Our Elites’ Selective Support for Democracy

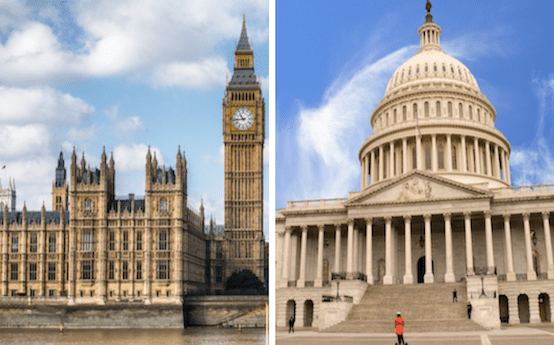

The ongoing parallel crises in the United Kingdom and the United States invite us to contemplate unwelcome truths about the nature of politics in the 21st century. In both countries, deep divisions have resulted in paralysis. In both, that paralysis represents something more profound: disagreement over the meaning and proper conduct of contemporary democracy. Yet there is little evidence that elites on either side of the Atlantic understand the actual problem at hand. Hence, the likelihood that it will fester.

In a nominal sense, their immediate problem centers on Brexit—how, or even whether, to honor the results of a 2016 national referendum in which a majority of voting Britons signaled their wish to leave the European Union. In a nominal sense, our immediate problem is a government shutdown. Yet overshadowing that shutdown is a persistent unwillingness to accept as legitimate the results of the 2016 presidential election in which Americans voted for Donald Trump in numbers sufficient to give him a majority in the Electoral College.

In both, the outcome of what was a manifestly democratic process confounded elite expectations. What happened wasn’t supposed to happen. In a few short months, the onward march towards a multicultural society and an integrated global order, with well-refined products of a carefully vetted and suitably diverse meritocracy pulling the strings, had been stopped in its tracks.

Overnight, an alternative vision of greatness—certainly the political term of the season—had presented itself. For Brexiteers, greatness meant returning to the glory days when the United Kingdom had been a power to reckon with on the world stage. For pro-Trumpers, it meant going back to when we made stuff that others bought and when identifiable national interests shaped U.S. foreign policy.

Whether the imagined utopia of a dominant Great Britain prior to 1914 or a dominant America after 1945 ever actually existed is beside the point. In 2016, large numbers of citizens in both countries concluded that the solution to their complaints was to be found in reasserting national independence, with Britain breaking free of the EU and the United States severing entanglements that have cost plenty without delivering discernible benefits.

When similar assertions of the popular will occurred in other countries—the protesters flooding Tiananmen Square in 1989, the crowds in Red Square that helped defeat the attempted putsch of August 1991, the 2011 uprising known as the Arab Spring—British and American elites cheered. At such moments, they are all-in for democracy. Yet when the exercise of democracy at home yields outcomes likely to affect their interests adversely, they sing a different tune.

Politics is always fraught with hypocrisy. Yet the hypocrisy on daily display in London and Washington of late has become difficult to stomach. This is especially so when it emanates from quarters that otherwise do not hesitate to chastise other governments for failing to honor democratic principles.

In a recent op-ed denouncing Brexit, New York Times columnist Roger Cohen wrote, “A democracy that cannot change its mind is not a democracy.” Let’s unpack that. What Cohen really means is this: when a democracy comes to a decision of which I disapprove, there’s always room for a do-over, yet when decisions win my approval, they become permanent and irreversible. So just because Americans elected a president who promised to withdraw from NATO and overturn Roe v. Wade doesn’t mean that such possibilities qualify as worthy of consideration. NATO membership is forever. So, too, are abortion rights.

It is no doubt true that the United Kingdom and the United States are democracies, with the people allowed some say. But to be more precise, they are curated democracies, with members of an unelected elite policing the boundaries of acceptable opinion and excluding heretics. Members of this elite are, by their own estimation, guardians of truth and good sense. They know what is best.

But what if the elites get things wrong? What if the policies they promulgate produce grotesque inequality or lead to permanent war? Who then has the authority to disregard the guardians, if not the people themselves? How else will the elites come to recognize their folly and change course?

Andrew Bacevich is TAC’s writer-at-large.