Medicare for All and the Myth of Free Markets

In 2010, the Affordable Care Act was heralded as a long overdue step towards universal healthcare coverage by Democrats, while Republicans called it “the most dangerous legislation ever passed in Congress.”

The best hopes and worst fears for Obamacare have not been confirmed, but the results have been disappointing. The result was not hard to foresee. Citizens were forced to buy insurance and medical care from healthcare monopolies with significant pricing power.

In theory, Obamacare moved the United States closer to universal healthcare coverage. Yet costs have continued to climb, 26 million Americans are still uninsured, and mortality rates have increased. In the 1970s, Americans typically lived longer than residents of other OECD countries. Today, the United States ranks 26th in the world for life expectancy, right behind Slovenia. More distressingly, life expectancy has deteriorated over the past two years.

The outcomes of Obamacare are so poor that another reform will be necessary. We will need a cure for the cure.

Democrats like Senator Bernie Sanders and Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez have offered Medicare for All as an alternative. However, if all it does is make the government the single payer without reforming the delivery of care, it will simply become Obamacare on steroids. Medicare for All could easily turn into an even bigger price-gouging opportunity for existing healthcare providers.

Republicans have long criticized Obamacare, but it has been almost a decade since it was passed and they have yet to propose a coherent alternative. Republicans seem bereft of ideas and are unable to take on entrenched insurance and medical lobbyists, reducing themselves to mere critics of the current system.

It would be almost impossible to create a more convoluted, uncompetitive, and byzantine healthcare system than the United States has today. Almost all of the countries in the developed world provide cheaper universal healthcare coverage for all. They also have better outcomes and longer life expectancy. Some offer government-run, single-payer systems and others offer a mainly private solution where the government guarantees that the poor are fully covered. They each differ, but they all succeed where the United States fails.

Each system has its pros and cons. For countries like Spain and the UK, a single-payer national system where the government taxes and provides medical care works, but the government also tends to ration the quantity of medical care on offer. In a mixed system like France, the government sponsors insurance, which is often supplemented by private insurance, while the delivery of medical care tends to be private. On the other hand, private insurance solutions work very well in the Netherlands and Switzerland, but consumers there restrict their own spending. All of these models achieve universal coverage at lower cost. The United States, by contrast, has the highest rate of uninsured citizens in the OECD, right behind Estonia and Mexico.

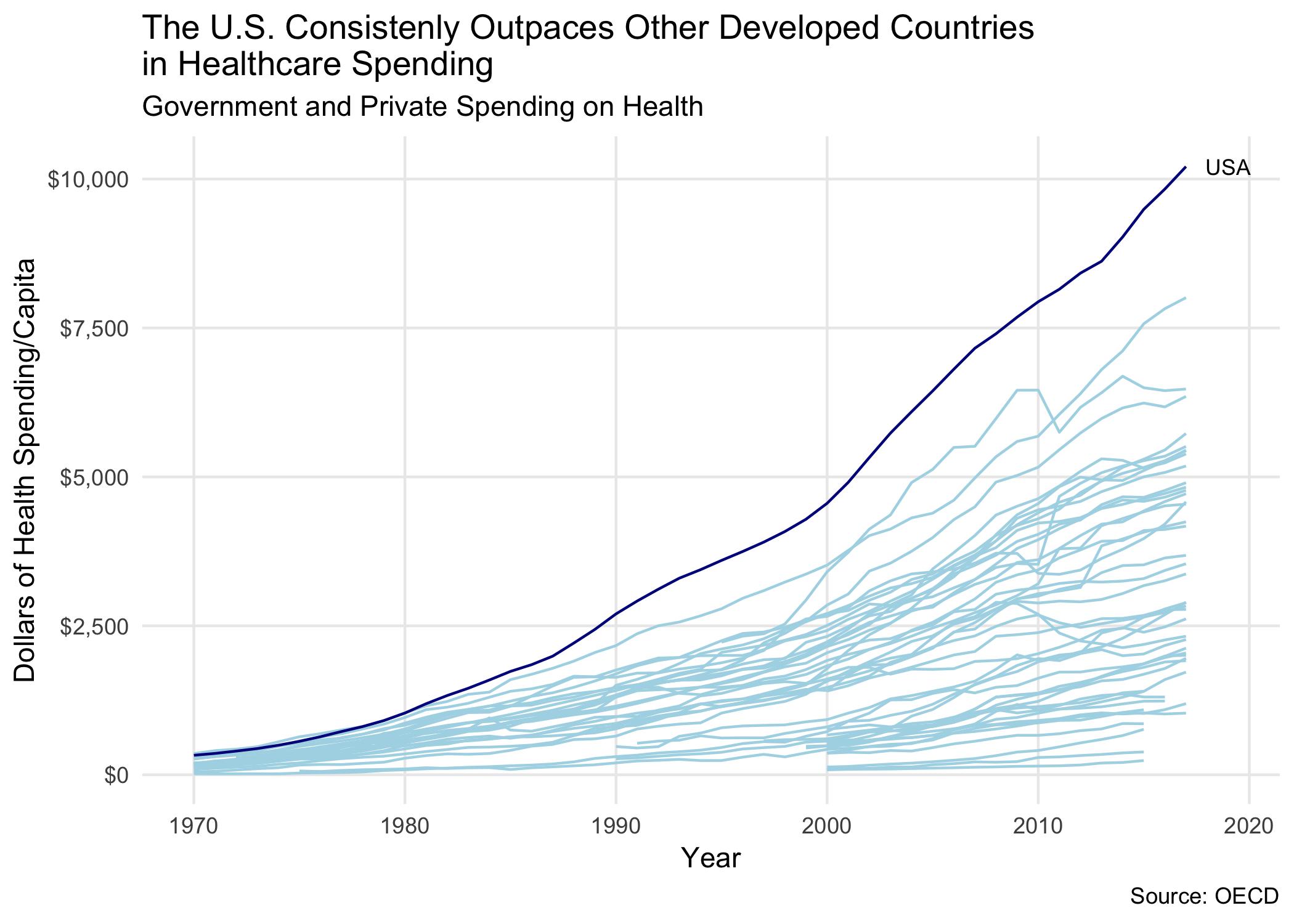

The United States does not achieve universal coverage, yet it still spends about 70 percent more than other developed countries with little to show for it. Americans with below-average incomes are much more likely than their counterparts in other countries to report not visiting a physician when sick, getting a recommended treatment or follow-up care, filling a prescription, and seeing a dentist.

No matter what reform the United States adopts, the choice is not between a socialized system and unbridled capitalism. Americans have the illusion that they live in a free market economy. But nothing could be further from the truth. Americans do not suffer from the monopoly of a government-run system, but the monopoly of private healthcare companies. The United States has the worst of both worlds: extensive government regulation and the monopolization of the healthcare market.

What accounts for the extremes in U.S. healthcare spending? At every single turn, the U.S. healthcare system is designed to limit choice and gouge the consumer.

Excessive government regulation prevents competition, and large insurance and medical monopolies are able to gouge the consumer at every step of medical care. The vast majority of Americans do not know how their healthcare system works. Judging by comments at congressional hearings, it is not clear that politicians understand how it works either. The following section should put to rest any idea that America has a competitive, free market healthcare system.

Insurance: The insurance industry is extremely concentrated and has no real competition. The McCarran-Ferguson Act of 1945 allows states to regulate insurers, and also makes selling insurance across state lines illegal. Many states have health insurance markets where the top two insurers have 80 to 90 percent market share. For example, one company in Alabama, Blue Cross Blue Shield, has an 84 percent market share; in Hawaii it has a 65 percent market share.

You can sell pencils, clothes, and soft drinks across state lines—but not insurance. As a result, the market for health insurance is extremely oligopolistic. United Healthcare, Aetna (which has merged with CVS in 2018), Cigna, and the Blues (Blue Cross and Blue Shield Association) have almost 90 percent market share nationally.

Insurance companies completely dominate their respective states. According to data from the Kaiser Family Foundation, there are at least 24 states in which one insurer covers more than 55 percent of the population, and there are 17 states in which a single insurer covers more than 65 percent. According to a 2014 study by the Government Accountability Office, the three largest insurers hold at least 80 percent of the total market share in 37 states.

Hospitals: Obamacare unleashed a hospital merger frenzy, but there were merger waves before the ACA. Nearly half of the country’s hospital markets are now considered highly concentrated. If you are sick, you have no choice where to go, and you have little to no ability to bargain.

There were 1,412 hospital mergers from 1998 to 2015. The number of hospitals has steadily fallen due to mergers from 6,100 in 1997 to 5,564 today, according to the American Hospital Association. The pace of hospital mergers has been accelerating. In 2015, 112 hospital mergers were announced nationwide; that’s 18 percent more than a year earlier, and a 70 percent increase over 2010.

Local monopolies raise prices for consumers. One study has shown that prices are 15 percent higher in markets with one hospital as compared to markets with four or more hospitals, a cost differential of $2,000 per admission. The evidence is devastating: concentration is bad, yet Obamacare has encouraged more and more mergers.

Studies of hospital mergers in the 1990s found that prices in highly concentrated areas increased by 40 percent or more. More recent work found that price increases following hospital mergers often exceed 20 percent.

The healthcare market is also consolidating vertically, and this has resulted in local monopolies of physicians. Hospitals owned 26 percent of physician practices in 2015, almost double from 2012. This increases their negotiating leverage and lets them circumvent anti-kickback laws by simply placing patient-referring doctors on the payroll.

Competition among hospitals in much of the United States is next to impossible. In 36 states and the District of Columbia, “Certificate of Need” laws force hospitals to get approval from a state’s healthcare regulator before making any major capital expenditures. This requirement creates formidable barriers for entry to any new hospitals. Decades ago, dominant hospitals wanted to prevent competition and potential oversupply, but the government should have no role limiting supply or allowing incumbent hospitals to fight against new entrants via regulation. A recent study of Certificate of Need laws showed that while on average there are 362 hospital beds per 100,000 people in the United States, states with Certificate of Need laws reduced that number by 99 beds.

Group Purchasing Organizations (GPOs): While you’ve probably never heard of them, four of these groups—Vizient, Premier, HealthTrust, and Intaler—control purchasing of more than $300 billion worth of drugs, devices, and supplies each year for 5,000 health systems, and thousands more non-acute care facilities.

The tale of these secretive organizations seems too farcical to be true, but it is. GPOs were created with the idea that if hospitals pooled their buying power, they could lower prices. Initially they might have helped, but over time they have raised prices and become leeches on the medical system. Unbelievably, in 1986, Congress passed a bill exempting GPOs from the anti-kickback laws. Rather than collect dues from hospitals that were part of the purchasing group, GPOs could collect “fees,” i.e. kickbacks, from suppliers as a percentage of sales. This skewed the incentives to inflating costs, rather than reducing them. Not only were they exempted from kickback provisions, but in 1996 the Justice Department and the Federal Trade Commission updated antitrust rules and granted the organizations protection from antitrust actions, except under “extraordinary circumstances.”

Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs): If you have drug coverage as part of your health plan, you probably carry a card with the name of a PBM on it. These organizations are gigantic middlemen, and as of 2016, PBMs manage pharmacy benefits for 266 million Americans. Today’s “big three” PBMs—Express Scripts, CVS Caremark, and OptumRx, a division of the large insurance company UnitedHealth Group—control between 75 percent and 80 percent of the market.

PBMs extract vast amounts of money from the medical system, with almost no public knowledge of their role. PBMs were formed in the late 1960s, and supposedly they would help process paperwork and by aggregating orders, reduce costs. However, the opposite has happened. Much like GPOs, they’ve been getting kickbacks from drug companies to put their drugs on the “formularies,” or lists of what drugs are approved for payments. They’ve also been getting very fat by hiking prices and taking their cuts as middlemen. Between 1987 and 2014, spending on drugs in the U.S. increased by 1,100 percent. The PBMs have been a major part of this problem. For example, Express Scripts’s profit per prescription has risen 500 percent since 2003, and its earnings per adjusted claim went from $3.87 in 2012 to $5.16 in 2016.

Drug Wholesalers: The Big Three drug wholesalers in the U.S.—AmerisourceBergen, McKesson, and Cardinal Health—handle more than 90 percent of the drugs in the U.S., due to dozens of acquisitions. Four out of every five drugs sold in the nation pass through the hands of the Big Three. They have been raising prices, and in 2017, the attorneys general of 45 states made sweeping allegations of price-fixing against McKesson, Cardinal Health, and AmerisourceBergen.

In banking, the problem of size is referred to as “too big to fail.” In other industries, you could refer to it as “too big to jail.” Since 2000, almost 250,000 Americans have died from opioid overdoses. The wholesalers have not been innocent bystanders. In 2014, the DEA found a small pharmacy serving a town just outside of Denver with a population of 38,000 that was prescribing 2,000 pills per day. When the pharmacy ran up against limits for reporting suspicious orders, McKesson simply raised the limits, again and again. The DEA found that McKesson was supplying enormous numbers of pills to pharmacies that were in turn supplying criminal drug rings. When pharmacies reached their limits, McKesson would simply raise them. This activity occurred at all 12 McKesson distribution centers that combined served the entire nation. Due to congressional lobbying, nothing has come of the DEA’s work. McKesson has paid a $150 million fine, which amounts to a rounding error for the company.

Pharmaceuticals: The United States spends over $3 trillion annually on healthcare, and 10 percent of that is spent on drugs. The average American spends more than $1,000 a year on prescription medications, 40 percent more than the next highest country, Canada, and twice as much as what Germany spends. In fact, the U.S. spends twice as much on drugs as the average OECD country.

The broadest study done on the reasons for the increase in costs appeared in the Journal of the American Medical Association. It concluded that “the most important factor that allows manufacturers to set high drug prices is market exclusivity, protected by monopoly rights awarded upon Food and Drug Administration approval and by patents.” Generic drugs are the main reason why drug prices have fallen, but access to them is generally delayed by numerous business and legal strategies.

The drug industry at one time was called the patent medicine industry, which is a much more accurate description of its true business. The pharmaceutical industry seeks endless extensions through “reformulation” of their drugs or minor modifications to the methods of delivery.

Reformulation involves changing the drug just enough to obtain additional patent protection. There is no new innovation, no new discoveries, and no greater benefit to patients, yet companies can continue to charge high prices.

Patents are a major hurdle to competition, but regulations and bureaucracy are an even greater barrier to entry. All new drugs are approved by the Food and Drug Administration. Generic drugs, though, are not new or unknown. Yet the current FDA approval process for generics is extremely onerous. On average, a generic takes between three and four years to be approved. Given how long this process takes, it is no surprise the FDA’s backlog of generic drugs stands at an all-time high.

According to Kaiser Health News, “The FDA had 4,036 generic drug applications awaiting approval, and the median time it takes for the FDA to approve a generic is now 47 months, according to the Generic Pharmaceutical Association.”

One immediate solution would be to allow drugs approved by European or Canadian regulators to be automatically approved in the U.S. For new medicines, that may not be a good idea, because it might lead pharmaceutical companies to shop for the easiest regulator. But for old medicines, this system would make sense.

In most countries, the government acts as a major purchaser of drugs and can drive down prices, much like Walmart drives down the prices it pays suppliers. However, in 2003, Republicans in Congress pushed through a law banning the federal government from negotiating lower prices for Medicare Part D, a new prescription drug benefit. This has handed billions of dollars to drug companies. The House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform found that taxpayers are paying up to 30 percent more for prescription drugs under Medicare’s privatized Part D program for seniors than the government spends for Medicaid.

In Europe, governments reward innovation and reduce prices using a system called “reference pricing.” The government, as buyer, groups drugs into classes based on their therapeutic effects. The insurer pays only the reference price for any drug in a class. If drug companies charge higher prices, a consumer can get the drug they want, but they pay the difference.

Kidney Dialysis: The U.S. dialysis market has become a duopoly after a series of mergers between DaVita and Fresenius. Approximately 490,000 Americans require dialysis treatment, and each company has almost a 30 percent market share. Much like the rest of the U.S. healthcare industry, DaVita has screwed the government and patients. In 2014 and 2015, DaVita paid $895 million to settle whistleblower complaints that the company conspired to overcharge the U.S. government. In 2017, the company received subpoenas after being accused of steering lower-income dialysis patients to private insurers to inflate profits, because DaVita was paid 10 times more through private insurance than through Medicaid or Medicare.

Intravenous Saline Solution: Monopoly is the last stage of capitalism, according to Lenin. Yet it was the Soviet Union that achieved a total monopoly in industries. When the Cold War ended, Moscow residents rioted because cigarettes were unavailable; the filter tips that were only produced in war-plagued Armenia had run out.

Americans are not rioting over cigarette filters. They are meekly accepting far worse shortages. In 2017, when Hurricane Maria devastated Puerto Rico, the United States faced a severe shortage of intravenous solution bags. Baxter and Hospira have an effective duopoly on IV bags, and their production facilities were located in Puerto Rico. (They had chosen the island due to its lower tax rates.) Even before the hurricane, price hikes were a problem. Prices in the U.S. have more than doubled in the last few years. A saline bag that cost $1.77 in 2012 is now more than $4, while the price has increased to only about $2 in the UK.

Saline solution is water and salt, so it may come as a surprise that something so simple is in the hands of only two companies. It is even more appalling that such a vital medical supply could be in such a shortage. Yet that is the story of the United States: high profits due to artificial scarcity at the hands of private monopolists.

♦♦♦

We could go on and on highlighting hidden monopolies, but it should be abundantly clear that the U.S. market for healthcare has no genuine competition, and markets exist to transfer money from patients to a small number of insurance, pharmaceutical, and hospital companies.

The cost to the country can be counted in the trillions of dollars, but the human cost is incalculable. In 1981, only 8 percent of personal bankruptcies were the result of medical bills. But 20 years later, illness and medical bills caused half of personal bankruptcies, according to a study published by the journal Health Affairs. Surprisingly, more than 75 percent were insured at the start of the bankrupting illness, but only 40 percent were insured by the time they filed for bankruptcy. In 2015, the Kaiser Family Foundation found that medical bills led 1 million adults to declare bankruptcy. Its survey found that 26 percent of Americans age 18 to 64 struggled to pay medical bills.

What can bring down prices? Genuine competition. Unfortunately, rather than introduce real competition by reducing barriers to entry and enforcing antitrust laws, Congress merely creates more concentrated industries, greater bureaucracy, and increased regulatory burdens. Increased regulation only raises the barriers to entry in almost all areas of healthcare.

The hammer of America’s antitrust laws has not been used, and every year we have seen more mergers among insurers, drug stores, hospitals, and pharmaceutical companies. The only way to improve costs and outcomes is to pass new antitrust and pro-competition policies to prevent mergers and bust up the monopolies and oligopolies that now dominate healthcare delivery in nearly every community in America.

Until competition is restored in U.S. markets, prices will not come down. If Republicans do not champion competition, the only alternative to private monopolies will be a government-run monopoly. Citizens may view it as a welcome relief from private tyrannies.

Jonathan Tepper is a senior fellow at The American Conservative, founder of Variant Perception, a macroeconomic research company, and co-author of The Myth of Capitalism: Monopolies and the Death of Competition. This article was supported by the Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation. The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors.