‘National Conservatism’ and Restraint

Jim Antle comments on the foreign policy portions of the recent conference on “national conservatism”:

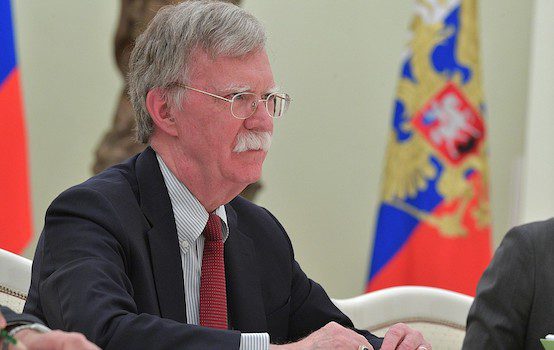

Nor was Bolton’s refusal to repeal and replace the Bush foreign policy anything unique. Several speakers made only the most cosmetic changes as they threatened Iran, defended Saudi Arabia, and otherwise watered down Trump’s campaign promises. Clifford May declined to be a “policeman of the world,” offering to instead be “sheriff,” saying intervention skeptics—he all but called them “isolationists”—were unwilling to protect America in the same way various television or movie characters in various Westerns were.

Looking over the schedule for the conference, I was struck by how many of the participants on the main foreign policy panel were extremely hawkish supporters of many of the administration’s worst policies overseas. For instance, Michael Doran was on the “National Conservatism and Foreign Affairs” panel with Clifford May. Doran is a leading Iran hawk, and he recently wrote a very long essay dedicated to promoting what he calls “a prolonged coercive strategy” against Iran that includes the threat of war. May is another hawk currently at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies (FDD), the main anti-Iran think tank in Washington, and he is the one arguing for the U.S. acting as global “sheriff.” The session’s chair was Colin Dueck, whose arguments for a “conservative realist” foreign policy I have frequently had reason to criticize for its lack of realism. Unless I am very much mistaken, there were no advocates of restraint or non-interventionists to be found on this panel. It would be easy to gripe about this, but it is more useful to consider why this is the case.

Part of the problem is that many of the people associated with “national conservatism” seem content to outsource their foreign policy thinking to the usual hawkish suspects, but that doesn’t fully explain it. The reality is that many of the conservatives and libertarians that favor foreign policy restraint and non-intervention don’t think of themselves as nationalists, and I think it is safe to say that many proponents of restraint see themselves as opponents of the sort of nationalism that Trump and Bolton represent. Bolton is a nationalist, and for him that means that the U.S. should behave in an aggressive, unilateral, and domineering fashion. His is a nationalism that sees threats almost everywhere and opts for carrying and using the “big stick” of force and other instruments of power to compel others to fall in line. It has a very expansive definition of what counts as being in the “national interest,” and it recognizes no real limits on what the U.S. can do overseas. Bolton’s nationalism is the antithesis of restraint in theory and in practice.

That gets to the larger question of what “national conservatives” want to do differently on foreign policy. Are they content with U.S. hegemony and its myriad obligations as long as they can get rid of the rhetorical Wilsonian window dressing and nation-building missions? Or do they want to redefine American interests narrowly so that those interests are much more limited and more easily defended? That hasn’t been settled yet, but if the hawkish participants at the conference are any indication it seems that many “national conservatives” still lean towards the former.

Comments