Fighting Pancho Villa’s Ghost

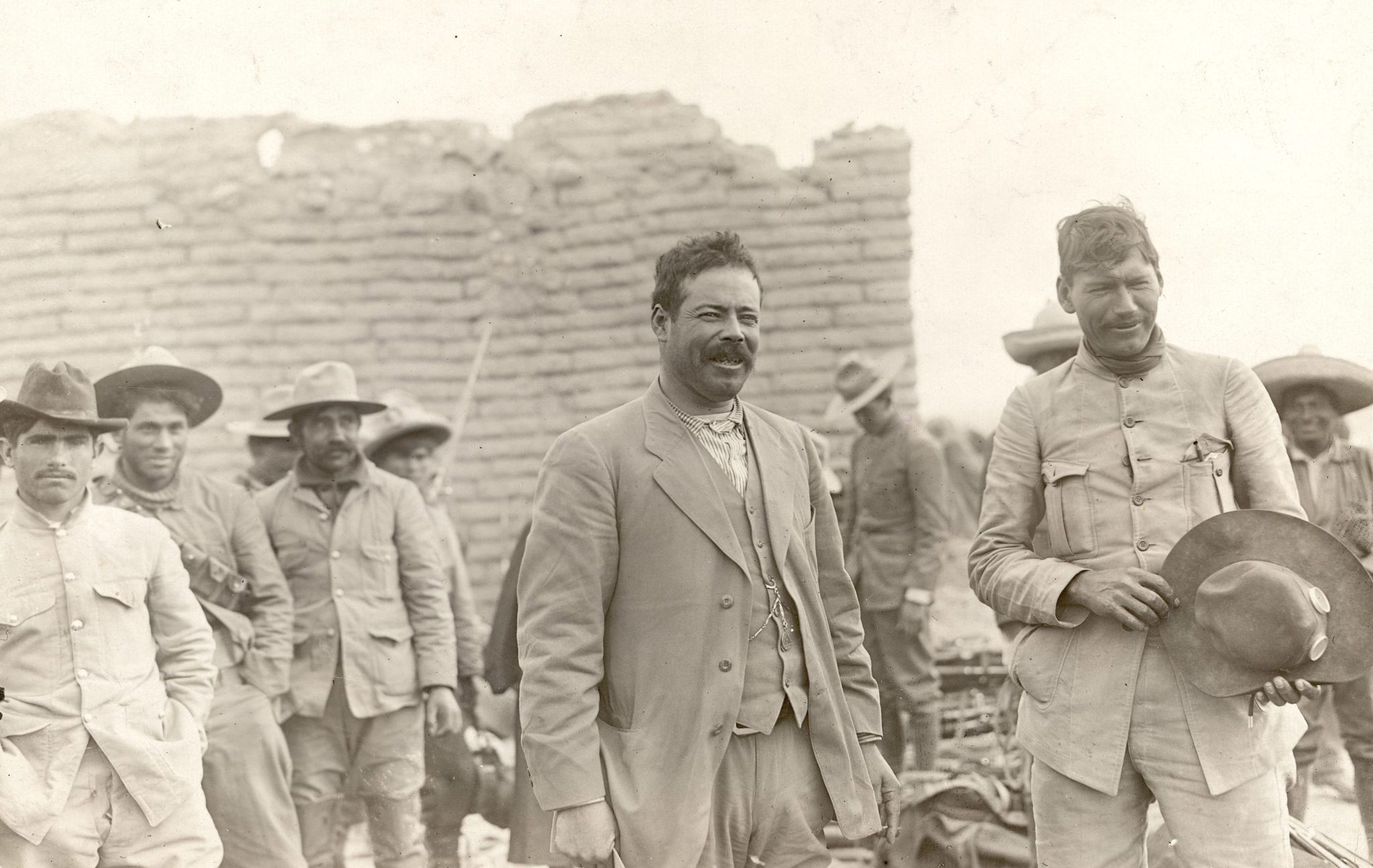

There are all kinds of Mexican food in the United States. Arizona features Sonoran-style cooking. New Mexico debates red and green chilies. Cal-Mex mastered Baja’s seafood. My favorite, Tex-Mex, contributes chili con carne and more than one helping of beef and cheese. Wherever it may be, and whatever variation of Mexico’s cuisine is on the menu, patrons will encounter a portrait of Pancho Villa on the restaurant’s wall.

Born José Doroteo Arango Arámbula, Pancho Villa’s rise from destitute peasant to Mexican folk legend and icon is a winding tale. After murdering a man accused of assaulting his sister, he fled to the Sierra Madre mountains, where he quickly rose to prominence as a bandit warlord. Arámbula changed his name to Pancho Villa and promptly earned a fierce reputation. Raiding and pillaging the lawless regions of northern Mexico during the waning years of the Porfirio Díaz regime, Villa would prove a thorn in the side of Mexico’s central government. He terrorized the haciendas of Mexico’s landowning elite and dashed Federales dispatched to capture him.

Villa generated the adoration of northern Mexico’s peasantry by fashioning himself against the Díaz regime. Keen to be seen as a “man of the people” and champion of the underclass, Villa embraced a “Robin Hood” persona. Legend holds Villa would strut the streets of Chihuahua, risking capture, handing peasants stolen wads of pesos and bricks of gold. Northern Mexico’s poor returned the favor by misinforming rurales of his whereabouts and providing his gang supplies.

Still, Villa was an unrepentant barbarian. He was known to execute captives, loot mercilessly, and burn. In one particularly gruesome account, he ordered his men to cut the feet off of a wealthy landowner who refused to hand over property. In another, Villa forced a man to dig his own grave before shooting him. While Villa commanded the sympathies of northern Mexico’s peasantry, most remained ambivalent or furiously hostile to the warlord.

Mexico’s 1910 election would change Villa’s trajectory. The Díaz regime, by then in power for three decades, faced a popular democratic groundswell in the form of Fransico Madero’s Partido Constitucional Progresista. The Díaz regime remained in power via fraudulent elections conducted to appease international (American) sentiment. Still, Francisco Madero’s movement for democratic reform inspired mass popular support. Despite the groundswell, Dìaz cruised to a comfortable victory with 98.93 percent of the popular vote.

Madero, an early proponent of election integrity, protested the results fiercely. He incited widespread rebellion against Díaz and declared himself the Provisional President of Mexico while taking refuge in San Antonio, Texas. Though the Díaz regime had previously wielded tacit American support, President William Taft mobilized American forces along the Mexican border, declaring his intention not to interfere unless American property and lives were threatened. This green-lighted Mexico’s radicals and set off the decade-long Mexican Revolution.

Madero’s revolt provided Pancho Villa’s first opportunity to escape his life of common thievery. Madero, seeking to cobble together a viable army, wrote Villa asking for the aid of his guerillas. Villa promptly pledged his support to Madero’s revolutionary cause and enlisted his Bandidos in the war. He also reconfigured his patronage of Mexico’s poor for revolutionary purposes, advocating for radical reform of Mexico’s de facto casta system and retribution for Mexico’s landowning elite. Akin to Jean Lafitte at New Orleans, Villa was repurposed from pirate to patriot.

Villa quickly developed into a worthy battlefield tactician, engineering rapid victories that forced the Díaz regime’s ignominious collapse and subsequent exile to Paris in 1911.

Francisco Madero was democratically elected thereafter but held a fractious grip on power. From late 1911 to 1913, Madero was simultaneously hampered by an institutionally conservative Díaz government and by radical reformers seeking a restructuring of Mexico’s landed class system. Madero’s tenuous government shortly collapsed during the “Decena Tragica” or “Ten Tragic Days.”

Mexican General Felix Diaz, a nephew of the former dictator, rallied forces and commenced a coup d’etat in February 1913. General Victoriano Huerta would defect from the Madero government days later, sealing Madero’s fate. Madero was deposed, and his vice president served a 45-minute term as president of Mexico before both men’s executions.

American Ambassador Henry Layne Wilson encouraged the coup, going as far as striking a deal between General Díaz and defecting General Victoriano Huerta to decide the post-coup leadership of Mexico. Wilson harbored sympathy for Mexico’s conservative elements, which were friendly to American business investment. He also maintained a personal distaste for President Madero. Wilson engineered Mexico’s coup during President Taft’s lame-duck period and the early stages of Woodrow Wilson’s administration without the approval or knowledge of either president. Known as “El Pacto de la Embajada” or “The Embassy Pact,” Ambassador Wilson’s diplomatic vigilantism would transform Mexico.

President Madero’s execution and General Huerta’s violent seizure of power in Mexico outraged the American public. When newly inaugurated President Woodrow Wilson was informed of Ambassador Wilson’s involvement in the Embassy Pact, he dispatched informants who reported the ambassador had acted in “treason” and was implicated in “assassination in an assault on constitutional government.” President Wilson dismissed Ambassador Wilson from his post within a month and refused to recognize the Huerta government.

Huerta’s usurpation (he’s known commonly in Mexico as “El Usurpador“) unleashed civil war. Pancho Villa, a proven tactician from the 1911 ouster of the Díaz regime, quickly gathered a force to resist the Hueristas and avenge Madero.

Villa formed the División Del Norte while serving briefly as the Provisional Governor of Chihuahua. He joined Emiliano Zapata’s Ejército Libertador del Sur and General Venustiano Carranza in opposition to Huerta. Under this assignment, Villa would forge his legacy as an able commander and revolutionary hero.

Villa won a decisive victory at Torreón, leading 16,000 troops in a day and night cavalry assault that revolutionized Mexican warfare. He landed his decisive blow at Zacatecas, defeating 12,000 Hueristas with a force of equal measure. After the battle, Villa confirmed his reputation for savagery. Estimates aren’t exact, but records agree that large numbers of civilians were indiscriminately executed, in addition to 500 Hueristas escorted to a local cemetery and executed by gunshots to the head.

Despite this carnage, Villa’s myth grew. Villa’s exploits attracted the attention of America’s chattering class. Newspaper editorials mythologized the Villistas, declaring them heroes for democracy. Hollywood filmmakers fanned across Northern Mexico, casting Villa and his men in staged battles. Villa, already a hero to Mexico’s poor, emerged as an international icon. Despite the Mexican War’s notable brutalism, the Washington Times editorialized that Villa’s campaign was a “campaign of modern and humane warfare.” A weapons-for-livestock scheme provided American aid to various rebel factions, including Villa’s, that soon swayed the war’s outcome.

General Huerta abandoned Mexico City for exile in Spain in July 1914, after his defeat at Zacatecas. As before, the Villista victory was short-lived.

Within months of Villa’s Constitutionalist victory, he was back at war. Villa and southern radical General Emiliano Zapata broke with General Carranza, who had seized the presidency of Mexico shortly after Huerta’s defeat. A civil war between victors swept across Mexico.

The Wilson administration, astonished at Mexico’s quagmire, suspended material support for Pancho Villa and disallowed further weapons shipments to rebel armies. The Carranza government was ostensibly democratic, and in fear of German agitation in Mexico, Wilson’s interest in nation-building was supplanted by a desire for stability. The U.S. joined a host of Latin American countries and recognized the Carranza government in October 1915, cutting off their one-time Villista partners.

Carranza’s armies, unlike Díaz’s or Huerta’s, served Villa’s División del Norte their first significant defeat at the Battle of Celaya in 1915. Villa lost 6,000 men to Carranza’s 695. Carranza’s forces had internalized the lessons of the Great War in Europe. They decimated Villa’s cavalry from entrenched positions with machine guns, barbed wire, and field guns. Villa’s outmoded army would suffer a string of defeats, permanently driving his beleaguered army back into Northern Mexico by 1916.

Villa had been reduced from a general of large armies to the leader of a guerrilla band. Under duress, Villa’s innate violence intensified. His men wantonly terrorized. He committed infamous atrocities, ordering the Rape of Namiquipa and personally executing a priest at San Pedro De La Cueva.

Villa’s anger with President Wilson’s perceived betrayal also boiled over. Cut off from arms shipments and indignant over the U.S. recognition of Carranza’s government, the División del Norte began to attack Americans in early 1916. The Herald Democrat, a local Texas paper, reported the first news of Villa’s wrath:

The mutilated bodies of 18 Americans killed Monday afternoon by Villa bandits near Santa Ysabel, Chihuahua, arrived in Juarez at 2:16 this morning.

Villa’s bandits sacked a train and murdered 18 U.S. miners. Once Villa’s ally and enabler, American media promptly turned on him. Though accounts of the Santa Ysabel Massacre are dubious, the Associated Press reported Villa’s order to “Kill all Yankees, loot, burn.” The American public was incensed. Newspapers across the country called for intervention. General John Pershing declared martial law to quell a race riot in El Paso.

After months of further violence, Villa struck Columbus, New Mexico. The Villistas, supplied with intelligence indicating only 30 U.S. troops were stationed in Columbus, attacked the town with 1,500 men. It was a mistake. The Villistas were actually attacking 341 U.S. troops from the 13th Cavalry Regiment who had recently relocated to the town. American troops fired thousands of rounds from an M1909 Benét–Mercié machine gun, cowing the bandits and repulsing them across the border.

President Wilson ordered General Pershing to pursue and capture Pancho Villa. Ten thousand U.S. Army personnel engaged in the pursuit across Mexico, known as the “Punitive Expedition.” The army used airplanes for surveillance for the first time in its history. A young Lieutenant George Patton mounted a machine gun on a truck while pursuing Bandidos on horseback. It was the first recorded use of mobile warfare, a glimpse into Patton’s future.

General Pershing’s pursuit lasted 11 months. Unable to gain refuge from air reconnaissance of the Sierra Madres, Villa’s men lost faith and wilted under sustained pressure from the U.S. Army. Again, the Villistas would be reduced from a brigade to a ragged mob. Villa would never again wield requisite power or hubris to threaten the United States directly.

The Punitive Expedition, however, was not without cost. Sixty five Americans perished in the pursuit of Villa, and Villa remained on the loose. The Expedition also inflamed tensions between the U.S. and Mexico. The United States had flagrantly tinkered with Mexican sovereignty in an incoherent, irresponsible manner throughout the Revolution. Mexicans had suffered irreparable catastrophe and humiliation that manifested in potent resentment. Local populations fed American troops false information throughout the hunt for Villa. They aided Villa’s men with supplies and shelter and pressured the Carranza government to resist further American violations. United outrage finally forced the Carranza Government to confront the Americans at Carrizal, forcing President Wilson to withdraw the Expedition rather than risk escalation. With a war in Europe on the horizon, Wilson could ill afford a war with Villa and the Carranza government.

Upon returning to the U.S., General Pershing naturally declared victory in public. Privately he harshly criticized Wilson’s diplomatic restraints and admitted defeat. Villa would continue to plunder Northern Mexico and resist the Carranza government but never attempted to campaign against the United States again.

Pancho Villa would fight his last major battle at the Battle of Ciudad Juárez in 1919. There he attempted to capture El Paso’s twin city with 9,500 men. Already matched by Carranza’s force, the Villistas were forced to flee when the U.S. Army crossed the border in pursuit. Just weeks later, Villa’s once-mighty army was once more reduced to a rabble.

The odyssey would end as violently as it began. Mexico’s revolution would end with yet another coup d’etat by yet another Huerta in 1920. Adolfo De La Huerta granted Villa full pardon and amnesty, allowing him to spend his final years at his Hacienda de la Limpia Concepción de Canutillo. After a few years of quiet, Villa announced his intention to re-enter political life ahead of the 1924 Federal Elections. On a drive to visit Parral, seven riflemen fired forty-plus rounds into Pancho Villa’s Dodge touring car, ending his ambitions. Once known as “La Cucaracha” for his seeming invincibility, Pancho Villa was buried in Parral before a procession of thousands.

For the Northeastern ruling elite, Pancho Villa’s life and myth passed into the shadows when the Hollywood films and editorials their predecessors commissioned faded to memory. He’s a novelty, sold as a t-shirt at dopey smoke shops, and the namesake of a Finnish restaurant chain. Epic Records produced the #1 Billboard hit “Pancho and Lefty” in 1982. So the story ends, we’re told.

But peasants still impoverished by hangovers of the casta system cross Villa’s battlefields on their way to the Rio Grande. Bandit warlords still patronize villages, buying loyalty and insulating their operations from the hated Federales. American troops are still sent into dangerous quagmires by Presidents with foolish half-commitments and incoherent diplomacy. Exercises in nation-building, disguised as “addressing root causes,” still undermine the Mexican people and blur American security commitments. The Sierra Madre Mountains remain untamed, bidding defiance to modernity as the West is wired and paved.

Indeed, Pancho Villa’s spirit still roams the deserts of the Southwest. And when you sit down in a restaurant with your family for enchiladas or drink a margarita with friends and see La Cucaracha’s photo, listen closely to the ranchera music on loop. You may yet hear the warning of El Corrido de la Persecución de Villa:

Cuando supieron que Villa ya era muerto,

todos gritaban henchidos de furor:

ahora sí, queridos compañeros,

vamos a Texas cubiertos con honor.

Mas no sabían que Villa estaba vivo

y que con él nunca iban a poder;

si querían hacerle una visita

hasta la sierra lo podían ir a ver.When they learned that Villa was already dead,

they all shouted in a frenzy:

“Now for sure, dear fellow soldiers,

we’ll go to Texas covered in honors.”

But they didn’t know Villa was alive

and that they would never be able to defeat him;

if they wanted to see him

they could go all the way to the mountains to do it.

Comments