Latin America’s Rightward Turn Continues in Costa Rica

Voters are looking for solutions to crime and disorder.

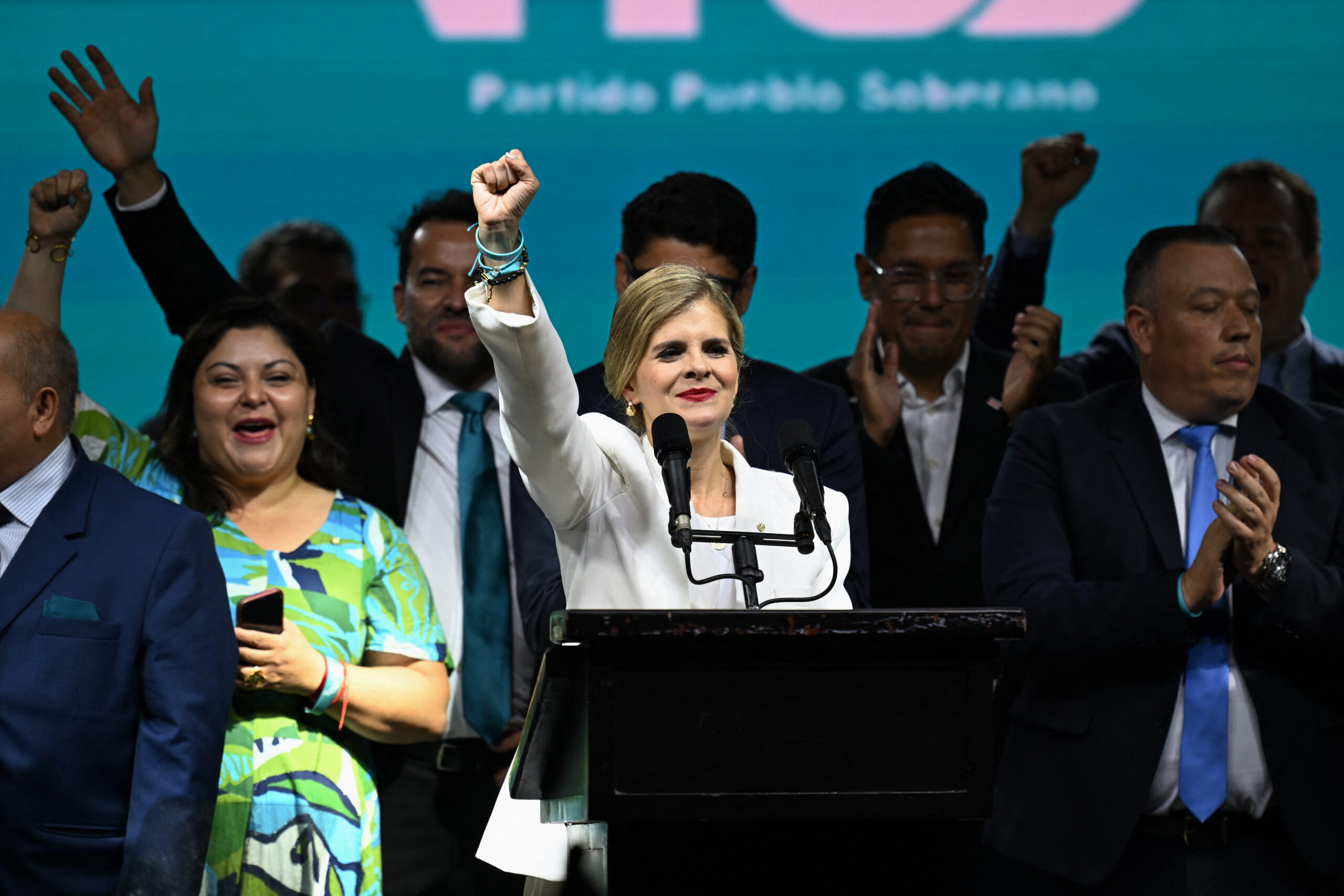

Costa Rican voters went to the polls earlier this month, handing a major victory to right-wing presidential candidate Laura Fernández in the first round. Fernández, the hand-picked successor of current Costa Rican president Rodrigo Chaves, handily won a plurality in the presidential contest, taking 48 percent of the vote. Her closest competitor, Álvaro Ramos, of the left-wing National Liberation Party, collected just 33 percent of votes.

The results secured Fernández’s victory in the first round without the need to proceed to a runoff election, the usual process if no candidate surpasses 40 percent of the vote. It also handed her control of the legislature, with her Sovereign People’s Party obtaining 31 of the 59 seats in Costa Rica’s legislature—a benefit her predecessor Chaves did not have.

Chaves, like Argentina’s President Javier Milei, was an upstart anti-establishment politician whose victory in 2022 came as a shock to experts and political commentators. A populist who railed against Costa Rica’s established institutions and maintained a Trumpian disdain for journalists and the media, Chaves was controversial among the Costa Rican elite but proved enduringly popular with the people at large.

The outstanding development of Chaves’s presidency was a major crime wave that has troubled the country since shortly after his election. The situation has shocked the populace: For decades, Costa Rica was seen as an exception to the challenges that have traditionally troubled Latin American countries—crime, corruption, and poverty were all relatively low, and the country maintained a robust economy, education system, and welfare state. The country abolished its standing army in 1949, and its commitment to ecological preservation has given it a reputation as a stable, idyllic oasis in a region bedevilled by poorly functioning societies. That illusion has now evaporated: In 2023, the country hit a record-high homicide rate, and is now more dangerous than Guatemala and Panama. Petty crimes like assault and robbery have increased as well.

The increase in criminality has been driven by the rapidly expanding presence of organized crime in the country. In 2023, Security Minister Mario Zamora stated that the number of criminal organisations in Costa Rica had ballooned from 35 to 340 over the previous decade; that number has continued to grow in the years since. Cartels looking to establish lucrative overland routes through the country have made inroads into the cities and led to increased concerns about corruption and the subversion of government officials. Unused to dealing with such threats, the national police were caught on the back foot.

Chaves’s response has been to attempt a major crackdown on crime, taking a page from El Salvador’s President Nayib Bukele, who has become a major regional ally. Last year, Chaves pushed through a constitutional amendment to allow the extradition of Costa Ricans accused of drug trafficking or terrorism. The country is in the process of conducting its first-ever extradition, sending two men (including a former judge) to the U.S. to be put on trial for cocaine trafficking. Chaves also began revamping the prison system. In January, Bukele flew in to attend the ceremonial groundbreaking of a new supermax prison inspired by El Salvador’s Terrorism Confinement Center (CECOT).

During his presidency, however, Chaves’s ability to institute mano dura anti-crime measures was hampered by conflicts with the courts and with the legislature, which was controlled by opposition parties. That will not be the case for Fernández, who has pledged to use her new legislative majority to continue Chaves’s crackdown and reform the country’s court system.

Fernández’s victory in Costa Rica is another illustration of the continuing tilt to the right in Latin America, which has seen the left-leaning governments of the Pink Tide fall under popular discontent with migration, crime, and public order. With the addition of José Antonio Kast in Chile and Nasry Asfura in Honduras, nine Latin American countries will be governed by right-wing parties, and that number is certain to increase. After the disastrous governments of Pedro Castillo (who was impeached and made a pathetic and quickly aborted attempt at a self-coup) and his successor Dina Boluarte, whose approval ratings sunk into the low single digits, Peru is disgusted with the left. Both front-runners for the country’s April presidential election are on the right. Colombia, where President Gustavo Petro’s government has been racked by scandal and the collapse of his attempted negotiations with the country’s endemic rebel groups, also appears likely to elect a right-wing government this May.

The new Latin American right has been bolstered by the successes of Bukele in El Salvador and Javier Milei in Argentina, as well as the support of President Donald Trump in the U.S., whose administration views right-wing Latin American governments as more reliable partners in its fight against drug trafficking and illegal immigration. But much of its success owes to the failures of previous left-wing governments, who have been reticent to respond to the growing influence of organized crime or popular frustrations with illegal immigration (especially from Venezuela).

Subscribe Today

Get daily emails in your inbox

The Trump administration is hoping to capitalize on the emerging right-wing Latin American bloc to further U.S. interests in the hemisphere. This week, new reports disclosed that the administration will be holding a Latin America summit in Miami next month; the guest list is expected to be made up exclusively of conservative and right-wing leaders friendly to the U.S., including Milei, Bukele, Asfura, President Rodrigo Paz of Bolivia, President Daniel Noboa of Ecuador, and President Santiago Peña of Paraguay, among others.

A cohesive and cooperative Latin American right would be a boon to the region, especially for combating drug cartels and other organized crime, whose large transnational networks are difficult for smaller countries in particular to effectively dismantle. Coordinating Latin American drug trafficking efforts is a role for which the U.S. is naturally fitted, and increased integration will augment existing American operations in the region.

Such contributions are desperately needed in Latin America, which continues to face seemingly intractable problems in civic and economic development. Corruption, poverty, poor economic growth, and organized crime have eluded attempts by governments right and left to bring countries in the region up to the standard of European nations, and despite having a head start in the 20th century the quality of life of the average citizen in Latin America has fallen far behind that of East Asia—a persistent driver of immigration legal and illegal to the United States.