The Coup

Ah, Julius Caesar. That old middle school torture. Shakespeare’s most-heady, least-sexy play, the one Sam Johnson called “cold and unaffecting.” If you set it in ancient Rome, it’s apt to be a crashing bore. If you do it in modern dress, you can do interesting, even powerful things with the politics – but after Antony’s funeral oration, when actual civil war breaks out, the play falls apart, and the situation is apt to seem comical rather than affecting. How to teach this rather arthritic dog of war to once again cry havoc?

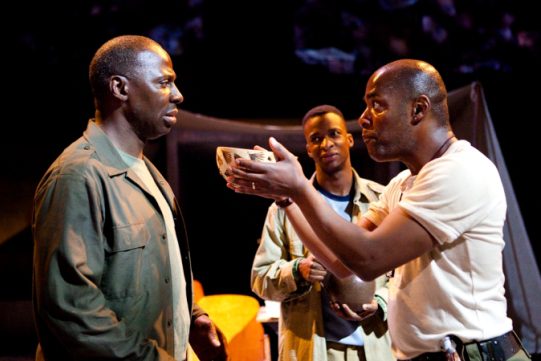

Well, the Royal Shakespeare Company’s Gregory Doran had an thought: set it in Africa, with an all black African cast. Caesar is the reigning populist dictator; Antony his energetic and good-looking right-hand man; and the conspirators are plotting a coup that will make them the new big men of the country.

At first glance, it sounds promising. Where, in a modern Western setting, the plotting and fighting would inevitably come off as metaphorical, in Africa coups and counter-coups are an all-too present reality. And then there are the supernatural elements; the soothsayer, certainly, should play better than usual. But the conceit runs into trouble almost immediately.

We open with the people celebrating Caesar’s triumph and anticipated ascension to the throne. (This process begins before the lights go down, actually – a move I always like, no matter how well-worn.) Then in come two men – “tribunes” in the text, but they are in uniform here, either gendarmes or soldiers of some sort – who chastise the people for their enthusiasm. Caesar’s triumph, after all, was over a fellow Roman – Pompei, whom once they loved. Why then do they cheer?

In the context of the play, the scene is intended to set the stage for Cassius’s entreaty to Brutus. The threat Caesar poses to the Roman constitution is potentially genuine – we know that because of the tribune scene; and the Roman people cannot be counted upon to do any more than follow the top dog – we know that from the same. Thus Brutus has a serious dilemma: the only way to save the constitution may be by violence, and yet violence may also fail. But, in this production, who do these uniformed scolders work for if not for Caesar himself? And if for Caesar, then why do they object to the public’s adoration of him? Right from the start, the African setting has muddled the politics, and that’s a huge problem for a play whose tragic hero takes politics, and political principles, very seriously indeed.

It gets worse with Cassius’s appeal to Brutus. Cassius (a bug-eyed, nervous Cyril Nri) talks his usual envious line of how he was a greater soldier than Caesar – but Brutus is supposed to be animated by some kind of noble idea. What is it? Why do these men talk about being reduced to the status of slaves by Caesar? What was their status before his rise? Who were they? Who are they? Whence comes their power? Brutus is supposed to be the reluctant conspirator, who loves Caesar but fears his ambition; if we don’t know what the idea is that animates him, then how is he any different from Cassius?

He isn’t, in this production. He’s “nobler” only in that he doesn’t take bribes and has a far more winning personality. But his trust in the nobility of Antony looks like pure political stupidity (which it is, of course, but it shouldn’t be only that) rather than principle; and his big speech before Caesar’s funeral saying that, though he loved and honored Caesar, he had serve him with “death for his ambition” falls grossly flat. What, other than ambition, has Brutus himself been fighting for?

The plus side of the conceit begins to show itself with Antony’s funeral oration, and carries through strongly into the tricky tent scene in Act IV. Ray Fearon makes an exceptionally plausible demagogue as Antony, and his segue from dictator’s right hand to would-be dictator coldly checking off names for execution has never seemed more natural. And for once, the tent scene really works. Brutus is as hot under the collar as Cassius is, and Cassius’s distress at apparently losing Brutus’s favor feels completely unfeigned. And when Brutus composes himself to “receive” the news of his wife’s death (news he already knows), it’s not a moment of chilly put-on stoicism. It’s deeply affecting.

Paterson Joseph’s Brutus turns out to be the most interesting performance in the show, as well it should be, but I can’t decide whether I finally thought it worked. This Brutus is anything but reserved – and, frankly, there’s not much about him that’s “noble” as we usually construe that word. He is honest, open-hearted, sincere; but his most shocking attribute is a sense of humor. He jokes (to the audience!) that he can read by the light of the comets and other celestial exhalations that prophecy Caesar’s doom; he laughs at his somnolent servant, Lucius (Simon Manyonda); he chuckles mordantly at his own army’s prospects in the coming fight at Philippi. He’s a very winning character – much more personally appealing than Antony, which is quite a novel reversal. For this novelty alone, the production is worth seeing.

It felt like this approach was a necessary alternative to making Brutus the noble defender of Roman liberties, because, in this production, we cannot identify what Roman liberties are to be defended, nor any obvious threat to them from this Caesar (as played by Jeffrey Kissoon, a rather out-of-touch old dictator, more Duncan than Julius, which only further suggests that Brutus is animated by ambition just like the other conspirators). But if we have nothing but personal qualities to draw us to Brutus, no higher purpose, then we can only be drawn to him if we forget, for a moment, that he’s an assassin, a traitor, a murderer. And if we forget that, then what’s left of Shakespeare’s play?

What’s left is a very affecting second half, which is not my usual reaction to productions of Julius Caesar. I don’t want to be too hard on Gregory Doran. Julius Caesar is an exceptionally tricky play. Most successful productions I have seen were actually successful only in the first half, and fell apart in Acts IV and V. This production seems consciously to have worked backwards, starting with the civil war and its end, and how to make that play effectively. As a consequence, for once the play gets stronger as it wears on. Which, come to think of it, is more fun than having a strong opening.

Julius Caesar plays at the Brooklyn Academy of Music’s Harvey Theatre through April 28th.