Family Through the Plexiglass Window

Editor’s note: This is the ninth in a collaborative series with the R Street Institute exploring conservative approaches to criminal justice reform.

Society often defines individuals who commit crime as criminals, offenders, or convicts. Yet these labels ignore the reality of who these people are to the innocent parties left behind: mother, father, husband, wife, daughter, or son.

Policymakers have lost sight of the second-hand suffering that families endure as a result of a loved one’s crime and incarceration; they discount the centrality of the family to an individual’s rehabilitation—and to public safety as a whole. While those who commit crimes must be held accountable for their actions, society must also work to ensure that any second-hand harm to families is minimized and to provide a pathway for familial restoration.

Healthy families serve as incubators to supervise and nurture the development of children as productive and moral citizens. For this reason, children who are separated from their primary caretakers at a young age are more likely to struggle to form the healthy attachments that are so critical to development. And in some cases, parental incarceration may bring negative repercussions for a child’s health, stigmatization, antisocial behavior, economic insecurity, and household instability.

Government laws and policies cannot mold a child’s moral character and integrity. Nor can fiscal support remove the pain of a parent’s absence or a child’s shame. Our homes serve as the first learning environment, allowing children the space to cultivate the skills, support, and character necessary for successful lives. Due to their unquestionable role in raising children, avoiding nonessential separations of families should be of the utmost importance to policymakers. And when incarceration is the necessary form of punishment, policies should support continued family interactions and equip parents to be better communicators and more positive role models even while behind bars. Such policies also prepare them to be even better, more effective parents when they return home.

Far from simply promoting strong family units, pro-family policies may also offer additional returns to public safety. Research suggests that individuals who report stronger familial ties are less likely to be re-incarcerated. Indeed, in one study, individuals who received visitors while incarcerated were 13 percent less likely to be re-convicted and 25 percent less likely to have a technical violation revocation compared to those who did not. This demonstrates that close relationships with one’s child and family members can ease an individual’s transition back to the community and provide motivation for change. Thus, criminal justice reform must refine and supplement current policies to increase opportunities for family engagement during incarceration.

Yet our federal and state criminal justice systems have traditionally showcased little consideration of the impact the decision to incarcerate has on children, mothers, and fathers. Currently, about 2.7 million children have an incarcerated parent, leaving many of them without the emotionally, psychologically, or financially supportive relationship of a mother or father.

Per their design, prisons uproot individuals from their community, isolating them from their traditional support systems and their families from the individuals they love. During this time, visits and phone calls serve as a vital connection between the outside world and the incarcerated individual. Yet far too often, these options are inaccessible or unnecessarily expensive, which merely places additional burdens on families. As one example, in order to visit her husband, Mahealani Meheul was forced to travel 3,000 miles, costing her $1,000 to $1,200 for each visit. Further, in Arizona, families of incarcerated people have to pay to see their loved ones–a one-time fee of $25 per person.

Even telephone calls and video visits can incur exorbitant costs to families. A low-quality video service can cost as much as $12.99 for a 20 minute conversation. State prisons and local jails are themselves at fault for a substantial portion of this cost to families. In 2013, phone companies paid correctional facilities $460 million in concession fees in order to ensure exclusive contracts. And while a portion of these concession fees may be used to pay for security and monitoring costs during phone calls, a substantial portion is misused to subsidize other state costs. In an age with unprecedented and cheap technological communication ability, this steep pricing is not just outrageous—it’s a clear money-making scheme for states that is detrimental to reentry and families at home.

What’s more, there are alternatives to incarceration that some states are already exploring —like sentencing alternatives, diversion programs, or various kinds of treatment. And, when incarceration is necessary, several states are including families in the process of transformation.

Washington, for example, has enacted sentencing alternatives directly targeting parents who serve a critical role in their children’s lives. And, in 2015, Oregon enacted a Family Sentencing Alternative Pilot Program in five counties. A recent report notes that due to their participation, program participants were more patient with children and demonstrated “increased engagement and motivation to be successful while on supervision, and increased enthusiasm about the future.” Such alternatives work because they uniquely recognize the potential damage of parental incarceration to children and seek to minimize or avoid this harm. Furthermore, they promote the transformation of the individual into a better parent as well as a more productive citizen.

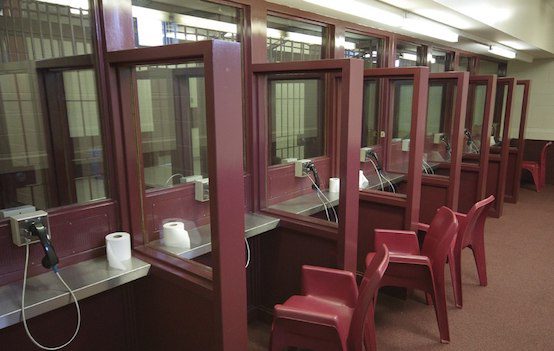

Pro-family reforms are slowly changing the settings of prisons and jails for the cases in which a period of incarceration is the best method of accountability. Some facilities are literally removing barriers to parent-child contact, by creating new, more child-friendly spaces for visits with incarcerated family members. Instead of talking behind a Plexiglass wall, parents can now hold and play with their children. These family interactions can promote parent-child attachment and reduce child anxiety during a parent’s time away. And in some situations, in-person visitation can be included within larger parenting programming, which gives incarcerated parents an opportunity to practice newly acquired skills, while their children have an opportunity to spend valuable time with mom or dad.

States can further mitigate the problem of distance by locating individuals in facilities closest to family, and by minimizing transfers to out-of-town facilities. When visits are not possible or affordable, free video visitation may span the distance (but video visitation should only supplement, not replace face-to-face). A recent report found that after implementing video visiting services, 74% of jails completely discontinued their in-person visits. This anti-family policy disrespects the importance of families by relegating them to talking through a screen. Rather than restricting a form of contact, video visitation should be encouraged as an additional method of communication.

If the family is the building block of society, then policy should demonstrate its importance. Criminal justice reform ultimately must be a pro-family movement, which recognizes that healthy families can be both the guard against future crime and the impetus for change while weak families are the beginning of society’s undoing.

Emily Mooney (@emilymmooney) and SteVon Felton are criminal justice policy associates at R Street Institute.