In Defense of the Adventure Novel

The works of Robert Louis Stevenson and Rider Haggard should not be dismissed as tales for boys.

Before there was Caitlyn Jenner, before there was Rachel Levine, before there was Lia Thomas, there was Ernest Hemingway.

Within his own lifetime, Papa became an icon of American manhood. He fought in World War I (kind of) and the Spanish Civil War (not really). He went deep-sea fishing in the Caribbean and big-game hunting in Africa. He bedded women on every continent except Antarctica (probably). He moved to Cuba and smoked cigars with Castro. Other hobbies included boxing, drinking, and getting divorced.

In July of 1961, Papa curled his big toe around the trigger of a shotgun. Folks might have thought it was unseemly, but hardly out of character. Hemingway died the way he lived: on his own terms.

Then, in 1986, a new posthumous novel appeared. It’s called The Garden of Eden, and it’s shocking. An American writer named David Bourne is honeymooning with his new wife, Catherine, in the French Riviera. Shortly after arriving, Catherine cuts her hair “short as a boy’s” and dyes it blonde. “Don’t call me girl,” Catherine pleads with her husband. Eventually, she convinces him to cut and dye his hair the same way. “You are changing,” she coos. “Oh you are. You are. Yes you are and you’re my girl Catherine.”

It’s even stranger when we learn that Hemingway and his wife Mary also got matching haircuts and bleach jobs. Ernest called her Pete; she called him Catherine.

Was Hemingway transgendered? Probably not—at least, not in the modern sense. More likely he was succumbing to late-stage decadence. Like most modern writers, he suffered from two fatal flaws: sensualism and egotism. He was obsessed with himself and his own stimulation. Ultimately, he turned to crossdressing for his jollies. What else was left?

Seedy nihilism is the usual mood of modern literature. Why? Because, in order to get any serious critical attention, a novel must be “psychological.” And whose psyche should it reflect? The self-obsessed, angst-ridden literati, of course. Most new books aren’t worth the cost of paper. There’s a total disconnect with the experiences, beliefs, and tastes of normal people.

So, what’s the common man to do? Where can the ordinary bibliophile turn without being assaulted by all the kinks and broodings of our decadent elite? I suggest he start with the adventure novel.

Once upon a time, great authors were loved by their countrymen. They didn’t write 250 pages about drinking gin while a swarthy Italian sleeps with your wife. They talked about Barbary pirates, Scottish rebels, and Indian bandits. They filled their stories with gorgeous descriptions of faraway lands. There was plenty of action but no gratuitous violence. They were thoughtful—even philosophical, in their own way. But their worldview was basically the same as their readers’. They didn’t consider it their duty to shock or enlighten the public. They were the public. They were citizen-authors. And the fact that their books have vanished in favor of pompous trash like Ulysses or Sons and Lovers is a crying shame.

Every adventure novel is a blood descendant of Robinson Crusoe (1719). Its author, Daniel Defoe, was a fanatic. Born and raised Presbyterian, he threw himself into the religious controversies that followed the Glorious Revolution. In 1702 he published an anonymous essay called The Shortest Way with the Dissenters. Posing as an Anglican stalwart, he argued that the government should simply exterminate radical Protestants. The Shortest Way briefly captured the imagination of the Anglican establishment until its true authorship was discovered. Defoe was sent to jail, essentially for embarrassing the elites. Most gratuitously, he was sentenced to three days in the pillory.

Yet, he turned this humiliation into a triumph. His supporters rallied around him, reciting a long poem he’d written for the occasion called Hymn to the Pillory. It begins:

Sometimes the air of scandal to maintain,

Villains look from thy lofty loops in vain;

But who can judge of crimes by punishment,

Where parties rule, and law’s subservient?

Instead of being pelted with rotten produce, as was customary, Defoe was sprinkled with fresh flowers. After his release, he worked for Whig governments as a propagandist and occasional spy. It wasn’t until Defoe was nearly sixty that he turned to prose fiction. His first novel was his masterpiece, Robinson Crusoe.

The beginning and the end are a gripping, fast-paced tale of a young adventurer in search of excitement. He’s shipwrecked for the first time, enslaved by Moors, and escapes by sailing down the coast of Africa with an Arab slave-boy named Xury. He’s rescued by a Portuguese ship and sells Xury back into slavery. It’s all right, though. Xury didn’t mind. As Robinson explains: “I was very loth to sell the poor boy’s liberty, who had assisted me so faithfully in procuring my own. However, when I let him know my reason, he owned it to be just.” Robinson uses the proceeds to buy a plantation in Brazil before setting out on another voyage. He’s shipwrecked again, this time on a tropical island. That’s the beginning.

Towards the end, he discovers Carib tribesmen visiting the island to hold a cannibal feast. He saves one of these Caribs from being eaten; the Carib pledges himself to Robinson, who calls him “my man Friday.” Eventually they come across an English captain being marooned by mutineers on his island. Robinson and Friday help the captain to reclaim his ship. The grateful captain brings them to Europe, and Robinson and Friday fight off a pack of wolves in the Pyrenees on their way back to England.

Yet this is only about one-fifth of the book. The whole middle section, which makes up about twenty-eight years of Robinson’s life, isn’t quite so action-packed. He recounts, in painstaking detail, his efforts to survive on this island.

In the age of Amazon Prime, this aspect of the novel can seem quite dull. We’re not really interested in how he built his fortified roundhouse, or how he grew a field of corn from a few dried-up kernels he found among the flotsam. But to readers in the 18th century, it was part of the excitement. Maybe their attention spans were longer. Maybe they were more accustomed to working with their hands. In any event, Robinson Crusoe was an instant bestseller, going through four editions in the first year. It remained a staple of the common man’s library well into the 20th century.

The book is also quite didactic. Defoe, of course, isn’t shy about his religious views. Robinson spends an extraordinary amount of time beating his chest and weeping for his sins. Happily, he also converts Friday to Christianity. When Robinson asks what his man will do if he returns to his tribe—“Would you turn wild again, eat men’s flesh again, and be as savage as you were before?”—the Carib insists that he will be good: “Friday tell them to live good, tell them to pray God; tell them to eat cornbread, cattle-flesh, milk, no eat man again.”

Defoe had plenty of imitators, who are lumped together in a genre known as “Robinsonade.” The Swiss Family Robinson is probably the best-known. But new generations of writers took the adventure novel and made it their own. Chief among them, no doubt, is Jules Verne.

Verne’s novels fall into two categories. The first are those that imitate the heavily technical aspects of Robinson Crusoe, capturing the reading public’s interest in science and engineering. Most prominent among these is Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea (1870). For those who’ve only seen the excellent film starring Kirk Douglas, the novel itself can be jarring. Most of the book is given over to musings on nautical engineering. Captain Nemo explains how he takes everything he needs from the sea, including a nicotinic seaweed that he smokes in lieu of tobacco.

For modern audiences, Twenty Thousand Leagues can feel a bit Epcotish. So can its sequel, The Mysterious Island (1874). But to his contemporaries, electric-powered submarines were no more plausible than hovercars. Millions of ordinary men, women, and children devoured Verne’s books. They gushed over his strange technologies the way sci-fi nerds today argue about whether Qui-Gon Jinn’s lightsaber could really melt through the blast door in The Phantom Menace. That’s why Verne is known today as the father of science fiction.

But for those who can’t quite get into the Nemo stories, Verne wrote plenty of novels that are heavy on the action and light on the gadgets. The finest is Around the World in Eighty Days. It stars Phileas Fogg, a British aristocrat with a name only a Frenchman would think of. Fogg is a silent man of precise habits; once he fired a valet because the water for his morning shave was five degrees too cool.

One evening, while playing whist at the club, his friend reads an article in the Daily Telegraph calculating that it would take no fewer than eighty days to circumnavigate the globe. The unflappable Fogg wagers twenty thousand pounds—about £2 million today—that he can accomplish the feat in eighty days exactly. His friends are agog. “Twenty thousand pounds!” his friend cries. “Twenty thousand pounds, which you would lose by a single accidental delay!”

“The unforeseen does not exist,” Fogg replies cooly.

Along the way, Fogg and his new French valet, Passepartout, ride elephants in India. They eat a strange fruit called a banana (“as healthy as bread and as succulent as cream”). They save a beautiful widow from being burned alive in a suttee ritual by devotees of the bloody god Juggernaut. They’re chased across the Pacific by a British police officer with the unlikely name of Fix, who wrongly suspects Fogg of being a bank robber.

Eventually, Passepartout and Fix come to blows. For my money, it's the best fight scene in all of literature:

Passepartout, without a word, made a rush for Fix, grasped him by the throat, and, much to the amusement of a group of Americans, who immediately began to bet on him, administered to the detective a perfect volley of blows, which proved the great superiority of French over English pugilistic skill.

When Passepartout had finished, he found himself relieved and comforted. Fix got up in a somewhat rumpled condition, and, looking at his adversary, coldly said, “Have you done?”

“For this time—yes.”

Crossing the United States, Fogg is challenged to duel an American army colonel on a moving train. The conductor politely evacuates the car, but the train is attacked by the Sioux before they can start shooting. I won’t spoil the ending, except to say that there are no hot-air balloons. For that, you might try Five Weeks in a Balloon (1863), though Journey to the Center of the Earth (1864) is much better.

Verne’s most famous disciple is no doubt Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. His novella The Lost World (1912) is closely modeled on Verne’s Journey. Yet some of the later Sherlock Holmes stories have strong science-fictional elements, too. There’s “The Adventure of the Creeping Man” (1923), where an elderly professor tries to restore his sexual potency by injecting himself with a serum made from monkey glands, transforming himself into an apelike monster. It’s not one of his best.

After Conan Doyle, the adventure novel and science fiction largely become two separate genres. Practitioners of the pure, unadulterated adventure novel are mostly followers of Robert Louis Stevenson.

Stevenson’s best-known adventure tale is Treasure Island (1883), a picturesque story of pirates and castaways. It’s called a boy’s book, which only means there’s no cuckoldry or existentialism. There’s love, murder, greed, and treason; young master Hawkins shoots a pirate at point-blank range and watches his body sink into the shallow tide. But there’s no transvestites.

If anyone makes light of Stevenson’s genius, point them to Ransome, the cabin boy from Kidnapped (1886). The boy has been at sea since he was nine, working on the Covenant. He’s been on that evil ship for so long he’s forgotten how old he is. The narrator, David Balfour, recounts how the boy idolized his wicked captain, Hoseason. The skipper is “rough, unscrupulous, and brutal; and all this my poor cabin-boy has taught himself to admire as something seamanlike and manly.” His sad, strange life leaves him with a face twisted “between tears and laughter.”

Ransome is killed by the first mate, Mr. Shaun, in a drunken rage. His death is one of the saddest in all literature: “Even as he spoke, two seamen appeared in the scuttle, carrying Ransome in their arms; and the ship at that moment giving a great sheer into the sea, and the lantern swinging, the light fell direct on the boy’s face. It was as white as wax, and had a look upon it like a dreadful smile.”

Later, there’s a mutiny on board. Mr. Shaun is stabbed in the chest with a sword, says Balfour, and “passed where I dared not follow him.”

This is an element of the genre that Verne neglects but Stevenson places at the heart of his novels: the high moralism. Treasure Island and Kidnapped, like Robinson Crusoe, are about the triumph of good over evil. Honorable, upright characters always come through in the end. Killers, cowards, and drunkards always get their just deserts.

For both Defoe and Stevenson, the most common source of corruption is the docks. When Robinson first puts out to sea and is afraid of being drowned in a storm, he begs God to have mercy. But he’s scorned by his mates, who urge him to drown his fear in booze. So that’s what they do: “We went the old way of all sailors; the punch was made, and I was made drunk with it, and in that one night’s wickedness I drowned all my repentance, all my reflections upon my past conduct, and all my resolutions for my future.”

No doubt this is how Ransome became an alcoholic at the ripe old age of ten. Balfour sadly recounts all the nonsense that poor cabin-boy’s mates put into his head. They told him that dry land is “a place where lads were put to some kind of slavery called a trade, and where apprentices were continually lashed and clapped into foul prisons. In a town, he thought every second person a decoy, and every third house a place in which seamen would be drugged and murdered.” All the better to keep him on the Covenant so he could be drugged and murdered by Mr. Shaun.

Henry James was right when he said his friend Stevenson was “an artist accomplished even to sophistication, whose constant theme is the unsophisticated.” But while the adventure novel may be popular, it certainly wasn’t populist. Its heroes are natural aristocrats: men of ordinary stock whose quick wits and sound morals see them through great adventures, of which their neighbors could only dream. They usually wind up making quite a lot of money, too.

The adventure novelists of Stevenson’s generation also embraced a kind of reactionary romanticism. Robert Louis himself clearly had a soft spot for the Jacobites. Anthony Hope’s Prisoner of Zenda (1894) is set in Ruritania, a fictional kingdom with a Central European feel: highly cultured, Roman Catholic, and largely untouched by the Industrial Revolution. The two major themes are monarchical legitimacy and courtly love. The villain—Michael, Duke of Strelsau—is not only an usurper but a bounder. The heroes, the King of Ruritania and his American cousin Rudolph, are good Christian gentlemen. “I can thank God,” says Rudolph, “that I love the noblest lady in the world, the most gracious and beautiful, and that there was nothing in my love that made her fall short in her high duty.”

Meanwhile, Baroness Orczy’s The Scarlet Pimpernel (1905) is a variation on the theme by Edmund Burke. Here, too, we find noble aristocrats persecuted by jealous commoners. The opening lines could have been taken from the pages of L’Action Francaise:

A surging, seething, murmuring crowd of beings that are human only in name, for to the eye and ear they seem naught but savage creatures, animated by vile passions and by the lust of vengeance and of hate. . . During the greater part of the day the guillotine had been kept busy at its ghastly work: all that France had boasted of in the past centuries, of ancient names, and blue blood, had paid toll to her desire for liberty and for fraternity.

We then follow the eponymous Pimpernel as he slips through Paris like a thief in the night, whisking aristocrats away to their English sanctuary.

After the romantic phase comes the imperialist. As the United Kingdom becomes more and more invested in its colonies—particularly those in Asia and Africa—the public’s imagination is drawn eastward. British authors respond in kind, setting their stories in these distant kingdoms.

The poet laureate of empire, of course, is Rudyard Kipling. His novel Kim (1901) is the first adventure novel since Robinson Crusoe to be considered a great work of literature. Modern Library named it one of the 100 Best Novels. Those categories are nonsense, but there’s no denying that Kim is a world-class piece of writing. The eponymous Anglo-Irish merchant goes wandering across India with a Tibetan lama before getting caught up in the Great Game: the struggle between England and Russia for control of the subcontinent.

Kipling’s knowledge of Indian geography, culture, and politics make Kim one of the most colorful adventure novels. Unlike poor Xury and Friday, the indigenous characters are not stereotypes. The novel’s only flaw is that it assumes the reader will know a fair bit about prewar Anglo-Russian relations. It hasn’t aged well, as the kids say. And that’s a shame. An earlier short story, “The Man Who Would Be King” (1888), has fared better in that respect, though it isn’t nearly as sumptuous as Kim.

Yet surely the greatest of these is H. Rider Haggard. Rider Haggard was that rarest of authors: a real-life adventurer who also happened to be a top-shelf stylist. Really, it’s amazing that Hemingway could have embraced his persona, knowing that Allan Quartermain—the narrator-hero of Rider Haggard’s masterpiece, King Solomon’s Mines (1885)—was at large in the literary world. “I’m a timid man,” Quartermain confesses on page one, “and don’t like violence, and am pretty sick of adventure. I wonder why I am going to write this book: it is not in my line.”

This is the beauty of Quartermain. For twenty-five years he’s worked as an elephant hunter in Africa, the life expectancy for men in his profession being about five. He doesn’t like his work, but he’s good at it, and he has a young son back in England he needs to support. Over and over again, he charges into battle for the sake of men who are little more than strangers. And yet, for all that, he thinks of himself as a coward.

In the novel, Quartermain and three companions cross a vast desert on foot to reach a range of mountains which are said to contain King Solomon’s legendary mines. Once they pass the range, they find a great civilization nestled in the valley below. There they must fight an evil king, Twala, and his vizir. This vizir happens to be a hag, a witch, with the terrible name of Gagool. Quartermain calls her a “wizened monkey-like figure” who creeps on all fours. And her face! Gagool is so withered by age that “in size it seemed no larger than the face of a year-old child.” She has “no nose to speak of; indeed, the visage might have been taken for that of a sun-dried corpse had it not been for a pair of large black eyes, still full of fire and intelligence, which gleamed and played under the snow-white eyebrows.”

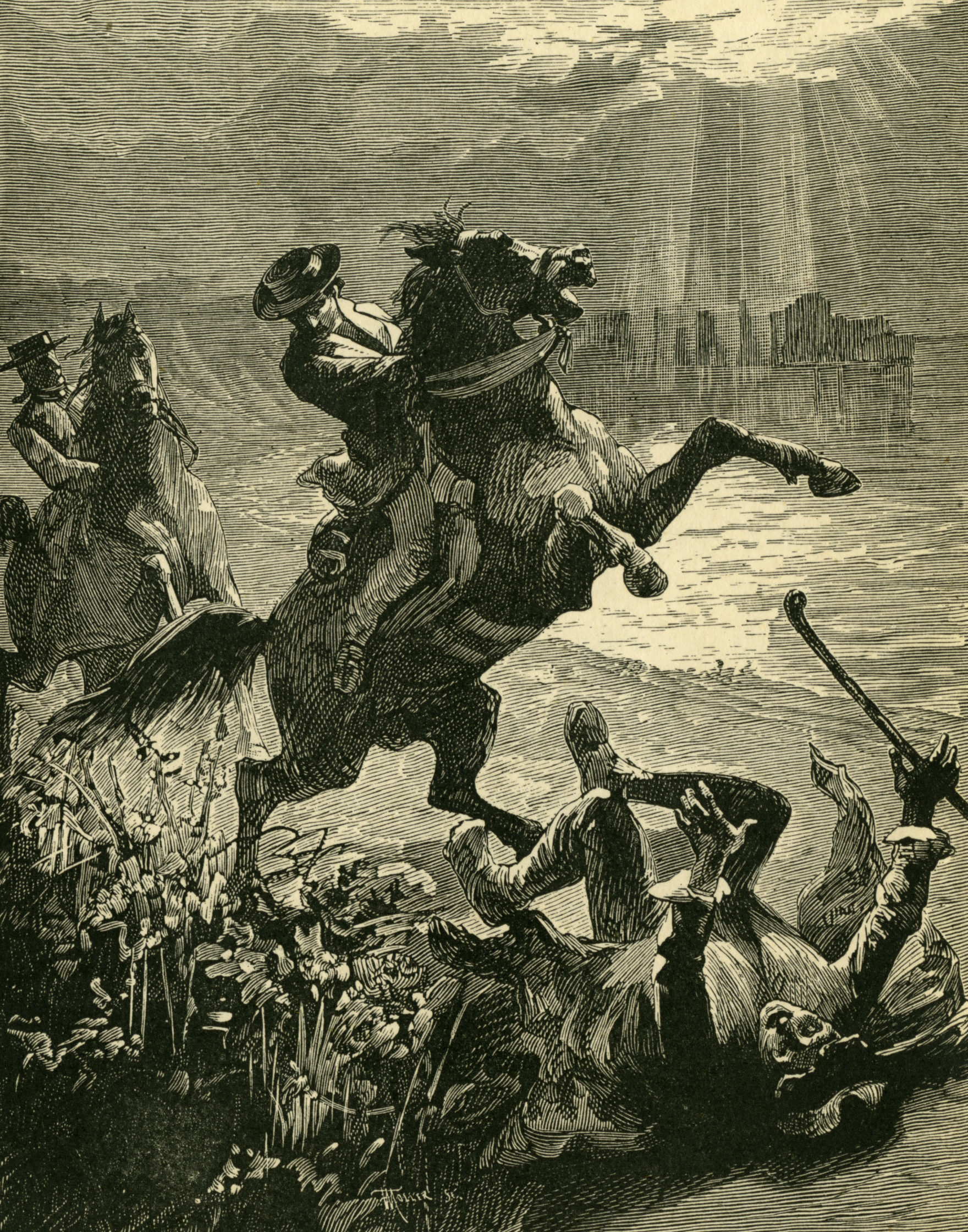

Quartermain and his friends discover that Twala is an usurper. Therefore, they must help the rightful king to raise up an army and retake his throne. As they prepare for the final battle, Quartermain looks out over his troops:

My mind’s eye singled out those who were sealed to slaughter, and there rushed in upon my heart a great sense of the mystery of human life, and an overwhelming sorrow at its futility and sadness. To-night these thousands slept their healthy sleep, to-morrow they, and many others with them, ourselves perhaps among them, would be stiffening in the cold; their wives would be widows, their children fatherless, and their place know them no more for ever. . .

Truly the universe is full of ghosts, not sheeted churchyard spectres, but the inextinguishable elements of individual life, which having once been, can never die, though they blend and change, and change again for ever.

Quartermain is not a stoic. That’s why we admire him, despite all his protests. If he was indifferent to life, he wouldn’t need courage. He could kill with impunity. He could sacrifice himself without a second thought. Instead, he’s deeply moved by every death in the book, from the servant-boy who is gored by an elephant to the dreaded Gagool.

The only hero that can possibly rival Quartermain is Richard Hannay. His creator, John Buchan, is to spy fiction what Jules Verne is to sci-fi: he invented the genre almost single-handedly, and rather by accident.

Buchan once quipped that his characters “had the knack of just squeezing out of unpleasant places,” which is true. But it’s a knack that doesn’t always make for a good story. His most famous book, The Thirty-Nine Steps (1915), doesn’t quite work, exactly because it all comes just a little too easy for Hannay. If the Germans want to kill him, why don’t they wait in his apartment after stabbing Scudder? And why don’t they search the dovecote? And how did they make plans with the fake Alloa?

The second Hannay novel is probably the best of them all. Greenmantle (1916) is a brilliant yarn about German occultism and radical Islam. Set during World War I, Hannay sneaks through the German Empire and into Ottoman Turkey in search of a prophet who seeks to rally the whole Muslim world in a great jihad against the Allies.

Reading it today, one can’t help but compare Hannay favorably to James Bond. For one, he’s pleasantly self-effacing, especially when it comes to the fairer sex. (“Women had never come much my way, and I knew as much of their ways as I knew about the Chinese language.”) He also takes great pains to see the best in everyone. He admires the strength and courage of Stumm, the sadistic German officer who chases him throughout the novel. He happens to meet the Kaiser at a train station and comes away feeling only pity for the tired old man. “I would not have been in his shoes for the throne of the Universe,” he reflects.

Hannay, too, regrets the death of each of his foes. This is a constant theme throughout Buchan’s work: the high premium he places on his characters, even his villains. “To be able to laugh and to show mercy,” Hannay declares, “are the only two things that make man better than the beasts.”

Like Robinson Crusoe, Phileas Fogg, David Balfour, Kim, and Allan Quartermain—and unlike virtually every character in modern literature—Richard Hannay has a great love for life. “I fancy it isn’t the men who get most out of the world and are always buoyant and cheerful that most fear to die,” he reflects. “Rather it is the weak-engined souls who go about with dull eyes, that cling most fiercely to life. They have not the joy of being alive which is a kind of earnest of immortality.” Personally I like Hannay’s take more than Quartermain’s.

The greatest adventure novel of them all is James Hilton’s Lost Horizon (1933). Objectively speaking, it’s the greatest novel ever written in English. There isn’t a single flaw in the whole book. The pacing is immaculate. The willing suspension of disbelief is achieved perfectly. The descriptions are gorgeous without ever being gratuitous. There’s just the right blend of English charm and Oriental mystique. The suspenseful mood mounts slowly, silently, for the reader as much as the characters. We share their fear, their suspicion, their claustrophobia.

Who can forget his first glimpse of Shangri-La?

Subscribe Today

Get daily emails in your inbox

A group of colored pavilions clung to the mountainside with none of the grim deliberation of a Rhineland castle, but rather with the chance delicacy of flower petals impaled upon a crag. It was superb and exquisite. An austere emotion carried the eye upward from milk-blue roofs to the gray rock bastion above, tremendous as the Wetterhorn above Grindelwald. Beyond that, in a dazzling pyramid, soared the snow slopes of Karakal. It might well be, Conway thought, the most terrifying mountainscape in the world, and he imagined the immense stress of snow and glacier against which the rock functioned as a gigantic retaining wall. Someday, perhaps, the whole mountain would split, and a half of Karakal’s icy splendor come toppling into the valley.

And who can be sure that, if he found himself in Conway’s shoes, he would have the courage to forsake the Valley of the Blue Moon?

“I confess I have a weakness for a novel that tells a story,” Hilton once wrote. “I believe that people like stories, and I believe that romantic and adventurous stories will hold their popularity because, with all its drawbacks, the romantic and adventurous view of life is the most sensible.” Poor Hemingway had a sense of adventure, but not of romance. His colleagues had neither. So Hiltonism remains the last literary taboo. Writers who embrace his philosophy are sure to have their novels dismissed as “boy’s books.” Yet his heresy is an old one. It goes back at least as far as Robinson Crusoe. And the tenets of Hiltonism are quite simple: be good and have fun. May we see their like again.