Out of the Cold War?

Is America stuck in the Cold War or headed into a new one? Over the last 25 years, American grand strategy has had to do some heavy lifting to address the rise of terrorism—but it may have lost sight of the more dangerous threat posed by great power wars.

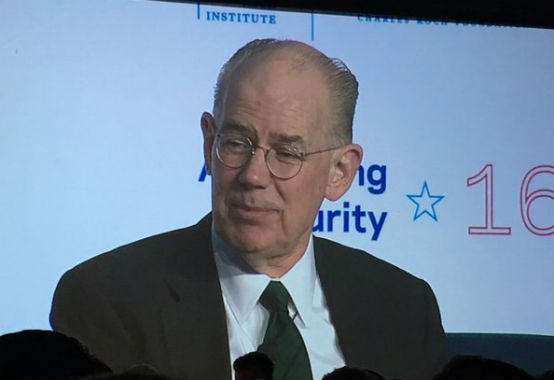

Worry over the deterioration of U.S.-Russian relations was a common theme earlier this week when powerhouses of realism and restraint met to debate foreign policy at “Advancing American Security,” a conference hosted by the Charles Koch Institute. The meeting brought together academics like John Mearsheimer, Barry Posen, and Stephen Walt with prominent D.C. policy experts, including Christopher Preble, Gian Gentile, and Michael O’Hanlon.

Although designed to “examine the past, assess the present, and explore the future of U.S. foreign policy,” many of the panels touched on Cold War vs. post-Cold War grand strategy.

CKI Vice President William Ruger began by posing the question: “Has there been a coherent theme to U.S. foreign policy over the last 25 years?” In response, Mearsheimer dove into a description of liberal hegemony over the last two decades, which essentially amounts to the U.S. being involved everywhere to avoid a problem popping up anywhere. He argued that the U.S. undertook this commitment to direct globalization and proceeded to muck up the Middle East and Europe. To most people, this sounds a lot like a vestige of post-Cold War triumphalism:

The basic foreign policy here is one of liberal hegemony—and it has two dimensions to it. The first is that we’re bent on militarily dominating the entire globe—there’s no place on the planet that doesn’t matter to the indispensable nation, we care about every nook and cranny of the planet and we’re interested in being militarily dominate here, there, and everywhere. That’s the first dimension. The second dimension is we’re deeply committed to transforming the world—we’re deeply committed to making everybody look like us.

Kathleen Hicks went even further in her answer, and claimed that there has been continuity in American grand strategy since 1945:

I actually think there’s been incredible continuity since the end of the Second World War and it just continued on post-Cold War. And that’s really, to start really where John started, it’s about the advancement of U.S. interests by leading in the world and I think that has been a very consistent theme in how each administration has pursued that. Particularly for following the end of the Cold War [each president] has definitely varied how each of those interests they’ve been most attuned to: economic, human rights and international order and/or U.S. physical security and the security of its allies, and how they’ve chosen to implement that, I think has varied to some extent but there’s an incredible continuity I think of 70-plus years in American foreign policy.

Since 1945, the U.S. has been through the Cold War, the Korean War, the Vietnam War, the First Gulf War, and a gestalt War on Terror that initiated military interventions of varying strengths in Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Yemen, Syria, Libya, and Somalia. The international hierarchy changed from bipolarity during the Cold War to unipolarity after the USSR’s dissolution. What does it say about American grand strategy if there has been continuity from the Soviet Union to ISIS?

It’s possible that the panelists are stuck in a Cold War mentality, though that’s unlikely. More probable is that the preoccupation with the Soviet Union and modern-day Russia stems from the fact that Russia has remained the only country capable of posing a significant threat to America’s position of power. China might be headed in that direction, but doesn’t seem to be there yet. Thus, Russia is one of the few threats that realists generally recognize as a valid danger.

Mearsheimer and Hicks offered broad policy suggestions for diffusing tensions with Russia in order to avoid a 21st century great-power war. Most importantly, slowly withdraw from NATO and turn it over to Europe. Both panelists said that contemplating the inclusion of Georgia and Ukraine was a mistake that resulted in Russian sensitivity to American overreach. Mearsheimer said, “We do not consider those countries (Georgia and Ukraine) of vital strategic interest but we were talking about including them in NATO which would give them an Article 5 guarantee.” Furthermore, he continued, NATO enlargement was not intended to contain Russia; its initial goal was the spread of democracy, liberal institutions, and economic independence.

Without a strategic rethink in U.S.-Russian relations, Mearsheimer warned that Russian paranoia and sense of vulnerability could ignite conflict. When asked about the biggest foreign policy mistake of the last 25 years, Mearsheimer first said Iraq, and then added the crisis in Ukraine and the resulting destabilization of U.S.-Russian relations: “If you take a country like Russia, that has a sense of vulnerability, and you push them towards the edge, you get in their face, you’re asking for trouble.”

Caroline Dorminey is an editorial assistant at The American Conservative.