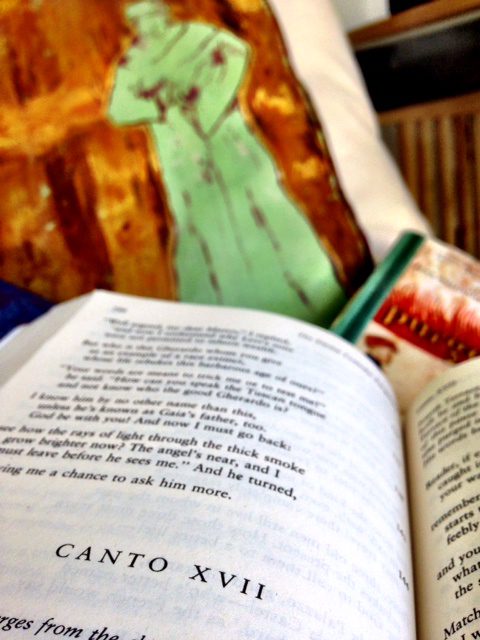

Purgatorio, Canto XVII

Tonight we reach the halfway point in our journey through Purgatorio; since Purgatorio is the middle book of the Commedia trilogy, this means we are at the halfway point of the pilgrim’s entire journey. Dante being Dante, he places the heart of Purgatorio‘s message here in the middle of the mountain. In this place, the pilgrim will learn the nature of sin: disordered love.

But first, as is customary as the pilgrim reaches the end of each terrace, he encounters three examples of historical figures destroyed by the vice purged on that terrace. Here, on the terrace of Wrath, they come in the form of visions sent by God. Dante loses all track of time in his mystical ecstasy.

my mind became, at this point, so withdrawn

into itself that the reality

of things outside could not have entered there.

Hollander says that there’s a charming story about the real-life Dante, in which he is said to have stopped at a bookseller’s stall in Siena, and lost himself in a book he had never read. He was so consumed by his reading that he didn’t notice a wedding party that took place all around him. In the poem, in this and earlier cantos, Dante (the author of the poem, not the character of the same name) seems to be establishing a basis for the artist as a visionary prophet. You can see why he takes the artist’s duty to be well-established in virtue, indeed in holiness, so seriously.

Orthodox Christians believe that a life of prayer and asceticism cleanses the nous, which is to say, the intellect, the faculty of a man’s being that communicates with God. To cleanse the nous is to open the soul to God, to remove the cataracts from the soul’s eye. From the Orthodox Wiki page on the nous:

Angels have intelligence and nous, whereas men have reason, nous and sensory perception. This follows the idea that man is a microcosm and an expression of the whole creation or macrocosmos; it is through the healed and corrected nous and the intelligence that man knows and experiences God. … The nous as the eye of the soul, which some Fathers also call the heart, is the center of man and is where true (spiritual) knowledge is validated. This is seen as true knowledge which is “implanted in the nous as always co-existing with it.”

Dante writes, of the visionary:

Light stirs you, formed in Heaven, by itself,

or by His will Who sends it down to us

The Christian wants to have his nous be as transparent as possible, so that the divine light can shine clearly through it. This is why it is so important for the artist who wishes to serve the Truth instead of the Self must labor constantly to purge himself of the tendencies toward sin, which is to say, everything that separates him from God.

That said, I confess that much of the Scholastic theology in this canto is simply beyond my clear understanding. I invite theologians who are reading Purgatorio with us to illuminate what Dante is trying to say here. I’m late posting this on Friday night because I’ve been trying to get a clear handle on the extent to which Dante’s Thomism informs the catechesis he puts in Virgil’s mouth in the Purgatorio, so I can discern which parts of the message is general to all orthodox Christian tradition, and which parts Orthodox and Protestant Christians would object to. Some things are obvious, but others are subtle, or at least I find them so. This afternoon, doing extra research, I ran across this passage in Etienne Gilson’s book, The Spirit of Medieval Philosophy:

… for St. Thomas, the divine likeness sinks for the first time into the heart of nature, goes down beyond order, number and beauty, reaches and saturates the very physical structure, and touches the very efficacy of causality.

This led me down several rabbit holes, which no doubt wouldn’t be rabbit holes for trained theologians, but which left me even more confused. Essence versus energies, Aquinas versus Palamas, Augustine’s concept of divine simplicity — my head was spinning from it all. To be clear, I don’t think that this degree of specific understanding is necessary to grasp most of the Commedia. I only want to register here that sometimes on this journey, even with good notes, I get the idea that I haven’t fully comprehended what’s being said.

Sorry for that digression. I’m really trying to work through this material diligently. I feel a sense of responsibility to tell you all, my companions on the journey, when I find myself lacking in understanding. The Commedia is deep.

So, once again, at the end of his sojourn on a terrace, Dante finds himself

struck by light across my eyes,

a light far brighter than is known on earth.

(I was reminded here of the arresting final moments of Terrence Malick’s To The Wonder; if you saw the film, you know exactly the frames to which I refer.)

Again, Dante is overwhelmed by the brilliance of the light. It is, of course, an angel of the Lord, come to remove another P from Dante’s brow, and to show the pilgrim and his master the way to the next terrace. Virgil says the angel “hides himself in his own radiance” — an instructive contrast to the black cloud of Wrath from which Dante has just emerged. He could see nothing in that cloud, and never would be able to see anything. Yet the cloud of light that Dante’s sight cannot yet penetrate is a cloud cloaking holiness. As we will find, the higher Dante ascends to perfection, the more transparent his nous will become, and the stronger his vision, such that he will be able to penetrate the mysteries concealed within the cloud of light.

The men ascend to the terrace where the sin of Sloth is purged. Why is Sloth sinful? Here’s Virgil’s explanation, from the Hollander translation:

“A love of good that falls short

of its duty is here restored, here in this place.

Here the slackened oar is pulled with greater force.”

The terrace of Sloth is an important bridge between the sins that came before, and those that come after. The earlier terraces — Pride, Envy, and Wrath — purge the more serious sins: those that are based on loving evil things. Now, Dante is entering the higher realms of purgation, where the sinful dispositions he confront have to do with loving good things in the wrong way. Sloth is what I am guilty of on this day: I failed to say my prayer rule in part because I fooled around too long with my head in the theology books. I love prayer, but I failed in my duty to my daily prayer rule out of slothfulness. It is a serious sin of mine.

Virgil goes on to explain that all actions are motivated by desire. We all love, which is to say, we all desire. If we desire the “primal good” — the will of God — above all, and make our lesser desires subject to God’s governance, we will be able to enjoy pleasures without sin. To order our desire, our power to love, rightly is to put the will of God first in our lives, and therefore to live well. Virgil continues:

But when it bends to evil, or pursues the good

with more or less concern than needed,

then the creature works against his Maker.

“From this you surely understand that love

must be the seed in you of every virtue

and of every deed that merits punishment.”

Musa puts it like this in his translation:

Natural love may never be at fault;

the other may: by choosing the wrong goal,

by insufficient or excessive zeal.

While it is fixed on the Eternal Good,

and observes temperance loving worldly goods,

it cannot be the cause of sinful joys;

but when it turns toward evil or pursues

some good with not enough or too much zeal —

the creature turns on his Creator then.

So, you can understand how love must be

the seed of every virtue growing in you,

and every deed that merits punishment.

This is the heart of the Commedia‘s understanding of the human condition and how to overcome it. The Fall disordered our loves. We are healed from the brokenness of the Fall by becoming properly ordered. Only Christ can fully perfect us in the next life, of course, but our salvation begins in this life, when we accept Him and begin the life of repentance. The life of the Christian on earth is about purifying our nous through prayer, ascetic labors (e.g., fasting) that cause us to die to ourselves, immersing ourselves in the Word of God, and receiving the Holy Sacraments, all of which open the doors of the soul to divine grace. The greater the grace, and the greater our surrender to God, the more we are transformed, such that we come to desire the Good. To desire the Good means to desire unity with God — and we will not cease our striving until we meet Him face to face.

If we love wrongly, Virgil goes on to say, that the disorders of love punished on the first three terraces — Pride, Envy, and Wrath — are sins that harm others. Pride, when we act as if our good depends on being superior to others; Envy when we resent the success of others because it makes us feel bad about ourselves; and Wrath when we long for vengeance on someone we believe has harmed us. (It’s important to note that Dante distinguishes between righteous anger and wrath, the latter being anger that seeks vengeance.) What unites these three is that they are sins that result in men loving things that cause suffering in others. They are inner sinful dispositions that primarily (but not exclusively) destroy the bonds of community.

The sins Dante will be purged of on the three highest levels, Virgil tells him, are sins that result from the immoderate love of good things — that is, making pursuit of secondary goods their primary goal, thereby turning them into sins. They are sins that primarily (but not exclusively) destroy the individual.

What are these sins? That will become apparent to Dante soon enough. First, Dante must walk the terrace of Sloth, where those who desire the good in a lukewarm way find their disposition punished. It’s interesting to notice that Dante finds Sloth more sinful than Greed, Gluttony, and Lust. As Robert Hollander notes, “By failing to respond to God’s offered love more energetically, the slothful are more rebellious to Him than are the avaricious, gluttonous, and lustful… .” Here is Jesus the the Laodiceans, in Revelation 3:16:

“I know your deeds, that you are neither cold nor hot; I wish that you were cold or hot. So because you are lukewarm, and neither hot nor cold, I will spit you out of My mouth.”

You can see where Dante gets the idea that slothfulness, and the indifference is engenders, is a condition more hateful to God than those who live passionately, if wrongly, for money, food, and sex. Better to have loved immoderately than never to have loved at all.

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.