Reconsidering Rudyard Kipling

Recently the students at Manchester University in England tore down a copy of Rudyard Kipling’s poem “IF” and replaced it with Maya Angelou’s “Still I Rise.” They gave as their reason that Kipling was an imperialist and a racist.

What’s interesting about this latest outburst of political correctness and cultural ignorance is that in a strange way the two poems are similar. Both tell the reader to be strong and fight against defeat and rejection in the idiom of their day, Kipling with his “buck up and play the game” and Angelou with her defiant stand against racism no matter the setbacks. My guess is that Angelou might have liked “IF.”

All this brings to mind something the American literary critic Edmund Wilson once wrote: that nobody reads Kipling anymore. I don’t know if this true—he is no longer in the canon of English studies taught in high school and college where some of his work was anthologized as late as the 1960s—but it’s a shame if it is because the caricature of Kipling as a simple-minded drum beater for the British Empire is superficial and naïve.

Consider the question of Kipling’s attitude towards the British. It was, in fact, complex. He was a great admirer of the independent dominions Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and South Africa. He saw them as part of the vast Anglosphere, including the United States, which had a unique role to play in the future. He was characteristic of those who believed in the destiny of what Winston Churchill called the “English Speaking Peoples.” Despite a certain ambivalence about Americans, Kipling admired their patriotism and energy. He was particularly fond of Theodore Roosevelt whom he nicknamed “Great Heart.” His wife was American and he lived in the U.S. for years, only to leave in 1899 after a petty legal dispute, never to return. One of Kipling’s most quoted—one could say misquoted—lines of poetry was directed at the United States. “Take up the White man’s Burden” had nothing to do with non-white peoples; it was describing the U.S. as it debated whether to annex the Philippines after the Spanish-American War in 1898.

It’s also worth noting that for someone regarded as a bloody-minded imperialist, Kipling was sensitive to the arrogance of empire. His poem “Recessional,” written amidst the celebration (and glorification) of Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee in 1897, reads less like a nationalist’s raving than a warning to the English people, with the the refrain capturing some of the excesses of the occasion:

Far-called our navies melt away

On dune and headland sinks the fire

Lo, all our pomp of yesterday

Is one with Nineveh and Tyre!

Judge of the Nations, spare us yet,

Lest we forget—lest we forget.

Kipling had mixed feelings about the British Empire in Africa and wrote relatively little about it. His poem about Africa that’s quoted most often, “Fuzzy Wuzzy,” takes a somewhat admiring view of Africans:

‘ers to you Fuzzy Wuzzy,

at your ‘ome in the Sudan,

you’re a poor benighted ‘eathen,

but a first class fighting man.

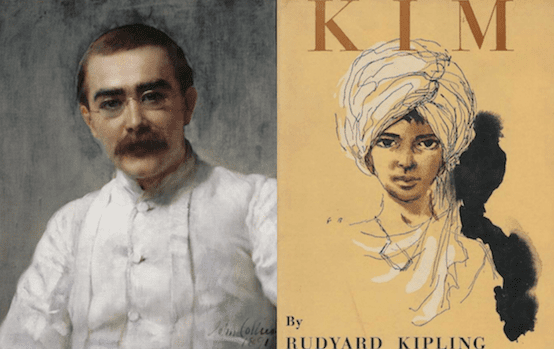

But Kipling felt his deepest affection for India—the part of the British Empire that he knew best. His poetry, and especially his short stories, set against the background of the golden age of the Raj, constitute some of his best work. Anyone doubting this has only to turn to some of his short stories set in India. “Without Benefit of Clergy,” with its powerful portrait of an English government official genuinely in love with an Indian woman, reveals the depth of Kipling’s admiration for Indian life as well as a grasp of the complexity of human relations we often don’t associate with him. His ghost stories set in India, especially “The Phantom Rickshaw,” also hold up well. The Jungle Book and Kim, perhaps his best novels, are not only set in India but their protagonists are Indian, not English.

Barrack Room Ballads, which appeared in 1892 and established Kipling’s reputation, for years provided some of his most-quoted verse: “Danny Deever,” “Gunga Din,” and “Mandalay,” were enormously popular well into the 20th century, at a time when public recitations were commonplace. George Orwell, an admirer of Kipling’s verse—he called it “good bad poetry”—observed that people tended to translate it from Cockney slang into standard speech. He also noted that at times Kipling transcended verse and produced pure poetry, citing the lines from “Mandalay”:

For the wind is in the palm trees, and the temple bells they say,

Come you back, you British soldier, come you back to Mandalay!

His poetry and short stories about the average British soldier or “ranker” are also powerful, if sentimental and marred by Kipling’s insistence on using English slang. Kipling admired the junior officers and the enlisted rankers as the best the English “race” produced. He used the word race as it was understood in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, as a national term, not a racial one.

The most productive and important part of Kipling’s career lasted for about 25 years and was over by the outbreak of World War I. The death of his beloved son, Jack, at the Battle of Loos in 1915 gradually soured Kipling on life. The new generation of writers in the 1920s and 1930s found him irrelevant and terribly dated. Interestingly, T.S. Eliot retained a certain fondness for him while noting that his tragedy was not that his work was denounced but that it was “merely not discussed.”

Despite a sharp drift to the political right after the war, Kipling managed to keep his balance. Although he shared the typical anti-Semitism of most upper- and middle-class Englishmen of his time, when some of his friends began circulating copies of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion right after the war, Kipling would have nothing to do with them and declared the publication a “fake.”

With his traditional distrust of Germany as an enemy of England, the rise of Hitler in the early 1930s disturbed Kipling. In 1932, he composed a poem, “The Storm Cone,” whose obvious target was Nazism, which it described as a “midnight” that is about to engulf Europe: “this is the tempest long foretold.”

Given the temper of the times, Kipling will remain anathema: his opinions and views are regarded as retrograde and odious to modern tastes. I note, however, that Netflix is set to debut a darker version of The Jungle Book, starring a cast of Hollywood luminaries, from Christian Bale to Cate Blanchett, in 2019. So maybe there is hope after all.

John Rossi is Professor Emeritus of History at La Salle University in Philadelphia.