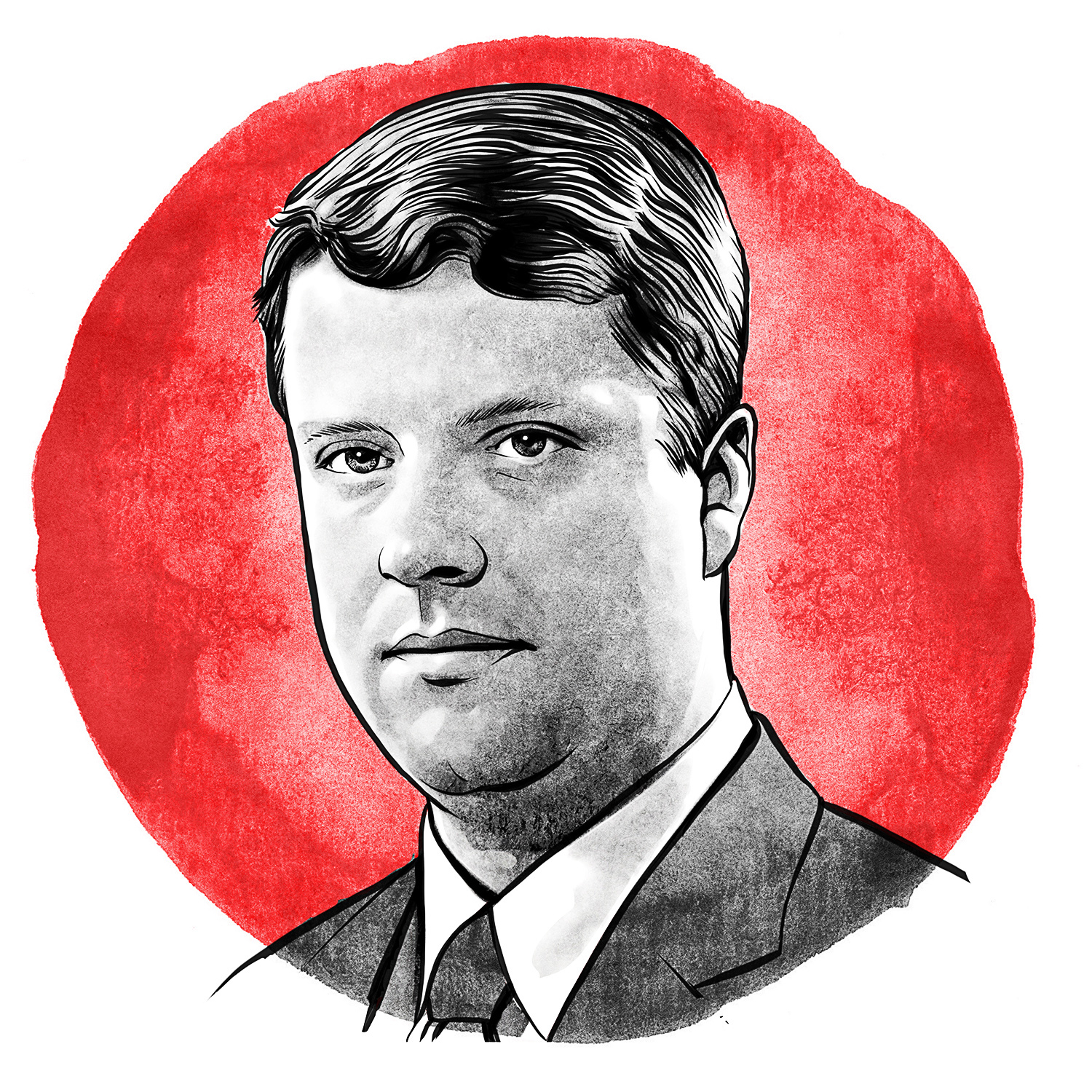

Liberty’s Maverick

Rep. Justin Amash sticks to the Constitution—even when it hurts.

The Washington Examiner calls him a “small government heartthrob.” The New York Times reports he has “voted against Republican-backed bills more than any other party member, even if he agrees with them.” Greta Van Susteren brands him “cowardly.”

The Washington Examiner calls him a “small government heartthrob.” The New York Times reports he has “voted against Republican-backed bills more than any other party member, even if he agrees with them.” Greta Van Susteren brands him “cowardly.”

People are talking about Rep. Justin Amash. The freshman Republican from Michigan rode the Tea Party tide to Congress last fall. At 31, he is the second-youngest member of the House. And at a time when Constitution-reading is once again in vogue among Republicans, Amash’s strict fidelity to the document sometimes unnerves members of his own party.

He’s a pro-life fiscal conservative who refused to vote for stripping National Public Radio and Planned Parenthood of taxpayer support. He’s a critic of foreign interventionism who nonetheless voted against ending the Afghan War. Six months into his congressional career, Amash is more of a maverick than John McCain ever was.

Consider his NPR vote. Republicans have never been fond of public radio, for reasons both principled (radio stations shouldn’t receive taxpayer subsidies) and political (public broadcasting leans left). In March, after a video sting operation by conservative activist James O’Keefe yielded embarrassing quotes from public radio executives, the new Republican-controlled House decided to try to defund NPR and the Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB).

The House passed the defunding bill by 228-192, but seven Republicans voted no and one voted present. The no votes came mostly from moderates or Republicans who represented swing districts, where constituents like their “All Things Considered,” thank you very much. But Amash’s “present” vote was a surprise—and in Van Susteren’s mind, an unpleasant one. That’s the vote that caused the Fox News anchor to accuse the congressman of being “rather cowardly” and disenfranchising his constituents. “Why are you there if you don’t vote?”

Others might wonder if Amash is just a contrarian, since the Gray Lady says he sometimes declines to vote for bills even when he agrees with them. The truly curious, however, can find a detailed explanation of his reasoning on the congressman’s Facebook page.

“H R 1076 does not actually save taxpayer dollars; it merely blocks CPB from exercising its discretion to send funding to NPR,” Amash posted. He objected that singling out one organization rather than broadly ending federal subsidies to broadcasters might be an unconstitutional bill of attainder. “Other private entities that are identical to NPR—except for their names—will continue to receive federal funding,” he explained. “Congress has singled out NPR not for any legitimate, objective reasons—such as, ‘taxpayers shouldn’t subsidize any speech’”; instead, “the legislation takes aim at one particular private entity” solely “because that entity is unpopular.”

“I want to defund NPR,” Amash concluded. “But I want to do it the right way, in accordance with the Rule of Law.” When Amash proposed an amendment that would end federal money for public broadcasting across the board and actually save taxpayer dollars, the House Rules Committee wouldn’t even let it come to a vote. This would not be the last time Amash’s colleagues put symbolism over slashing spending.

In April, House Republicans negotiated a deal with the Obama administration and Senate Democrats to avoid a government shutdown. The resulting resolution would fund the federal government for the next six months, the remainder of the 2011 fiscal year, while achieving what both sides touted as “historic” budget cuts of $38.5 billion. Amash wasn’t happy, but when the Congressional Budget Office reviewed the budget pact, the details proved to be worse than Amash suspected: the agreement would only shave $352 million off the current year’s deficit.

“Even $38 billion out of the $3.8 trillion is just not enough,” Amash says. “I’d prefer that the leadership not describe cuts like these as historic or substantial.” He was one of 59 Republicans to vote against the resolution. Less than a third of the Tea Party-infused freshman class, and not a quarter of the House Republican Conference, joined him. Later, he voted for both the Paul Ryan-crafted official Republican budget for 2012—“It’s a good start,” he says—and the more conservative Republican Study Committee alternative.

Amash was elected to Congress after a single term in the Michigan state legislature. He won a five-way House primary with 40 percent of the vote. Not everyone in the Republican Party was happy with the outcome: two daughters of his predecessor, GOP Rep. Vern Ehlers, threw their support behind the Democrat, a former Harvard classmate of Barack Obama’s, in the general election.

Amash campaigned as a hard-line fiscal conservative willing to tackle entitlement reform and opposed to bailouts. And more troubling to the party establishment, Amash describes himself as “generally noninterventionist” on foreign policy. He says the Iraq War was the “wrong fight.” Although he supported toppling the Taliban and going after Osama bin Laden, he opposes nation-building in Afghanistan and wants to pull the troops out. He believes President Obama should have consulted Congress before going into Libya—and that Congress should have said no.

“It is astonishing that the administration seems to think a U.N. resolution is required but a declaration from Congress is not required to initiate offensive military strikes,” he said at the beginning of the Libyan conflict. “No U.N. resolution and no press release from the Arab League can replace Congress’s authorization.”

The son of a Palestinian Christian who settled in Muskegon, Michigan, Amash says his father’s typical immigrant experience is what made him interested in serving his country through politics. He started out a more conventional Republican, and he remains an admirer of Ronald Reagan. In recent years, he has become more noninterventionist on foreign policy. But like most other Tea Party-backed Republicans, it is the national debt—now reaching crisis proportions—that most animates Amash’s political activity. “The debt crisis will hurt the middle and working class more than the wealthy by far,” he says.

These views won him the endorsement of Rep. Ron Paul (R-Texas) and have made Amash a hero to libertarian-leaning Republicans. Paul called Amash “one of the best young candidates” he had seen in a generation. Following his victory last November, Amash is now the most successful Ron Paul Republican who isn’t a member of the family. “Let me tell you,” Congressman Paul said in a statement after Amash arrived in Washington, “I have not been disappointed.”

Although he embraces the comparison, Amash isn’t exactly a Paul clone. His Capitol Hill office is decorated with photographs of Austrian economists whose explanations of the business cycle and free markets inform the congressman’s views of the economy. But when I spot what looks to be a picture of Murray Rothbard—the radical libertarian who was a key influence on Ron Paul—on the wall, Amash is quick to say, “I’m more Hayek than Rothbard.”

There are times when Amash is even stricter than the Texas congressman in his interpretation of the Constitution. Though he may agree with the policy behind a proposed piece of legislation, he will not support it unless he believes it is constitutional. In theory, this ought to please conservatives, especially those of the exacting, Constitution-reading variety. In practice, it has often angered and confused them, as Amash has declined to vote for bills that were good enough for Ron Paul.

Amash explains all his votes on Facebook. “I started doing that with budget votes in the state house,” he says. “Then I started doing it with all my votes, rather than explaining them in press releases or interviews with the media.” Amash is especially fond of showcasing the section of his page that clarifies his policy on voting present.

He takes this option in three circumstances. He will vote present when he supports the substance of a bill “but the legislation uses improper (e.g., unconstitutional) means to achieve its ends.” He’ll also do so when representatives haven’t been given enough time to reasonably consider the bill, or if he has a conflict of interest, “such as a personal or financial interest in the legislation.”

Amash says hasn’t seen a conflict of interest yet and doesn’t anticipate any coming up. He regularly votes present on approving the journal of the previous House sessions because members don’t get more than five minutes to review the journal. But it is the legislation that uses unconstitutional means to achieve ends with which he agrees that confounds the New York Times and causes the most controversy among his allies. The NPR vote hasn’t been the only example.

Amash also voted present on the Pence Amendment, which would have terminated all federal funding to Planned Parenthood. His logic was the same as with NPR: he felt the legislation singled out Planned Parenthood rather than addressing all organizations that perform or promote abortions. This arguably made the amendment a bill of attainder and therefore unconstitutional. Amash pointed out he supported a different bill denying Title X funds to all groups that perform abortions or refer women to abortion services. He is also a co-sponsor of the No Taxpayer Funding for Abortion Act.

Right to Life of Michigan wasn’t satisfied. “Both National Right to Life and Right to Life of Michigan are very concerned about this vote as it effectively was a ‘no’ vote,” a representative of the Michigan pro-life group wrote on their blog. The group recommended some responses to its supporters. “I believe he should have voted ‘yes’ even if Planned Parenthood was named in the bill,” read one. “I feel his vote of ‘present’ was a missed opportunity to stand up for the unborn despite his explanation as a rule of law,” said another.

Those were the most polite suggested responses. The last one was much tougher. “I want to register my displeasure with Rep. Amash’s vote on the Pence Amendment to de-fund Planned Parenthood,” it read. “I feel his explanation is a feeble attempt to justify a vote against denying funds for the largest abortion provider in the country.” Amash’s office heard from numerous disappointed Right to Life supporters.

Then there was the Nadler Amendment, which purported to fund a swift withdrawal from Afghanistan. Amash voted against it. He later voted present on a nonbinding withdrawal resolution by Rep. Dennis Kucinich (D-Ohio). “In the tenth year of a ridiculous, illegal, and completely counterproductive war of aggression,” complained libertarian writer Anthony Gregory, “Justin Amash, a Michigan freshman Congressman with some libertarian leanings whom I was told to keep an eye on, joined the 97 percent of his party in the House voting against a completely reasonable and moderate plan to withdraw troops from Afghanistan.” Gregory called it another “epic fail from the Tea Party.”

Amash says that in both cases his problem wasn’t with the underlying policy of withdrawing from Afghanistan, but with the means that would be used to do so. The first amendment “cut funding to a level that Rep. Nadler (D-N.Y.) claimed would allow for safe withdrawal.” Amash said he needed something more than Nadler’s assertions to know if the funding level would truly achieve that result. Meanwhile, Kucinich’s proposal relied on the “legislative veto” in the War Powers Resolution, which Amash deems unconstitutional. Amash has introduced his own bill calling for withdrawal from Afghanistan. He has also sponsored legislation to halt U.S. air strikes against Libya.

Amash says that in both cases his problem wasn’t with the underlying policy of withdrawing from Afghanistan, but with the means that would be used to do so. The first amendment “cut funding to a level that Rep. Nadler (D-N.Y.) claimed would allow for safe withdrawal.” Amash said he needed something more than Nadler’s assertions to know if the funding level would truly achieve that result. Meanwhile, Kucinich’s proposal relied on the “legislative veto” in the War Powers Resolution, which Amash deems unconstitutional. Amash has introduced his own bill calling for withdrawal from Afghanistan. He has also sponsored legislation to halt U.S. air strikes against Libya.

Amash’s reading of the Constitution isn’t always shared by other constitutionalists. Ron Paul voted for both the Nadler Amendment and the NPR de-funding; he is a co-sponsor of the Pence Amendment. “I think [Amash] makes a mistake by accepting the premise that individual groups have some kind of right to federal money and that barring them is constitutionally dubious,” journalist David Freddoso wrote after the Planned Parenthood vote. “No such right exists, and the Second Circuit Appeals Court ruled on the latter issue this last year when it upheld the ACORN defunding provision.”

But most strict constitutionalists agree that members of Congress have an obligation to make their own independent judgments about the constitutionality of legislation and then vote accordingly. In a way, that makes Amash an interesting test case. Although they frequently invoke the Constitution, do social conservatives and libertarians—and, for that matter, Tea Party sympathizers and Ron Paul supporters—really want legislators who will vote against their preferred policies on procedural grounds? Or at the end of the day, do the results—whether getting out of Afghanistan or defunding Planned Parenthood—really matter more?

Amash believes that fidelity to the Constitution will ultimately deliver his supporters the results they want. And he has his admirers. “I get my daily civics lesson with his Facebook updates,” says libertarian Republican activist Corie Whalen. Perhaps Amash’s colleagues in Congress should do so as well.

W. James Antle III is associate editor of The American Spectator.