Mark Lilla Vs. Identity Politics

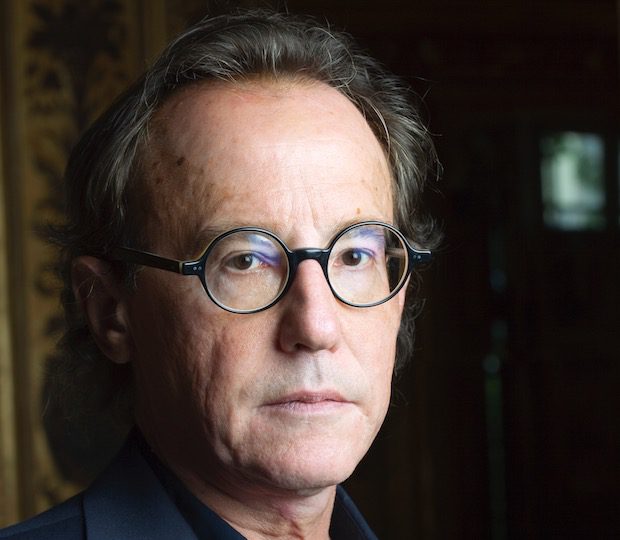

Donald Trump’s victory last November was a shattering event for American liberalism. Surveying the destruction, the liberal Columbia University humanities professor Mark Lilla wrote that “one of the many lessons of the recent presidential election campaign and its repugnant outcome is that the age of identity liberalism must be brought to an end.” When his essay arguing for that claim appeared in The New York Times, it caused controversy on the left, because it dared to question one of American liberalism’s most dogmatically held beliefs.

Lilla has turned that op-ed piece into a short book called The Once And Future Liberal: After Identity Politics, which appears in bookstores today. It’s a thin but punchy book by a self-described “frustrated liberal” for liberals. Lilla is tired of losing elections, and tired of watching his own side sabotage itself. In an e-mail exchange, Lilla answered a few questions I put to him about the book:

RD: You fault liberals for throwing themselves “into the movement politics of identity, losing a sense of what we share as citizens and what binds us as a nation.” Critics might argue that the period of US history that you praise — the “Roosevelt Dispensation” — was a time when blacks, women, gays and other minorities were oppressed. The contention is that the binding you seek to restore was only achieved by suppressing difference in unjust and intolerable ways. How do you respond?

ML: The conclusion simply doesn’t follow from the premise. The premise is correct: during this period blacks, women, gays, and other minorities were oppressed, and still are, though less so than in the past. But it does not follow that the oppression was achieved causally by suppressing difference. On the country: by setting moral standards of equality and solidarity liberals had weapons for criticizing such oppression and pushing this country to live up to its promise. We have learned from historian Ira Katznelson’s work about the subtle and not so subtle ways in which Dixiecrats succeeded in keeping African Americans from benefiting equally from the New Deal and even the Great Society. But now that we understand that, we can work to make sure it doesn’t happen again and that our programs cover all citizens simply by virtue of their citizenship. We want to abolish the racist difference.

In other words, to understand what ails this country you need to pay attention to difference. In order to fix what ails us you need to hold onto the universal democratic ideal. We and keep fighting until we can make it a reality.

It is very hard to make identitarians see this. They seem to prefer making a point to making a change. But politics is not a speech act and it does not take place in a seminar room. It is not about getting recognition for certain groups who have problems, it is about acquiring power to help them. Now, recognition is important in democratic societies and it is acquired through formal and informal education: what happens in the classroom, what we see on our television and movie screens, what we read. (Sesame Street played a huge role in making this a more tolerant country.) Social movements are important too, since they can change hearts and minds. But acquiring power in a democratic system means winning elections, and winning elections (especially given American federalism) means having to persuade a lot of people from different backgrounds in every corner of the country that they share something and can work together to build something.

One of your most important insights is that liberal politics, by becoming driven by identity, have largely ceased to be truly political, and have instead become effectively religious (“evangelical” is the word you use). Can you explain?

We are an evangelical people. How we ever got a reputation for practicality and common sense is a mystery historians will one day have to unravel. Facing up to problems, gauging their significance, gathering evidence, consulting with others, and testing out new approaches is not our thing. We much prefer to ignore problems until they become crises, undergo an inner conversion, write a gospel, preach it at the top of our lungs, cultivate disciples, demand repentance, predict the apocalypse, beat our plowshares into swords, and expect paradise as a reward. And we wonder why our system is dysfunctional…

Identity politics on the left was at first about large classes of people – African Americans, women – seeking to redress major historical wrongs by mobilizing and then working through our political institutions to secure their rights. It was about enfranchisement, a practical political goal reached by persuading others of the rightness of your cause. But by the 1980s this approach had given way to a pseudo-politics of self-regard and increasingly narrow self-definition. The new identity politics is expressive rather than persuasive. Even the slogans changed, from We shall overcome – a call to action – to I’m here, I’m queer – a call to nothing in particular. Identitarians became self-righteous, hypersensitive, denunciatory, and obsessed with trivial issues that have made them a national laughing stock (drawing up long lists of gender pronouns, condemning spaghetti and meatballs as cultural appropriation,…). This was politically disastrous and just played into the hands of Fox News.

What the new identitarians demand is more than mere recognition, though. They demand that you see this country exactly as they do, reach the same moral judgments about it, and confess your sins (which is what the word “privilege” is a secular euphemism for). The most recent books by Ta-Nahesi Coates and Michal Eric Dyson are quite explicit about this need for repentance. The subtitle of Dyson’s is A Sermon to White America. And the use of the term woke is a dead giveaway that we are in the mental universe of American evangelicalism not American politics.

There is a barbed, pithy phrase toward the end of your book: “Black Lives Matter is a textbook example of how not to build solidarity.” You make it clear that you don’t deny the existence of racism and police brutality, but you do fault BLM’s political tactics. Would you elaborate?

There is no denying that by publicizing and protesting police mistreatment of African-Americans the BLM movement mobilized people and delivered a wake-up call to every American with a conscience. But then the movement went on to use this mistreatment to build a general indictment of American society and its racial history, and all its law enforcement institutions, and to use Mau-Mau tactics to put down dissent and demand a confession of sins and public penitence (most spectacularly in a public confrontation with Hillary Clinton, of all people). Which, again, only played into the hands of the Republican right.

As soon as you cast an issue exclusively in terms of identity you invite your adversary to do the same. Those who play one race card should be prepared to be trumped by another, as we saw subtly and not so subtly in the 2016 presidential election.

But there’s another reason why this hectoring is politically counter-productive. It is hard to get people willing to confront an injustice if they do not identify in some way with those who suffer it. I am not a black male motorist and can never fully understand what it is like to be one. All the more reason, then, that I need some way to identify with him if I am going to be affected by his experience. The more the differences between us are emphasized, the less likely I will be to feel outrage at his mistreatment.

There is a reason why the leaders of the Civil Rights Movement did not talk about identity the way black activists do today, and it was not cowardice or a failure to be woke. The movement shamed America into action by consciously appealing to what we share, so that it became harder for white Americans to keep two sets of books, psychologically speaking: one for “Americans” and one for “Negroes.” That those leaders did not achieve complete success does not mean that they failed, nor does it prove that a different approach is now necessary. There is no other approach likely to succeed. Certainly not one that demands that white Americans confess their personal sins and agree in every case on what constitutes discrimination or racism today. In democratic politics it is suicidal to set the bar for agreement higher than necessary for winning adherents and elections.

Chris Arnade, I believe it was, once wrote that college has replaced the church in catechizing America. You contend that “liberalism’s prospects depend in no small measure on what happens in our institutions of higher education.” What do you mean?

Up until the Sixties, those active in liberal and progressive politics were drawn largely from the working class or farm communities, and were formed in local political clubs or on union-dominated shop floors. Today they are formed almost exclusively in our colleges and universities, as are members of the mainly liberal professions of law, journalism, and education. This was an important political change, reflecting a deep social one, as the knowledge economy came to dominate manufacturing and farming after the sixties. Now most liberals learn about politics on campuses that are largely detached socially and geographically from the rest of the country – and in particular from the sorts of people who once were the foundation of the Democratic Party. They have become petri dishes for the cultivation of cultural snobbery. This is not likely to change by itself. Which means that those of us concerned about the future of American liberalism need to understand and do something about what has happened there.

And what has happened is the institutionalization of an ideology that fetishizes our individual and group attachments, applauds self-absorption, and casts a shadow of suspicion over any invocation of a universal democratic we. It celebrates movement politics and disprizes political parties, which are machines for reaching consensus through compromise – and actually wielding power for those you care about. Republicans understand this, which is why for two generations they have dominated our political life by building from the bottom up.

“Democrats have daddy issues” you write. I’d like you to explain that briefly, but also talk about why you use pointed phrasing like that throughout your polemic. I think it’s funny, and makes The Once And Future Liberal more readable. But contemporary liberalism is not known for its absence of sanctimony when its own sacred cows are being gored.

I was referring to Democrats’ single minded focus on the presidency. Rather than face up to the need to get out into the heartland of the country and start winning congressional, state, and local races – which would mean engaging people unlike themselves and with some views they don’t share – they have convinced themselves that if they just win the presidency by getting a big turnout of their constituencies on the two coasts they can achieve their goals. They forget that Clinton and Obama were stymied at almost every turn by a recalcitrant Congress and Supreme Court, and that many of their policies were undone at the state level. They get Daddy elected and then complain and accuse him of betrayal if he can’t just make things happen magically. It’s childish.

As for my writing, maybe Buffon was right that le style c’est l’homme même [style is the man — RD]. I find that striking, pithy statements often force me to think than do elaborate arguments. And I like to provoke. I can’t bear American sanctimony, self-righteousness, and moral bullying. We are a fanatical people.

As a conservative reading The Once And Future Liberal, I kept thinking how valuable this book is for my side. You astutely point out that before he beat Hillary Clinton, Donald Trump trounced the GOP establishment. Republicans may hold the high ground in Washington today, but I see no evidence that the GOP is ready for the new “dispensation,” as you call the time we have entered. It’s all warmed-over, think-tank Reaganism. What lessons can conservatives learn from your book?

I hope not too many, and not until we get our house in order! But of course if Palin-Trumpism – we shouldn’t forget her role as Jane the Baptist – has taught us anything, it is that the country has a large stake in having two responsible parties that care about truth and evidence, accept the norms of democratic comportment, and devote themselves to ennobling the demos rather than catering to its worse qualities. Democrats won’t be able to achieve anything lasting if they don’t have responsible partners on the other side. So I don’t mind lending a hand.

I guess that if I were a reformist Republican the lessons I would draw from The Once and Future Liberal would be two. The first is to abandon dogmatic, anti-government libertarianism and learn to start speaking about the common good again. This is a country, a republic, not a campsite or a parking lot where we each stay in our assigned spots and share no common life or purpose. We not only have rights in relation to government and our fellow citizens, we have reciprocal duties toward them. The effectiveness, not the size, of government is what matters. We have a democratic one, fortunately. It is not an alien spaceship sucking out our brains and corrupting the young. Learn to use it, not demonize it.

The second would be to become reality based again. Reaganism may have been good for its time but it cannot address the problems that the country – and Republican voters – face today. What is happening to the American family? How are workers affected by our new capitalism? What kinds of services (i.e., maternity leave, worker retraining) and regulations (i.e., anti-trust) would actually help the economy perform better and benefit us all? What kind of educational system will make our workers more highly skilled and competitive (wrong answer: home schooling)? If you don’t believe me, simply read Ross Douthat and Reihan Salam’s classic The Grand New Party, which laid this all out brilliantly and persuasively a decade ago. It’s been sitting on shelves gathering dust all this time while the party has skidded down ring after ring of the Inferno. (A conservative publisher should bring out an updated version…) Or take a look at the reformicon public policy journal National Affairs.

Oh, and a bonus bit of advice: get off the tit of Fox News. Now. It rots the brain, makes you crazy, ruins your judgment, and turns the demos into a mob, not a people. Find a more centrist Republican billionaire to set up a good, reality based conservative network. And relegate that tree-necked palooka Sean Hannity to a job he’s suited for, like coaching junior high wrestling…

As you know, there is a lot of pessimistic talk now about the future of liberal democracy. There’s a striking line in your book: “What’s extraordinary — and appalling — about the past four decades of our history is that politics have been dominated by two ideologies that encourage and even celebrate the unmaking of citizens.” You’re talking about the individualism that has become central to our politics, both on the left and the right. I would say that our political consciousness has been and is being powerfully formed by individualism and consumerism — tectonic forces that work powerfully against any attempt to build solidarity. Another tectonic force is what Alasdair MacIntyre calls “emotivism” — the idea that feelings are a reliable guide to truth. Could it be the case that identity politics are the only kind of politics of solidarity possible in a culture formed by these pre-political forces?

It’s an interesting argument that, if I’m not mistaken, Ross Douthat has made in other terms. I can see that they might be gestures toward solidarity but real solidarity comes when you identity more fully with the group and make a commitment to it, parking your individuality for the moment. Identitarian liberals have a hard time doing that.

Take the acronym LGBTQ as an example. It’s been fascinating to see how this list of letters has grown as each subgroup calls for recognition, rather than people in the groups finally settling on a single word as a moniker – say “gay,” or “queer,” or whatever. I don’t see how ID politics makes solidarity possible. Instead it just feeds what I call in the book the Facebook model of identity, one in which I like groups temporarily identify with, and unlike them when I no longer do, or get bored, or just want to move on.

Here’s a last question — and forgive me, but it’s a long one. I’ve been reading the French novelist Michel Houellebecq lately, and have been struck by how darkly prophetic he is. Houellebecq is not a religious believer, but his novels explore the arid landscape of the post-Christian, materialist West (or at least France). Following Comte, Houellebecq thinks it’s impossible to bind a society together without religion of some kind. In this sense, identity politics may have to do with the demise of Christianity and its replacement by a de facto materialism built around worship of the Self and its desires. (I should say here that I agree with the sociologist of religion Christian Smith, who writes that American Christianity has been hollowed out and replaced by an ersatz, self-centered pseudo-religion he calls Moralistic Therapeutic Deism.) Louis Betty, an American scholar of French literature, from his study of the religious dimension of Houellebecq’s work. Betty observes that as religion (Christianity, specifically) loses its centrality to a society’s life, and becomes rather just another part of the whole, it dissolves. “This is simply not enough for modern people; the symbols therein are too weak, too uncoupled from ordinary existence to give serious motivation. Religion must set a disciplinary canopy over the head of humankind, must order its acts and its moral commitments, must furnish ultimate explanations capable of determining the remainder of social life; otherwise, religion loses itself in the morass of competing perspectives (scientific, commonsense, political, etc.) This is precisely what has happened in the West… .” I agree that the West has torn down the “disciplinary canopy” of the Christian religion. My question to you, assuming that you broadly agree with this judgment, is this: What comes next? What “strong god” will re-bind us? Offer a best-case scenario, and a worst-case one.

Now we’re getting to my last book, The Shipwrecked Mind: On Political Reaction. This is a subject I’ve thought a good deal about, and not only in relation to Houellebecq, who figures in Shipwrecked, so forgive me if I digress.

I don’t agree with your judgment, and here’s why: I have no faith in grand, apocalyptic historical narratives, any more than I have faith in optimistic progressive ones. The worry about the social consequences of abandoning religion are quite old. Just look at ancient Roman polemics against Christianity, which (besides being brilliantly funny sometime) revolved around the social effects of Jesus’s message, not its truth or falseness. Reform movements within Christianity itself have often rung the alarm about cultural decline, for reasons opposite of the Romans’: the Romans found Christianity unmanly and anti-civic, Christian reformers have found every new orthodoxy (most of which began in reform movements) a threat to the simple Christian life and the family.

But something in these polemics changed after the French Revolution, when the focus shifted from the goodness of the Christian life to how the course of history was destroying it. After the Revolution thinkers felt compelled not only to come to a judgment about “modernity” as a set of values but as a historical bloc, a geschichtliche Poltergeist [historical poltergeist — RD]. The anti-moderns started telling a story modelled on the Christian one – Abraham /Kairos / Jesus, lost soul / Kairos / saved soul – but with an apocalyptic conclusion: Christian paradise / Jacobin Kairos / modern inferno. All the variety and complications of the Christian era got airbrushed out, as did the variety and complications of the post-Christian one.

This kind of thinking drew thinkers into a kind of intellectual game, call it “pin the tail on the Kairos.” Crime in the streets? Blame Rousseau. Children speaking back to parents? Blame Voltaire. Kids on the internet? Blame the Encyclopédie. (See my chapter on Brad Gregory in Shipwrecked.)

It’s an intellectual trap. Yes, certain things precede others things; changes have consequences; etc. But history is not a thing, it is a story we tell ourselves as we try to make sense of past and present experience. It does not come divided into pre-cut eras; an “era” is just the space between two marks on a ticker tape that we ourselves draw in order to make sense of our experience. They are useful only so long as they explain things. An era does not have inner “spirit,” such that, if we understand it, we can both explain what has happened in it and, for the present age, predict what will come next. That’s magical thinking.

And it leads to questions like yours: what comes next? If period A was happy because of X, and period B is unhappy because it destroyed X, in period C won’t we have to either restore X or find a substitute for it? This was Comte’s idea and Houllebecq plays with it in his novels. (He never does more than play, which saves his writing.) But what if the picture is all wrong? What if, say, human nature is pretty much the same and that in different historical and social conditions certain qualities get exaggerated, and others wither. Once, say, in our society we were less tolerant but more charitable; today, the reverse. That’s not surprising, and thinking in this way forces you pay attention to both the benefits and costs of change. Yes, sometimes there are costs without benefits, but usually not in human affairs.

That’s not so say we aren’t obliged to choose how to live; we are, because we can. We don’t have to wait for a new apocalypse to overcome the effects of the last one. Certain anti-modern arguments take the form, “things just can’t go on like this.” But, as a sage once put it, if things “can’t go on” they won’t. And modern society does go on. Anti-modern critics need to recognize that: yes we can live in a world without religion structuring our relations, without a “sacred canopy,” etc. The only relevant question is whether it is a good way to live or not.

An example: I read Allan Bloom’s The Closing Of The American Mind while living in Rome, just after it came out. I started it on a lovely Sunday afternoon after I had just taken a walk in the park, where I saw kids dressed in punk and goth outfits (the Eighties!) strolling with their grandmothers who were dressed in widow’s black. It was not the old Catholic Italy, but it was still Italy. People were eating the same food, hanging out with large networks of friends, showing up late for everything. And the ship sailed on. So after my walk and a nice lunch on a sunny piazza I pick up Bloom and learn that the apocalypse has already happened, that we are surely doomed, that modernity destroys all virtue, that Woodstock was no different from Nuremberg, and other such nonsense. It was a liberating moment for me intellectually, and inoculated me forever against prophets of doom drunk on historical fables.

That does not mean the present is acceptable because it is where history has landed us. That, too, is a historicist trap. We still have to choose how to live. What I appreciate about The Benedict Option, stripped of historiological hocus-pocus, is that it makes an ultimate value judgment about certain ways of living, and urges people to withdraw and take control of their lives as best they can. We are always in a historical situation, but we can always choose how to live in the face of it, individually and collectively. Not everything is possible, but certainly everything is not so determined that Nur ein Gott kann uns retten [“Only a god can save us” — philosopher Martin Heidegger’s judgment on our time]. To choose is to live seriously, and I respect people who do that consciously and with full awareness of the consequences.

My prescription for anti-moderns is to up your dose of Sartre and stop taking those Hegel-Comte-MacIntyre pills. They don’t agree with you.

What should we learn about identity politics from the terrible events in Charlottesville?

First, obviously, is how inflammatory identity can be. I’m struck by the psychological parallels between the Charlottesville killer and the marginal types who are drawn to political Islamism in Europe. These kids tend to be loners, often from broken homes, who find in identitarianism what they think is an explanation of all their resentments, and a program for striking back. It gives them a purpose and a sense of belonging to something larger than themselves. And once they are sucked in, the logic of the ideology drives them relentlessly toward violence. The content of the ideology matters, in both cases. Political Islamism is about Islam (a perversion of it) and the racist alt-right is about the right (a perversion of American conservatism). We need to recognize both facts.

Second, for my side, the lesson should be that left identitarianism is a dead end. It does not unify anybody and it only plays into the hands of the alt-right by inflaming passions. We need to recognize that.

Third, for the conservative movement, the lesson is that you own this. Yes, you are horrified by what happened and you condemn it in no uncertain terms. But you have failed to police your side, you have sanctioned indifference to truth, fallen silent in the face of demagogues (Beck, Palin, Hannity, Trump), tolerated a horrifying internet subculture, demonized your opponents, and inflamed hysteria. By not attacking white nationalism you have abetted it. Just as moderate imams in Europe preferred not to see what was happening in their mosques, so you have been in denial about the environment you created. It is time to pluck the identity beam out of your own eye before complaining any more about left identity politics.

—

Mark Lilla’s new book The Once And Future Liberal: After Identity Politics is out today from Harper.