Summer of Love, Winter of Decline

On a sparkling 1967 June afternoon on Mount Tamalpias, I went with a college friend to the Fantasy Fair and Magic Mountain Music Festival. The Fair was a prototype for all multi-act outdoor rock and craft festivals that followed, including Woodstock. The headliners at the two-day event were Dionne Warwick, The Doors, Jefferson Airplane, The Byrds with Hugh Masekela, Captain Beefheart & the Magic Band, Tim Buckley, Every Mother’s Son, Steve Miller Blues Band, and Country Joe and the Fish.

My friend’s rowdy 17-year-old younger brother, new to me, showed up with several sinister figures in black—we would soon enough call them Manson types—acting peculiar, stoned on some powerful, unnamed drug. The next day, I got a phone call. I learned to my horror, the brother was dead. There’d been a “bad trip.” It was all very mysterious, and if the police ever asked, he said, I knew nothing. I never spoke to or saw my “friend” again.

There would be many casualties during and after the Sixties, including, finally and spectacularly, American political culture as it had been known since the Enlightenment. God and country began to dissolve, and with this, the moral axioms and civil assumptions that had ruled U.S. society since the founding of the republic. It took decades for the “regime of truth” to fade as completely as it has, but today’s social convulsions and fault lines descend from the Summer of Love.

The Summer of Love was “an invasion of centaurs,” said social critic Theodore Roszak in The Making of a Counter Culture (1969), affixing a label—counter-culture—to an exploding youth movement behaving with unprecedented licentiousness.

In May 1967 Scott MacKenzie had released “San Francisco (Be Sure to Wear Flowers in Your Hair).” An estimated 120,000 searchers and adventurers converged in the following weeks on the dilapidated Haight-Ashbury neighborhood in the low-rent flats of San Francisco. Mainly unchaperoned teenagers, some of them college students on summer break—more of them drifters and malcontents, juvenile delinquents and thrill seekers—began showing up.

Fueled by drugs and electric music, the Haight-Ashbury district turned into a street carnival, teeming with young rebels and poets, flower children, and free spirits. The mood was intoxicating. Hunter S. Thompson later recalled: “You could strike sparks anywhere. There was a fantastic universal sense that whatever we were doing was right. … Our energy would simply prevail. There was no point in fighting—on our side or theirs. We had all the momentum; we were riding the crest of a high and beautiful wave.” The press fanned the good-times and spectacle: free sex, plentiful drugs, electric rock and roll, higher consciousness, mind expansion, and utopia all at once.

The 32-year-old journalist Joan Didion, reporting the phenomenon less giddily, and old enough to be a creature from another era or planet, observed in her seminal 1968 essay, “Slouching Toward Bethlehem,” that “we were seeing something important. We were seeing the desperate attempt of a handful of pathetically unequipped children to create a community in a social vacuum.”

That summer, at a meeting on behalf of the Haight-Ashbury Free Clinic, I declared that the invasion of “teenage derelicts” was disturbing. I got the fish eye. “Hey man,” a power-trippy young man named Mike interrupted in a threatening tone: “We’re all brothers here.”

Meanwhile, new standards for living were set. I met a young man who said about his rent, “It will take two months before we go through the courts. We’ll have two months of free living. That’s part of our thing anyhow. We’re teaching people to survive, be fed and clothed, without having any money.”

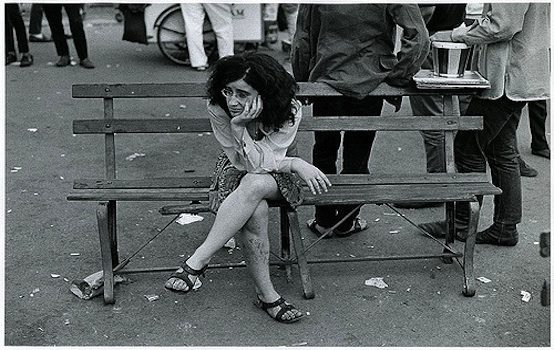

The rapture did not last long. By the winter of 1968, unhealthy-looking flower children were no longer dancing in Golden Gate Park but trying to cadge spare change and pissing into the juniper plants. The college kids had gone back to class, spreading the new counter-cultural gospel. More than a year before Woodstock, the wave was crashing. The innocent charm and beauty of the early counter-culture was unwinding.

The Summer of Love sought to break free of censorious conformity and celebrate expressive individualism. It was detached from the early anti-war movement. St. Pepper and Bob Dylan, Aldous Huxley and Timothy Leary, not Mario Savio or Karl Marx, were its sentinels. In time, ironically, Sixties rebels gained footing in academe, government and the corporations they despised, becoming elites in revolt, “blame America first” Democrats, and champions of identity politics.

In 1967, the culture of narcissism was going mass market, and Cyra McFadden’s The Serial (1976) would brilliantly satirize with-it Marin County “yuppies” who had adopted the bohemian café and black leotard lifestyle, seeking to bring Aquarian hipness to regimes of work and family. Their grandchildren might be at Middlebury and Claremont colleges today, still spewing the idiom of the Sixties.

The counter-culture validated styles of living once considered coarse, delinquent, tragic, or mad. It was said to be about Love. Was that eros, or philia, or agape? One cannot be sure, but the gross hypersexualization of entertainment and culture since suggests eros, down and dirty.

Whatever the collective mental impact, Sixties rebels got used to breaking and flouting the law, dealing and using illegal drugs. Good estimates and polling tell us that perhaps nine percent of U.S. adults have used LSD, and 42 percent, marijuana, at what cost to the human mind and what else, who knows. (Still, realistically, legalization might be the best and only possible means of dealing with rampant drug use and addiction today.)

In 1967, the Jefferson Airplane’s Grace Slick sang proudly in the midst of the Vietnam War, “I’d rather have my country die for me.” Three years later, late to the game, Charles Reich at Yale University published The Greening of America, revealing to credulous New Yorker readers that Consciousness III would soon deliver the nation and humankind from bourgeois tedium. How romantic. How wrong.

Historians incorrectly point to the 1969 Woodstock festival as the signal event in the youth culture’s arrival. The Summer of Love ignited the loose, Dionysian culture that is inescapable today. The raunch and debauchery, radical individualism, stylized non-conformity, the blitzkrieg on age-old authorities, eventually impaired society’s ability to function.

The Summer of Love indicated the future was not all going to be the Tao and weekends in Tassajara. The counter-culture was also going to be about blown minds and insane political causes. The marvelous, charismatic Zen hero Alan Watts would die alcoholic in 1973. The sinister, the dark side, and unchained id were already insistent, not only in music. Charles Manson’s Helter Skelter and the Symbionese Liberation Army were already on the horizon.

Gilbert T. Sewall is co-author of After Hiroshima: The United States since 1945 and editor of The Eighties: A Reader. He is a 1967 graduate of the University of California, Berkeley.