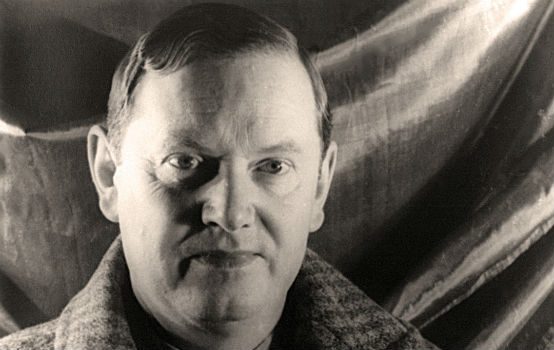

Evelyn Waugh in America

Evelyn Waugh’s first trip to America was a disaster (except that it inspired The Loved One). He hated nearly every aspect of American life. His second trip was different. Joshua Hren explains:

Whether motivated by masochism, a whim of magnanimity or money to be made on a Life magazine article on Catholicism in the States, Waugh returned to America in 1948. This time he met Dorothy Day, whom he described as ‘an autocratic ascetic saint who wants us all to be poor.’ He offered lunch to Day and her Catholic Worker fellow travelers in an Italian restaurant. Although she did not approve of the cocktails he bought and shared at considerable expense, the group stayed and talked for hours.

Waugh would later visit the Catholic Worker contributor and National Book Award-winning writer J. F. Powers in St. Paul, Minn. Powers did his part to dispel the rumors that cast Waugh as more of a cartoon than the character he already was: ‘Saw Waugh…all a lie about liveried servants. Carried out his dishes himself.’

During the same travels, while delivering a series of lectures on ‘Three Vital Writers: Chesterton, Knox, and Greene,’ Waugh stopped at Gethsemani Abbey in Kentucky to see Thomas Merton. Merton was indebted to Waugh, who provided extensive edits to the ‘long winded’ Seven Storey Mountain. The book came out in England one-third shorter and with Waugh’s recommended title, Elected Silences. The younger Merton repaid his debt, in part, through spiritual friendship, advising Waugh to ‘say the Rosary every day. If you don’t like it, so much the better.’ The monk hoped the beads would assist with Waugh’s anxiety over imperfect contrition. To Merton’s mind, Waugh was a man ‘with intellectual gifts’ arguing himself ‘into a quandary that doesn’t exist.’

In Waugh’s review of the book he helped rewrite, he was more charitable toward U.S. society: ‘Americans…are learning to draw away from what is distracting in their own civilization while remaining in their own borders.’ Elected Silences, with its ‘fresh, simple, colloquial’ ethos, came as a revelatory shock for ‘non-Catholic Americans,’ who were altogether unaware of ‘warmth silently generated in these furnaces of devotion.’ Waugh went further, anticipating that the United States would soon witness a flourishing monastic revival. Championing the Benedictine option long before the Benedict option became chic, Waugh proclaimed the modern world increasingly uninhabitable, calling us back to the age of Boniface, Gregory and Augustine: ‘As in the Dark Ages the cloister offers the sanest and most civilized way of life.’

What Waugh would make of America today is an open question, though he certainly would hate contemporary England. Read the rest of Hren’s piece.

One of the magazines I read regularly (in addition to this venerable publication—check out our latest issue) is The Spectator. First published in 1828, it is celebrating its 10,000th issue this month. Tom Holland tells the story of its founding and its particular tone: “The New Statesman, Prospect, Standpoint: all have a certain quality of moral earnestness that one could imagine Gladstone admiring. The Spectator, by contrast, seems to breathe the coffee-perfumed air of an earlier age. Right from its first edition, it has been shaded by the spectre of a vanished sensibility. In its morals, its values, its style, there is little of the wing-collar about it. Dress The Spectator up in period costume, and it would have to sport a powdered wig. The magazine has always cast a certain wistful gaze back at the 18th century. This is evident enough from its title. To launch a new publication back in 1828 was no less a leap of faith than it would be today — but to call it The Spectator was a gesture of self-confidence so lavish that it might have seemed to verge on the conceited. The original Spectator, founded in 1711, was a daily publication which, despite folding after a year, had come to be enshrined over the course of the 18th century as a supreme model of English prose.”

Of course, as much as I enjoy the articles, I read Spec primarily for its cultural coverage, and Richard Bratby provides a nice survey of the books and arts pages across the years: “The Spectator has spent 10,000 issues identifying the dominant cultural phenomena of the day and being difficult about them. ‘We cannot congratulate ourselves upon the progress of the musical art in London. The same routine of sinfonias by Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, and Spohr; the same overtures by Cherubini, Weber, and Romberg… are gone through, and the aggregate of taste remains pretty equal,’ begins the first ever arts column on 5 July 1828 . . . The ‘somewhat sordid’ Jane Eyre was frostily reviewed in 1847 (‘neither the heroine nor hero attracts sympathy’), and Verdi’s La Traviata received a pasting in 1856, principally for the heroine’s ‘infamous’ morality. The Spectator was quicker to appreciate the qualities of Turner’s ‘Fighting Temeraire’ in August 1844, though quicker still to denounce ‘those freaks of extravagance that detract from the beauty and obscure the meaning of too many of Turner’s works’. But Dickens is the main exhibit in the hall of shame, and the length and rigour of The Spectator’s famous slating of Bleak House in September 1853 can’t quite dispel an aroma of snobbery.”

And yet, while The Spectator certainly takes books and art seriously, it never takes itself too seriously—a refreshing relief from the overwrought moral earnestness and puritanical pronouncements that one finds in most literary publications today. While folks drone on about how literature should improve us, The Spectator reminds us that it should entertain first. As Frank O’Hara said (who, I am sure, was a Spectator reader, though I have absolutely no evidence for it): “Improves them for what? For death? Why hurry them along?”

In other news: Amanda Mull looks at the weird world of COVID19 advertising.

The last Renaissance man? “Paul Valery was one of the last of the writers in the Goethe mold — a man aspiring to universal knowledge, who hoped to bend science toward the vaguer ends of art while subjecting artistic practice to scientific discipline. He is thought of mainly as a poet, but verse was a small part of his output, which included essays on epistemology and architecture, meditations on Leonardo da Vinci, and 30,000 pages of notebooks that many scholars consider his masterpiece.”

Here’s a video of the theft of Van Gogh’s The Parsonage Garden at Nuenen in Spring in Holland a few weeks ago.

Speaking of videos, the first YouTube video was uploaded 15 years ago. Here it is.

Andrew L. Shea revisits Roger Fry’s short tenure as Curator of Paintings at the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “The story is recounted in an essay from Caroline Elam’s Roger Fry and Italian Art (Paul Holberton Publishing), which, as a scholarly volume, is an exceptional dive into the mind of an intellectual who deserves more attention than he usually gets nowadays, as well as the Italian masterworks with which he engaged over the course of his life. Fry, whom Kenneth Clark called ‘incomparably the greatest influence on taste since Ruskin,’ is best known for his studies in England. He was an active member of the Bloomsbury group (Virginia Woolf wrote his biography), one of the founders of The Burlington Magazine (the nation’s first scholarly journal of art history), and a prodigious lecturer on painting who did perhaps more than anyone to bring an understanding of the French avant-garde to the Anglophone world . . . Though Fry’s tenure at the Met is regarded by most as a failure on the whole, it did beget a number of crucial acquisitions.”

Troll of the year: Amazon gives £250,000 to British bookstores.

Photo: Sankt Goarshausen

Receive Prufrock in your inbox every weekday morning. Subscribe here.