Kipling in America, a Defense of Updike, and WWII’s Lost Art

I hope everyone had a festive Fourth. Our week in the Carolina mountains was perfect. I hardly touched the computer, read (was disappointed with Waugh’s Gilbert Pinfold but enjoyed Maugham’s Of Human Bondage, which I haven’t quite finished), and rode a bunch of trails and roads. The mountains are so lovely in the summer, but there is also something wild and lonely about them that makes me want to tame and escape them in equal measure. (Thomas Wolfe captured something of the wildness of the Appalachians in Look Homeward, Angel but not much of the beauty.) More on this at some point, perhaps, but I’ve got a lot of catching up to do, so let’s get down to business.

How about starting your morning (and extend last week’s holiday a bit) with a couple of pieces on Brits coming to America? Did you know that Edward Whalley and William Goffe, two of the three signatories of Charles I’s death warrant, fled to New England when the monarchy was restored in 1660 with the return of Charles II? Edward Vallance reviews a new book on the pair: “Much of this interest, at least in the modern era, has been generated by the legend of the ‘Angel of Hadley’. The tale of how an aged William Goffe emerged from hiding to save the townsfolk of Hadley from an Indian attack caught the imagination of many novelists and poets in the early 19th century, including Sir Walter Scott, James Fenimore Cooper, Nathaniel Hawthorne and Robert Southey. Although an earlier generation of historians dismissed the legend as itself a work of fiction, Jenkinson notes that there is evidence suggesting the story may have a basis in fact: Goffe might indeed have assisted in the defence of Hadley in June 1676, but contemporary accounts may have deliberately obscured his role so as to prevent the elderly regicide’s discovery. The literary fascination with the regicides was, as Jenkinson ably demonstrates, built upon the historical recovery of their lives, which was given impetus by the revolutionary politics of the latter half of the 18th century. For New England Puritan ministers such as Jonathan Mayhew, the regicides were not ‘king-killers’ but men who had shown legitimate resistance towards a tyrant. As the dispute between Britain and its colonies grew more severe, Charles I increasingly became the ‘bête noire’ (as Jenkinson puts it) of North American preachers. Conversely, as Alfred Young demonstrated, those attacking British rule in the colonies in New England newspapers and periodicals increasingly deployed the names of Parliamentarians, including Whalley and Goffe, as noms de plume.”

Charles McGrath reviews Christopher Benfey’s book on Rudyard Kipling’s American years: “In a prologue to If: The Untold Story of Kipling’s American Years (Penguin Press), Christopher Benfey, a professor at Mount Holyoke, writes that some of his friends, when they learned what he was working on, asked him what on earth he was thinking, and warned that he’d better be ready to defend himself. Benfey’s best defense turns out to be the book itself, which doesn’t attempt a full-throated rehab job. An Americanist who has written very good books about Emily Dickinson and Stephen Crane, among others, Benfey mostly steers clear of Kipling’s politics, and instead concentrates on a little-known chapter in Kipling’s life: the four years that this outspoken defender of the British Empire spent living just outside Brattleboro, Vermont, where he wrote some of his best work, including The Jungle Book and The Second Jungle Book, Captains Courageous, and the first draft of Kim. Kipling’s American sojourn is hardly an ‘untold story’—it figures in all the biographies—but Benfey tells it well, catching nuances that some biographers have missed.”

The visionary architecture of Claude Parent: “Trained in classical architecture at the Beaux-Arts in France during and after the War but disaffected with Doric capitals, Parent graduated from the school able to draw anything. But what the rebellious student really wanted to draw wasn’t clear, and he spent years gradually developing a vision, eventually using drawing itself as a tool of liberation and invention. The functionalism of Le Corbusier, who said a house is ‘a machine for living in,’ wasn’t enough for Parent. In the French (and international) context, Parent found Corb’s modernist machine too limiting, and it certainly didn’t open the door to the other side. Its Euclidean format lacked nuance and subjective shading, and offered no intimations of otherness. Parent rejected the boxed room, the boxed building, and cities of boxes, and set out, like Columbus, to sail to a new utopia beyond textbook geometry.”

I can’t say I really care about this, but I am passing it on to you, dear reader, in case you hadn’t heard and wished to be informed that Mad magazine is all but dead: “After the next two issues, a publication that specialized in thumbing its nose at authority will no longer include new material, except in year-end specials, according to two people with knowledge of the decision. Instead, the ‘usual gang of idiots,’ as the staff has long called itself on the masthead, will fill the magazine’s pages with old material.”

Documenting the blues: “Timothy Duffy is on a mission to document America’s vernacular music — specifically, the blues — and the everyday men and women who carry on the tradition. He’s the co-founder of Music Maker Relief Foundation, a nonprofit that helps struggling and aging musicians. Duffy is also a photographer, and his new project is a collection of portraits of these musicians, who are not typically in the spotlight. It’s the subject of an exhibition at the New Orleans Museum of Art through the end of July. Duffy’s vivid black-and-white portraits, captured with an early photographic process called tintype, are also collected in the new book, Blue Muse: Timothy Duffy’s Southern Photographs. The book includes a compilation album so you can hear the music behind the faces.”

Hazel Wood recommends Period Piece: “For me, a home without Period Piece is like a house without a cat — lacking an essential cheering and comfortable element. I have loved Gwen Raverat’s memoir of growing up in Cambridge in the 1890s ever since I first read it 20 years ago when recuperating from a bad bout of ’flu, at that blissful moment when you are feeling better but not quite strong enough to get up and do anything. I can still recall the delicious feeling of reading and dozing, dozing and reading, snug in the gas-lit world of Victorian Cambridge, until the January afternoon outside the bedroom window gradually turned purple and faded into dark.”

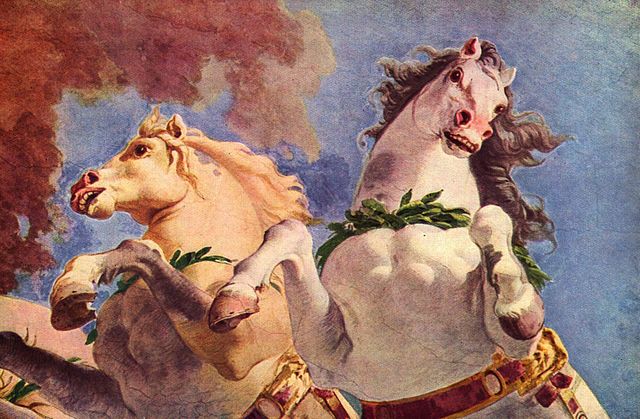

Revisiting the 18th-century frescoes destroyed during WWII: “Over the course of World War II, some 65 percent of Milan’s historic monuments were damaged or completely destroyed. The Palazzo Archinto’s treasures were among the causalities. While the majority of the building’s structure survived intact, on August 13, 1943, Allied bombing razed its interior, destroying a series of ceiling frescoes by Venetian painter Giambattista Tiepolo between 1730 and 1731.”

Essay of the Day:

I’m not a fan of John Updike’s work (though I don’t hate it either), but Claire Lowdon’s defense of it, and of the importance of judging a work by its style, not its politics, is a breath of fresh air:

“The things we smell in Updike’s work, or Bellow’s, are as indicative of our own time as of theirs. And times change very quickly. Readers in their early thirties might consider themselves woke millennials – but how many of them, in their schooldays, used the word ‘gay’ as a general pejorative? Leader’s biography of Bellow relates how his final novel, Ravelstein (2000), a roman-à-clef, landed Bellow in trouble for implying that Allan Bloom (the real-life model for Ravelstein) was homosexual and died of AIDS. From the vantage point of a scant two decades, the squeamishness of this critical response already looks quaint. Who knows – in another two decades, 2019’s heated discussions about race and gender may look equally quaint . . .

“If we lift our muzzles from the scent trail of sexism in Updike’s early work and look around, we find ourselves standing firmly in the past. This for me was one of two great surprises on recently reading Updike’s debut, The Poorhouse Fair. The novel was published in 1959, when Updike was twenty-six. Like Toward the End of Time, it’s actually set about twenty years in the future. By the time Updike wrote the introduction to the 1977 Knopf reissue of the novel, included in the Appendix of the new Library of America edition, most of the novel’s ‘predictions’ had already been invalidated. For the modern reader, it’s about as futuristic as Adam Bede is historical, ie not at all. The ‘futuristic’ elements barely register, apart from as odd inaccuracies – one character notes how ‘of the three presidents assassinated, all were Republican’.

“What you notice instead is how long ago it all seems. We think of Updike as a fairly modern, fairly suburban novelist, a frequenter of golf clubs and diners. But John Hook, the key protagonist of The Poorhouse Fair, is ninety-four, with memories stretching back to the nineteenth century. Updike was born in 1932, and his maternal grandparents shared the family home. It sounds obvious but it’s still worth stating: Updike was well acquainted with the generation born around the time of the American Civil War.

“The second astounding thing about The Poorhouse Fair is what an unusual debut it is. In fact, Updike had started with something much more conventional, the unpublished novel Home: in Begley’s paraphrase, ‘the Olinger chronicles presented as a continuous narrative stretching from his mother’s teenage years to his own’. When Home was rejected by publishers, Updike set to work on something defiantly different. Set in a poorhouse – an old people’s home in today’s money – The Poorhouse Fair was intended by Updike as ‘a deliberate anti-Nineteen Eighty-Four’. Its vision of the future is not an imminent dystopia, but just more of the same. ‘As in our mundane reality, it is others that die, while an attenuated silly sort of life bubbles decadently on.’ Thus The Poorhouse Fair is both a surprisingly modest starting point and an extremely ambitious one: a twenty-six-year-old imagining himself into the mind of a ninety-four-year-old! Updike also inhabits the consciousnesses of various other residents, as well as Conner, the young, harried prefect, Ted, the even younger delivery boy, and several visitors to the poorhouse’s annual fair.

“Read as a debut it is deeply impressive, and it’s exciting to watch Updike honing the lyrical descriptive gifts that characterize and enrich his later work. (‘The boys kept edging one behind the other, like a deck of two cards shuffling itself.’) But you wouldn’t press The Poorhouse Fair on anyone, or rush to reread it. The major problems are overstuffed sentences and a formal shapelessness, a lack of focus, which Updike attempts to justify in the 1977 introduction. There, he quotes a sentence from the novel’s opening page. ‘In the cool wash of early sun the individual strands of osier compounding the chairs stood out sharply; arched like separate serpents springing up and turning again into the knit of the wickerwork.’ This, he tells us, is the novel’s pattern and import: ‘Life goes on; stray strands are tucked back … All is flux; nothing lastingly matters’. The great French braid of the generations, from the Civil War through Rabbit’s 1959 to 2019. (2019: one year shy of Updike’s dystopia in Toward the End of Time, which has not yet quite come about, because true to Updike’s earlier prediction, an attenuated silly sort of life has just bubbled decadently on.)

“Throughout his work, Updike is fascinated by time, hyper-conscious of that generational flux. ‘In a sense the poorhouse would indeed outlast their homes. The old continue to be old-fashioned, though their youths were modern. We grow backward, aging into our father’s opinions and even into those of our grandfathers.’”

Photo: 2019 solar eclipse

Poem: Wendy Videlock, “Whatever It Is”

Receive Prufrock in your inbox every weekday morning. Subscribe here.

Comments