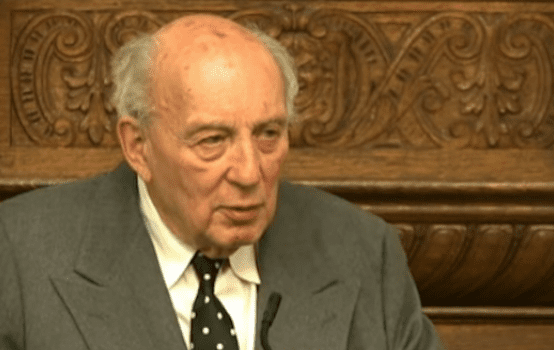

John Lukacs: Iconoclast and Self-Styled ‘Reactionary’

On May 6—just two days short of V-E Day, as he surely would have noted—we lost our nation’s greatest living historian of modern Europe. The Hungarian-born John Lukacs had for some time suffered from congestive heart failure. He died in his home in Phoenixville, Pennsylvania, at the age of 95.

As a young émigré scholar, Lukacs published his first book, The Great Powers and Eastern Europe (1953), at the age of 29. He quickly went on not only to write provocative studies of World War II and the Cold War, but also several biographical portraits featuring the two dominant figures of 20th-century Europe, Winston Churchill and Adolf Hitler.

Drawing on his talents as a narrative historian with an almost cinematic feel for pacing and character development, Lukacs repeatedly cast this pair in starring roles as his dueling dramatis personae, the war’s titanic hero faced off against his diabolical nemesis. Lukacs’ most famous book, Five Days in London, May 1940 (1999), in which he portrayed Churchill’s heroic resolve to forswear surrender to Hitler’s Germany during the Dunkirk crisis, was brandished in September 2001 by then-mayor Rudy Giulani as a story comparable to that of his intrepid fellow New Yorkers in the aftermath of 9/11. (Five Days in London was also the chief literary source for 2017’s The Darkest Hour, in which Gary Oldman captured an Oscar for his portrayal of Churchill.)

Lukacs’ international distinction as a scholar of 20th-century Europe has been widely honored in recent weeks. Ultimately, I believe he will rank as a historian alongside such towering 19th-century European predecessors as Jakob Burckhardt and Johan Huizinga. Less well known than Lukacs the eminent historian and outspoken public intellectual, however, was Lukacs the man and teacher, and a word here about those aspects of him is apposite.

Yes, he wrote provocative, challenging books. But “provocative” and “challenging” are also the words that come to mind when describing the generations of students whom he taught. I met him as a college sophomore at La Salle College (now University) in 1976, after hearing at length about him from his protégé and young colleague in the history department, John Rossi, who was already his dear friend. Lukacs put on no airs with his students, either inside the classroom or in conversation. It was only thanks to my conversations with Rossi that I had some awareness of his stature, the richness of his intellect, and the lived experience behind his words.

As always, Lukacs taught an advanced seminar in European history on a topic of his choosing. That semester, the topic was the opening phase of the war, covering the years before Pearl Harbor, with its main text Lukacs’ own The Last European War: 1939-1941. The class never discussed the book per se; it simply filled the air, as Lukacs riffed and ranted on its themes. And whatever the syllabus might have specified about the assigned reading or historical event for a given day, a class hour was always “Lukacs” in all his glory.

Unbuttoned, engaging, utterly original and inimitable, Lukacs made no attempt to “introduce” us ingenuous working- and lower-class youngsters fresh from the Philadelphia parochial schools to European politics and interwar issues. You took a Lukacs course for one reason: Lukacs. And that meant the chance to experience history filtered through the mind and personality of a world-renowned historian who hailed from a different world and had lived through the storied events on which he discoursed.

Janos Adalbert Lukacs was born on January 31, 1924. It struck me recently that, in one of his last books, he dedicated a chapter to “The Year 1924,” arguing that it was the most important year in 20th-century history. Lenin died on January 21 and Woodrow Wilson followed two weeks later on February 3. No mention is made of the author’s birth, yet this reader at least intuited that the Hungarian newborn Lukacs, sandwiched between the Russian and the American both in time and space, is the implied witness and custodian of the century’s fortunes, the cultural diagnostician who would go on to tell the dramatic story (culminating in the December 10 release from prison, with Mein Kampf in hand, of Adolf Hitler) that “1924” unleashed.

Lukacs’ father was a Catholic doctor. His mother, a Jew, converted to Catholicism and raised the boy as a devout Catholic. When Lukacs was eight years old, his parents divorced. His Anglophile mother imbued him with her ardor for England, where he attended summer school in his teens and deepened what he called his lifelong love affair with English culture and the English language (and began to entertain the knightly notion that he would somehow serve this demanding mistress, English, in later years).

Back home during the war years, Lukacs was classified by the invading Nazi forces in 1944 as a Jew. He was sent to a work camp, where he survived until the war’s end. He never re-established contact with a single relative. Presumably they all perished in the chaos of the war’s ending—or in the Holocaust.

Lukacs never harbored any illusions about Soviet “liberators” or the prospects for a communist Hungary. Orphaned with no means of support except his own wits and drive, he exploited his two great resources: his powerful intellect and his linguistic skill with English. He moved immediately to complete a Ph.D. in history at the University of Budapest in 1946 and to befriend American military authorities. With their help, only weeks after getting his degree, he set sail for New York, landing in July 1946. (Fittingly enough, as if it had spurred his departure, his hero Winston Churchill had recently delivered his famous “Iron Curtain” speech in Fulton, Missouri.) Taking advantage of the G.I. Bill’s educational benefits, returning soldiers were beginning to flood American universities. Within a year of his arrival, Lukacs secured a full-time position at Chestnut Hill College, a small Catholic women’s school in Philadelphia. He remained there happily until his retirement in 1994, commuting two days a week to teach his regular seminar at nearby La Salle.

Lukacs occasionally taught at prestigious universities for a semester (including Princeton, Johns Hopkins, the Fletcher School at Tufts, and the University of Pennsylvania). But “name” schools and fancy titles meant nothing to him. Yes, he had bothered to acquire the academic “union card” (a Ph.D.) as a 22-year-old, but that was just because he knew it would serve as a reliable meal ticket once he arrived in the United States. Few things aroused his contempt more than careerist professors, whom he scorned as academic hustlers.

Although some aspects of Lukacs’ thought—especially regarding religious matters, family issues, and the value of tradition—bore strong affinities to cultural conservatism, Lukacs was a fellow traveler, not a joiner. He was much admired in later years by some paleoconservatives, but he made no secret of his contempt for “the populist Right.” Populism and nationalism were his bogeymen, and he condemned these evil twins however and wherever they raised their heads, whether as newly emerging Hitlers or Huey Longs.

A maverick and iconoclast by both temperament and choice, he defied categorization ideologically, proudly calling himself a “reactionary.” That badge, he seemed to say, will keep the claimants at a distance. (“The Lettered Reactionary” served as the title of a portrait of him that I co-wrote with John Rossi for The American Conservative almost a decade ago. His choice of the term “reactionary” typified Lukacs, who was always delighted when his self-branding provoked a rise, or even caused a mild shock.)

Intellectual nonpareil, historian sui generis, Lukacs was always defiantly and gloriously his own man. Far from being a “don’t rock the boat” team player, he was completely unafraid to cut ties with his literary outlets (National Review and The American Spectator) and one-time benefactors, even if they were powerful gatekeepers and opinion-makers like William F. Buckley and R. Emmett Tyrell Jr.

Lukacs’ own intellectual integrity was high and inseparable from his moral integrity. Frequently dismissed by the academic elite as a mere “storyteller” and by the liberal intelligentsia as a curmudgeon, he placed his faith in the test of time, calmly self-assured that he would prevail with the only judges that mattered: his readers. That conviction fit well not only with his “reactionary” temper and love of the past, but also with his trust in the future as a Catholic believer.

“By having tried to render my work as an UNBOOK,” he once wrote to the editor of a history journal who not only failed to commission a review of a Lukacs’ tome but even to list it in an annual bibliography, “you have not succeeded in making me an UNPERSON.”

No indeed. And that failure was his readers’—and his students’—gain.

“Professor” Lukacs, requiescat in pace.

John Rodden has taught at the University of Virginia and the University of Texas at Austin. He has published 17 books, including George Orwell: The Politics of Literary Reputation.