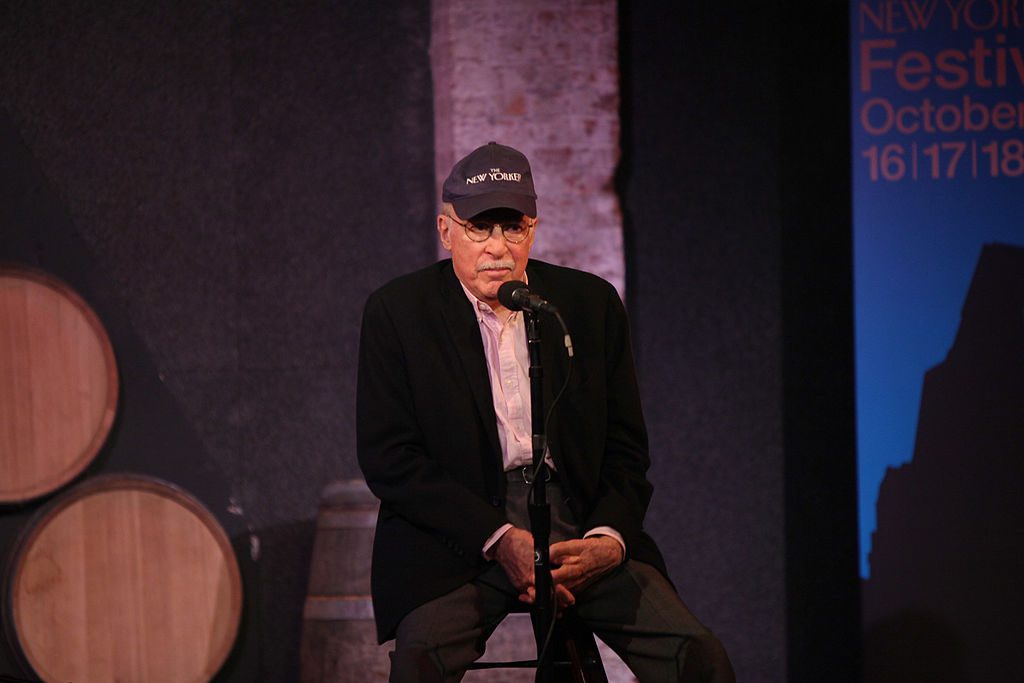

Roger Angell Turns 100

Roger Angell, a former fiction editor at The New Yorker and baseball writer, turns 100 on Saturday. In August, the small town in Maine where he lives celebrated his birthday early by putting on a “Roger Angell Day” and parade. Even the Governor came and gave a speech, though she had some trouble pronouncing the names of the players Angell used to write about, and he helped her out: “Gov. Janet Mills read a proclamation honoring Angell as he sat above her on the porch. She listed some of the baseball stars Angell had profiled, mangling many of the names. ‘Mordecai Brown,’ she said, using the pitcher’s given name. Angell shouted out his better-known nickname, ‘Three Finger!’ ‘Bill Mazurski,’ said the governor. ‘Mazeroski,’ corrected Angell. ‘Dizzy Vance,’ she said. ‘Dazzy,’ he yelled.”

Angell first started writing for The New Yorker in 1944 while he was still in the Air Force. (He never saw combat but served, first, as a machine gun instructor, then as managing editor of the military publication Brief.) His mother, Katharine Sergeant Angell White, was a fiction editor at The New Yorker before him. His step-father was E. B. White. In his memoir, Let Me Finish, Angell said this about his visits to his mother and White’s home in New York: “My mother and Andy White got married in 1929 … and though my sister and I were only weekend and summertime visitors with them after that, I soon felt as much at home at their place—on East Eighth Street and then East Forty-eighth Street, in New York, and then in Maine—as I was with my father the rest of the time. A fresh household sharpens attention, and one of the things I picked up was that sense of ease and play that Andy brought to his undertakings. Though subject to nerves, he possessed something like that invisible extra beat of time that great athletes show on the field. Dogs and children were easy for him because he approached them as a participant instead of a winner.”

Why not give Mr. Angell (and yourself) the gift of reading one of his pieces at The New Yorker? There’s “Storyville”—on the 18,000 pieces of fiction he had rejected and the hope of saying yes: “What is certain is that no one can read fiction for thirty-eight years, or thirty-eight weeks, and go on taking any pleasure in saying no. It works the other way around. You pick up the next manuscript, from a long-term contributor or an absolute stranger . . . and set sail down the page in search of life, or signs of life; your eye is caught and you flip eagerly to the next page and the one after that. Can it be? Mostly, almost always, it is not—or not quite.” Or how about “This Old Man”—on turning 90 (which was the last time Brooklin put on a Roger Angell Day)?

Thanks to Robert Messenger for alerting me to the local news story. I used to run crowdsourced fiction recommendations in this email. (Remember, “A Reader Recommends”?) It would be nice to do something similar for local literary stories. If you read something that might be of interest, send me a link.

In other news: The longtime CEO of Macmillan, John Sargent, will step down in January: “The shake-up comes after months of turmoil at Macmillan. The company was drawn into a dispute with libraries over its decision to delay the release of new e-books for library lending, a move that was meant to stabilize e-book sales but ended up angering the library market and was lifted during the coronavirus pandemic. Macmillan also imposed layoffs during the pandemic, a step most other major publishers avoided. This summer, employees at its Farrar, Straus & Giroux imprint started what became an industrywide walkout over racial inequity and the lack of diversity in publishing. And earlier this year, the company faced criticism for the decision by its Flatiron imprint to publish the novel American Dirt, which was attacked for what critics called a stereotypical and insensitive portrayal of Mexican migrants.”

Andrew Ferguson considers stupidity: “It’s a slippery, ill-defined word, steeped in relativism and subjectivity. Perhaps for that reason the subject has drawn the attention of modern intellectuals, from Robert Musil in the 1930s to Eric Voegelin in the 1960s, and on up to an eruption of publications during the George W. Bush years, books with titles like Just How Stupid Are We? and The Assault on Reason, along with blockbuster magazine articles such as the Atlantic’s 2008 cover story “Is Google Making Us Stupid?” After a dormant period, the field of what we might call Stupidity Studies is being enlarged, with the appearance of two more scholarly cracks of the whip. Together the new books give us insight into how some of our brightest minds understand the workings of minds that shine rather more dimly than theirs.”

Allen C. Guelzo reconsiders Robert E. Lee: “No one who ever met Robert Edward Lee — whatever the circumstances of the meeting — failed to be impressed by the man. From his earliest days as a cadet at West Point, through 25 years as an officer in the U.S. Army’s Corps of Engineers and six more as a senior cavalry officer, and then as the supreme commander of the armies of the Confederacy, Lee’s dignity, his manners, his composure, all seemed to create a peculiar sense of awe in the minds of observers. In the midst of the battle of Fredericksburg in December 1862, Lee astonished Francis Charles Lawley, the London Times’ special correspondent in America, for ‘the serenity, or, if I may so express it, the unconscious dignity of General Lee’s courage, when he is under fire.’ Abraham Lincoln remarked that a photograph of Lee showed that Lee’s ‘is a good face; it is the face of a noble, noble, brave man.’ Not even Ulysses Grant could escape the sense of being upstaged by Lee when they met at Appomattox . . . These impressions appear so consistent, and over so many years, that it has been easy to conclude that dignity, manners, and composure simply were the man, that there was (as Douglas Southall Freeman insisted at the end of his four-volume biography of Lee) ‘no mystery’ at all to Robert E. Lee. Or, as Burton Hendrick wrote (in The Lees of Virginia), that ‘Lee’s character’ was ruled by a ‘great simplicity,’ or that (in the words of an even more worshipful biographer, Clifford Dowdey) Lee ‘could rest totally . . . in very simple things.’ However, this picture of straightforward, well-nigh angelic serenity sits uneasily beside moments when cracks and inconsistencies in that fabled serenity appeared.”

Style cannot be taught, Joseph Epstein writes in First Things, but “it can be learned in one way and one way only. This is by reading those writers who have achieved mastery”: “Books on how to write abound, but none that I know is very helpful. Books that address specific problems, of grammar, of punctuation, of usage, are more useful. On usage nothing surpasses H. W. Fowler’s Modern English Usage, first published in 1926 and, mirabile dictu, a modest bestseller when it first appeared in America . . . From Aristotle through Horace, Tacitus, and Quintilian, on to Edgar Allan Poe, Walter Raleigh, and Arthur Quiller-Couch, up to Strunk and White’s Elements of Style in our own day, there has been no shortage of manuals on oratory and writing. The most useful, I have found, is F. L. Lucas’s Style, partly because it does not pretend to instruct, but in even greater part because of the wide-ranging literary intelligence of its author, whose own style, lucid, learned, authoritative, rarely fails to persuade.”

Stephen Schmalhofer on the mother of Napoleon in Rome: “She first arrived in Rome when her son was First Consul and her half-brother, Cardinal Fesch, served as Envoy from the French Republic to the papacy. Napoleon always listened to his mother’s advice. She was a woman of practical judgment. ‘Here was the head of a man on the body of a woman,’ Napoleon told General Gourgoud . . . When Napoleon made his brothers Joseph, Louis, and Jérôme kings of Naples, Holland, and Westphalia, respectively, she was called Mater Regum—Mother of Kings.”

Photos: 2020 Tour de France (which ends on Sunday)

Receive Prufrock in your inbox every weekday morning. Subscribe here.