Shirley Hughes’s Conservative Imagination

The children’s author, who died this year, produced a treasure trove of stories teaching children to love the normal, local, and traditional.

A new school year means new books for grade schoolers, though one notable children’s author’s literary journey has sadly reached its end this year: Shirley Hughes. The British author and illustrator, whose books sold more than 11 million copies worldwide and earned her many awards, died in February at her home in London after sixty years at the easel. It is a loss not only for children, but for parents who delighted in her many books, which in their unobtrusive beauty could be called conservative in the very best way.

My family was first introduced to Shirley Hughes while we were living in Thailand several years ago. The owner of the largest and most accessible English-language collection of books in Bangkok was a 150-year-old private library adjacent to the British Club (annual family dues were only $100!). Unsurprisingly, a disproportionate percentage of the books were from the United Kingdom rather than the United States. And many of those were by Shirley Hughes.

Hughes's children's books immediately stand out from the rest. Every single page features a work of impressive artistic quality—Hughes studied at the Liverpool School of Art and later attended the University of Oxford’s Ruskin School of Drawing and Fine Art. In an era when many children’s books rely on cheap computer graphics, it’s refreshing to discover an illustrator who obviously labored, with deep attention to detail, over every page.

It's not just the illustrative talent and distinctive style using pen and ink, watercolor and gouache, to “infuse ordinary domestic scenes with a mixture of coziness and magic” that sets Hughes's works apart. She was also an expert storyteller. That’s not because her stories are particularly imaginative; indeed, none of her books flirts with the fantastical (though there are a few fairy tales). Rather, perhaps counterintuitively, it’s the simplicity and normality of the stories that make them so pleasing to kids and parents alike.

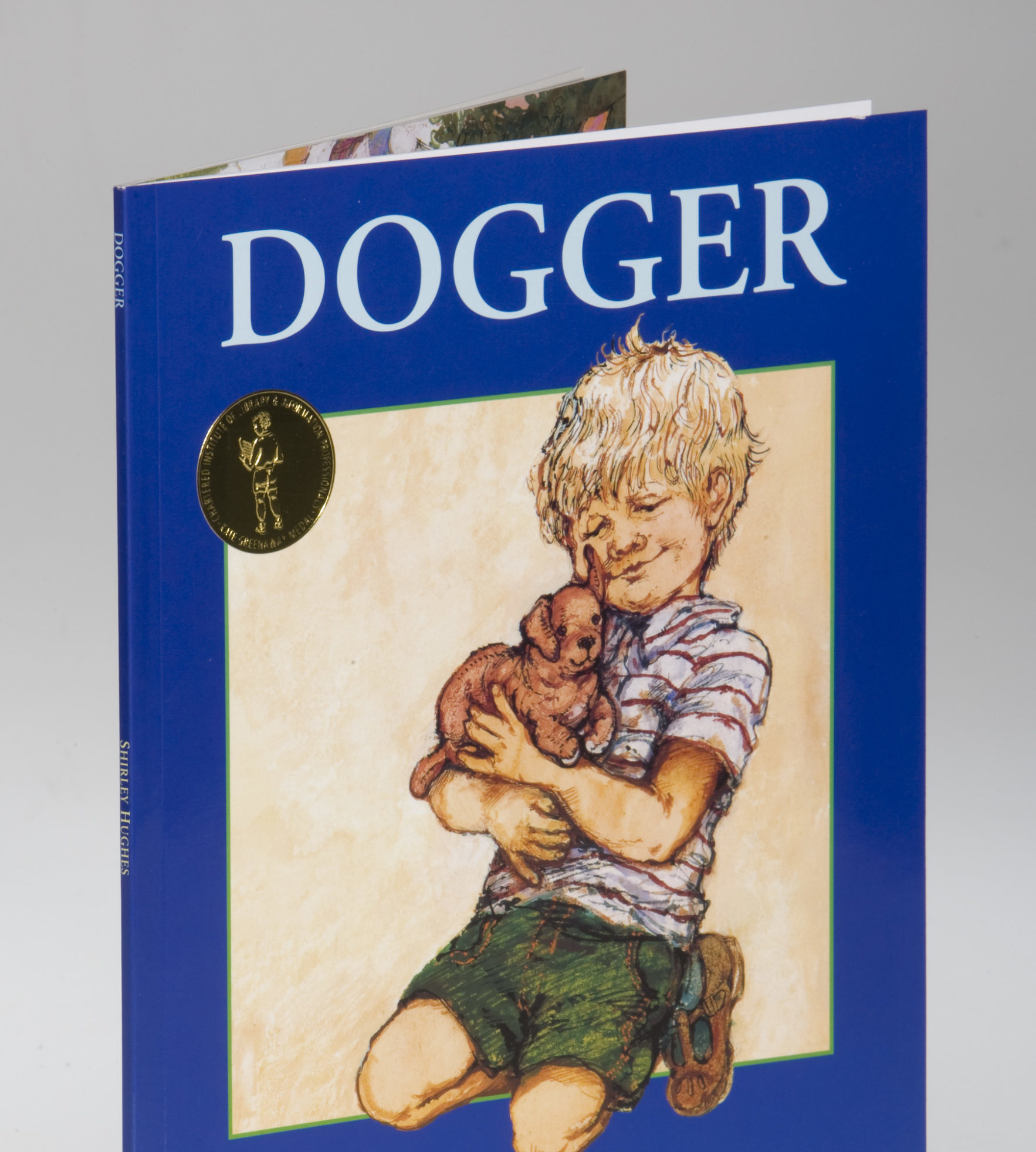

Take Dogger, one of Hughes's earlier books, published in 1977, which sold millions of copies and won Britain's Kate Greenaway Medal. Dogger is the story of Dave, a young boy who loses his beloved stuffed dog when he and his mother and younger brother go to pick up his sister at school. (Presumably, Dave drops the dog when he is distracted by his mother buying ice cream for him and his siblings.) It also features a school fair the following day, with entertaining pictures of, among other things, children dressed up in silly costumes, a fathers’ race, and adults in bell-bottoms (it was the ‘70s!). And, of course, there is a happy, heart-warming resolution.

Much of what makes Dogger and the rest of Hughes's corpus so engaging is that the stories are told from the perspective of the child encountering everyday events—some of which are novel and thus exciting or scary, others that are familiar and thus comforting. What’s more exciting for a four- or five-year-old boy than going to a school fair with games, prizes, and even parents joining in on the fun? And what’s more comforting than going to sleep beside one’s favorite toy, with the child-like confidence that one’s parent’s outside the room are there for constant protection? Hughes has a special skill for describing the life of the child from his or her own perspective, drawing wonder out of what we often assume to be boring and uninteresting.

In her beloved Alfie series, we follow around the eponymous well-mannered little boy and his sister Annie Rose as they experience all the kinds of events that define youth. Alfie attends a birthday party for his best friend Bernard, who, like many five-year-olds overwhelmed by the attention, acts like a complete brat. Alfie and Annie Rose—with help from mom and grandma—set up a make-believe shop in their backyard, using acorns and leaves as currency. Alfie receives a new pair of rainboots and has trouble learning to put them on the right feet; he accidentally locks his mother and Annie Rose out of the house upon returning from the grocer.

Though I have a graduate degree in education, I never would have expected my children to love these stories. Where are all the silly rhymes, crazy creatures, and absurdist storylines? But my children do love them. My best guess is that it is because Hughes's books talk to them about the kinds of things they witness and experience daily. By extension, these books tell them in reassuring tones that, yes, their little world with all of its people and curiosities is quite interesting indeed.

These stories also evince a peculiarly conservative conception of childhood. “She could create a sense of drama out of the smallest thing and resolve it without ever needing to deliver a message,” noted the Guardian’s obituary earlier this year. “Instead, she relied on children and their parents being largely sensible and so able to solve problems for themselves.”

I’ve also yet to read a Hughes's book with a broken family—perhaps there is one, but of the dozens of stories I’ve read to my children, the working presumption is always that families are intact, and that mothers and fathers love one another and treat their children with deep affection. There’s also a strong sense of community and appreciation for the working-class men who make the world work—stories involve milkmen, painters, and movers, all depicted sympathetically as integral members of the neighborhood. And there’s a cherishing of creation and the bucolic, with tales of visiting family in the countryside and marveling at the unusual behaviors of wildlife and farm animals.

Subscribe Today

Get daily emails in your inbox

Church looms in the background of some stories, though less to preach some religious or theological idea than as part of what a full, authentic childhood is supposed to look like. There’s also a whimsical esteem for a past that reflects a simpler way of life, and even thoughtful, authentic considerations of various periods of English history. Forebears loom venerably in the background, such as in Hughes's poem “Statue,” about Alfie running around the “big stone man,” a statue of an unnamed, deceased English lord: “when everyone’s gone home / and the park’s closed / and it’s all dark, / he’s still sitting there”—not desecrated or torn down by woke mobs who despise the patriarchy.

Perhaps much of the reason I’ve so taken to reading Shirley Hughes to my own children is that it reminds me of what the world looked like when I too was a little boy, wandering around and enjoying puddles, trees, and ducks, or sitting at the window wondering what all those people are doing out there, and might they perhaps wave hello to me? It’s the kinds of things childhood is supposed to be about, not contemplating anti-racism, your gender identity, or, God help us, abortion. We must have our natural inclinations to enjoy and treasure the world encouraged and even enlarged before we’ll ever be able to prudently and productively critique it.

I’m sure Shirley Hughes had political opinions, perhaps many with which I would disagree. But whatever they were, her cultural sensibilities—which, in the Aristotelian sense, are essentially political anyway—were profoundly conservative: individual responsibility, respect for the past, appreciation for traditional families, and a love of the local. “If there’s anything wrong with childhood today,” she told the Guardian in a 2015 interview, “[it’s] that there’s too much on offer and everything moves at great speed. What I want children to do is linger, turn the page, see themselves as readers long before they can read.” That’s a pedagogy worth celebrating in the digital age.

Comments