in American society that nothing could ever offend them. The bathroom is no longer unmentionable. Racial and religious themes are no longer off-limits.” Author Ira Nadel said such an unflattering, even at times downright ugly portrait of Jewish maleness could lead to anti-Semites justifying themselves, as if the “criminal” were confessing at last.

This decades-old conflict at the heart of Roth’s comedic darkness gives us the clearest picture of why his writing still resonates. The American Jewish male icons of the World War II generation—Kirk Douglas, John Garfield, Sid Caesar, Jack Klugman, Walter Matthau, Duke Snider, Sandy Koufax—were every bit as tough and capable as their goyische counterparts, and were mostly accepted by Gentile society because of it. At the time, the Jewish mama’s boy—neurotic, rabbity, terrified of being thought of as gay—was regarded as akin to the Stepin Fetchit “bamboozled” minstrel or the lisping sissy as a stereotype that had to be pushed back against, not embraced.

Instead, Roth, who published books until his retirement in 2010 at age 77, aggressively dared people to confront and even re-embrace or reclaim those stereotypes. The Oscar-nominated and Emmy-winning legend Diahann Carroll told Aaron Spelling that when she talked herself into a job as Alexis’s nemesis on Dynasty, that black women wouldn’t be truly liberated in the movies or on TV until they had an unapologetic “black bitch” (her words) to watch. (Carroll had already played a perfect black woman on the groundbreaking Julia, and a complex but still admirable and lovable welfare mom in Claudine, which only underscored her point.)

The story of just about every marginalized group in the mass media has been first of either invisibility or derision (black mammies and minstrels, Norman Bates, Sebastian Venable and other “Mrs. Danvers”-style perverted/gay villains, lazy and stupid Hispanics and Native Americans, sneaky “Orientals”). Then comes the first pushback, where only Positive Role Models (which often translated to “victims” or “martyrs”) are allowed. And then the final, and arguably most important pushback: towards unapologetic, three-dimensional characters who are equally good and bad.

Roth was one of the first to paint portraits of iconic Jewish characters and wrote things about the Jewish community that no Gentile writer could have ever gotten away with without looking like the rankest anti-Semite.

It must be noted, however, that when a female writer like Jacqueline Susann wrote graphically about sex and abortion from a woman’s point of view, she was dissed and dismissed as “dirty” and “trashy.” And when an “out” homosexual like John Rechy or Gore Vidal did it, it was considered borderline pornography by many more than just religious conservatives. But when a straight white male like Roth or Updike wrote about sex—often in the most dehumanizing terms towards women characters—they were greeted with adjectives like “courageous” and “fearless” by the midcentury literary establishment.

While literary anti-heroes existed long before Philip Roth, let alone today’s “prestige TV” and Oscar-bait studio-indie films, Roth’s most famous and award-winning book besides Portnoy, the Pulitzer-winning American Pastoral, truly provides the skeleton key to the method and madness of his career. The book tells the story of “Swede” Levov, a handsome, Redford-looking, blond, Jewish jock and World War II hero who comes home to marry the nice (Catholic) beauty queen next door and take over his father’s prosperous leather goods factory in Newark, New Jersey, complete with a gentlemen’s ranch.

But the pivotal Pastoral protagonist isn’t Swede or his wife, but their not-so-merry daughter Merry (Meredith), who grows up to join the Weathermen as a bomber radical in the late 60s. From an early age, Merry knows that she will never compete with the Adonis physical perfection of her father or the “Desperate Housewives” suburban chic of her mother, having inherited Swede’s Russian ancestors’ mesomorphic, big-boned body and face, and further handicapped by a speech impediment. Andrew Hartman quite rightly called Merry the “Return of the Repressed”, which is further underlined by Swede’s hateful, jealous kid brother (a multi-married, Jewish-looking surgeon who stays proudly within Florida’s thriving Jewish community and comes across as the usual Roth stewpot of kvetching, rage-anger, and insatiable sexual frustration). The book makes it clear that Swede all but deserves everything that’s coming to him, as his radical daughter dismantles the Ward and June Cleaver life that he and his even more “assimilated” Catholic wife have carefully cultivated. “You wanted [the real] Miss America? Well you’ve got her with a vengeance!” a satisfied Brother Dearest taunts Swede. “She’s your daughter!”

While Roth wasn’t a Christian, one thinks he probably took to heart the little ditty in the Book of Revelations that talked about a person being better off “hot or cold,” and how the lukewarm would be spat out of the mouth. Swede Levov was a typical JFK Democrat (he and his wife opposed the Vietnam War, although hardly in the same manner as their flag-burning daughter)—which was the very point. It would have been too easy if Swede were a right-wing Archie Bunker or if his wife were a cold Nurse Ratched or Beth Jarrett ice queen. Pastoral is an epic and depressing morality tale that ruthlessly satirizes midcentury middle-class Great Consensus America. By not choosing sides, Mr. and Mrs. Levov’s sides have been chosen for them. (No wonder the humdrum Ewan McGregor film adaptation avoided this narrative like the plague.)

Just as shell-shocked Swede Levov died at nary 70, his first marriage ruined, the Trump/Bernie era has made plain that Merry Levov and her uncle won the war. Today, many post-Recession social media mavens are proud of their Marxism, and “socialist” is quickly becoming a Bernie-era badge of honor. Trans people proudly wear their makeup and dresses to work. College activists will tolerate anything in speech or art—except speech or art that they deem intolerant. And of course, the Fox News right is just as hardcore as ever.

While the straight-up sexism and misogyny in Roth’s books are quite rightly and correctly fated for history’s spit valve in our era of #MeToo, it is the seemingly unintentional (but really very intentional) politics and psychology of Roth’s books that will live on as a psychological X-ray of what Howard Beale in Network called “the hypocrisies of our time.” Before most Millennials or Gen Xers were even born, Philip Roth quite literally “triggered” a national literary discussion of how-far-was-too-far (and how far wasn’t enough), over sex, religion, what it means to be Jewish, and even what it means to be an American. And that’s a legacy worth remembering. RIP.

Telly Davidson is the author of a new book, Culture War: How the 90’s Made Us Who We Are Today (Like it Or Not). He has written on culture for ATTN, FrumForum, All About Jazz, FilmStew, and Guitar Player, and worked on the Emmy-nominated PBS series “Pioneers of Television.”

Comments