Our Public Employee Problem

Congress declined to provide across-the-board salary increases for federal workers in 2011, 2012, and 2013. As a result, between 2010 and 2015, these workers’ pay grew just 2 percent while private-sector pay grew 10 percent thanks to the recovery. And yet federal employees still came out ahead—by a wide margin—when it came to compensation.

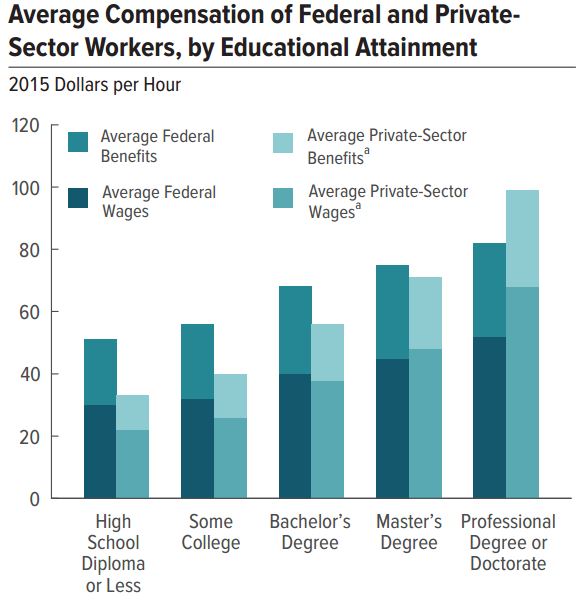

An eye-popping new report from the Congressional Budget Office reveals that on average, including both wages and benefits, federal workers receive compensation about 17 percent higher than comparable private-sector employees. Indeed, aside from those with the very highest degrees, Americans across the educational spectrum earn more if they work for the federal government than otherwise:

Of course, any analysis like this comes with a degree of subjectivity. Retirement benefits, for instance, are paid years after the work done to earn them was completed, and thus the CBO had to estimate these benefits’ “present value.” And because the federal workforce is not directly comparable to the private one—they attract different types of workers and tend to require different skills—the CBO needed to take into account a variety of characteristics, not just education but also “occupation, years of work experience, geographic location (region of the country and urban or rural location), size of employer, veteran status, and certain demographic characteristics (age, sex, race, ethnicity, marital status, immigration status, and citizenship).”

A different method of computing the “present value” of retirement benefits or a different combination of statistical controls might produce a somewhat different result. And the analysis doesn’t include other, harder-to-quantify benefits of working for the federal government, such as increased job security. But this is the newest evaluation of federal-employee compensation, conducted by the legislature’s official budget authority, and it shows that despite a three-year pause in automatic pay raises, federal workers are still getting paid a lot more than comparable employees in the private sector.

So where does that leave us? Let’s flesh out the CBO’s findings with some very rough back-of-the-envelope math.

Overpaid federal workers certainly can’t be blamed for the entirety of our budget woes. The CBO estimates that the federal government spent a total of $215 billion in 2016 compensating its civilian employees, which is much less than half of the budget deficit in that year. And if these workers were overpaid by 17 percent, they should have been paid $184 billion instead (215 divided by 1.17), a difference of about $30 billion. That is a mere 5 percent of the deficit.

It’s also, however, a considerable transfer of wealth to federal workers from everyone else. CBO reports that the federal government’s 2.2 million civilian employees are about 1.5 percent of the nation’s workforce, implying that this $30 billion burden is divided amongst fewer than 150 million non-federal workers. Those workers, then, are forking over about $200 apiece each year to pad the compensation packages the federal government offers. For our federal workers, meanwhile, that $30 billion means a surplus of more than $13,000 apiece, though as shown in the chart above the bonus varies by education level.

And federal workers are just the tip of the public-employee iceberg. At the state and local level the problems are different but if anything even more troubling.

Federal workers receive higher wages and better benefits than private-sector employees, according to the CBO, leaving little doubt that they are better compensated overall. But at lower levels of government, the picture is blurrier, with most studies showing public employees to receive lower wages but better benefits. This makes any analysis highly dependent on how benefits are valued and whether researchers make an attempt to include more subjective public-sector advantages like job security. Here is one study saying that public workers make 4 percent less than the privately employed. Here is another, though limited to California, saying that public employees are overcompensated by up to 30 percent once one makes a full accounting of public-sector benefits.

But whether or not non-federal public employees are overpaid for the work they do, their benefits are designed in a way that is wreaking fiscal havoc on governments nationwide. Where the private sector has largely switched to “defined contribution” pensions, where the employer contributes a specific amount while the employee is working (and future benefits depend on how the retirement fund’s investments perform), the public sector still uses the “defined benefit” model, in which the employer is obligated to provide workers a specific level of support in retirement—and governments have not funded their pensions well enough to provide the levels of support they have promised. Governments have often “assumed” the funds would earn higher returns than was realistic so they could contribute less, or even sent workers bonus checks during spells in which the funds performed well, leaving nothing to smooth out future downturns.

Future generations will have to make up the slack or file for bankruptcy—which under current law is an option for municipalities, as Detroit ably demonstrated in 2013, but not states. A 2014 Pew report put the funding gap for state-run pensions at close to $1 trillion. Closing that gap today would require every man, woman, and child in America to chip in almost $3,000, or state governments to dedicate a full year’s tax revenues to the pension shortfall alone.

It is perhaps inevitable that the government’s hiring and compensation practices will be less efficient than those of the private sector. Hopefully it is not inevitable, though, for public workers to be drastically overcompensated or drive our cities and states into insolvency.

Robert VerBruggen is managing editor of The American Conservative.

Follow @RAVerBruggen