Looking Forward to Good Friday

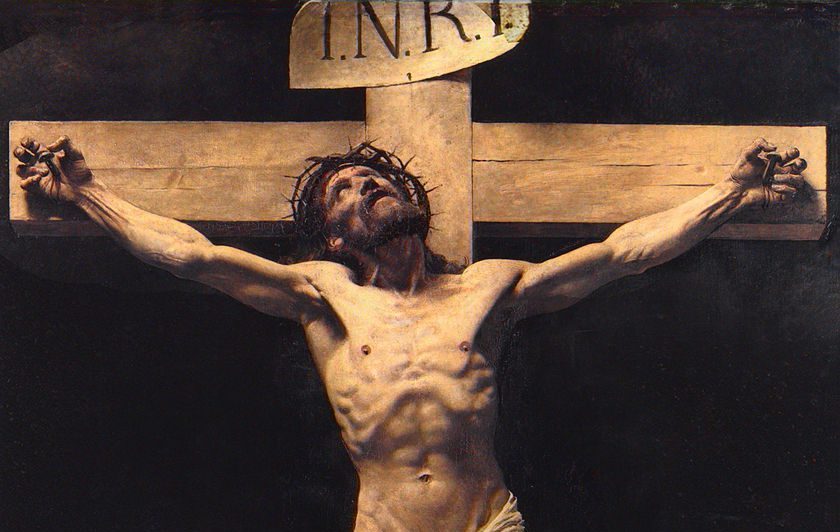

A columnist asked to say something of value about Good Friday finds himself in an almost uniquely unenviable position. Probably no series of occurrences has been the subject of more commentary (if that is the right word for it) than the one that began with the betrayal of a certain Roman non-citizen, who spent the last evening before his death in the company of that society of friends who would afterward comprise the rather crude and unlettered leadership of the religious sect he founded, and ended with an event that is arguably outside the scope of “history,” at least as it is conventionally understood.

Thank goodness, then, for the ignorance of Philip Pullman, the author of a series of more or less forgotten children’s books about magical polar bears, who recently unburdened himself of the following speculations:

If Jesus had been a Roman citizen, like Paul, he would have been beheaded and not crucified. How would the church have managed without 2000 years of cross-based iconography? Never mind a much greater difficulty with the resurrection.

— Philip Pullman (@PhilipPullman) April 10, 2022

It would be easy to mock Pullman for his ignorance of (for example) the precise reasons why Our Lord could only have been a Jew lacking the rights, such as they were, of the Roman citizenry. His stupidity shows us that by economy good can arise out of evil, which is, fundamentally, nothing but the temporary privation of the former, a contingent state of affairs whose persistence is a reminder that the whole of creation groans in anticipation of that final and irreversible undoing of an ancient alienation.

Besides, taken at face value, Pullman’s words suggest that (to reverse Blake’s famous dictum) he is of Christ’s party without knowing it. For he has intuited exactly what its enemies have always hated about the Christian religion, namely, the idea that the Savior of the world would not only condescend to His own judicial murder at the hands of a relatively minor provincial official, and that the execution in question would take place in the manner reserved for slaves and others outside the political community of the Roman imperium, with its supposedly glorious privileges, but that by His suffering he would bring about a revolution in which the values of classical civilization were destroyed forever: an exaltation of meekness, purity, even servility, a mood of resignation in the face of present injustices and iniquities that many spirits since (including that of this columnist) have found baffling and even despicable.

Earlier this week, I was taking two of my children to T-ball practice. Given the almost total collapse of our former national pastime, it should not be surprising that in my part of the world organized youth baseball has been relegated to what sociologists would refer to as a “low-income area.” There, standing in front of a subsidized apartment complex, was a girl, aged probably seven or eight, shoeless, in a men’s oversized T-shirt, patiently watching over her younger siblings. I could not have seen her for more than a few seconds, but in the days since I have found myself thinking of her. Her face conveyed an indescribable longing, an expression that can be found only on the faces of children, one that any parent will recognize. From the cold wet ground she seemed to expect the imminent arrival of some long-occluded power, some final and total reckoning with unseen forces, a victory that would come not with armies or the trappings of temporal power but (for her anyway) with an ineffable and unearthly joy already present in her face and those of the other children.

I mention all of this because what Pullman half-consciously intuits is a precise understanding of what makes Christianity so objectionable, a truth as radical today as it was 2,000 years ago. This is nothing less than its anticipation of the day when this girl and so many like her—the disabled, the “unhoused,” as we now put it, whom we walk past without acknowledging mentally or otherwise even the bare fact of their existence, the daughter of a dear friend of mine whose gestation and birth were greeted by medical professionals as a preventable evil—will inherit the earth and find themselves exalted above its princes. The principalities and powers will fall with the darkness by which they are surrounded, and those in high places will be sunk in the desolation of their wickedness. If that sounds terrible to Pullman, as it has for so many others before him, it is simply because it is terrible, in the old-fashioned sense of the word—terrible and, if we follow in the hopes of those impossibly crude persons whose weeping at the sight of a decidedly not beheaded body two millennia ago would soon give way to jubilation, true.

Comments