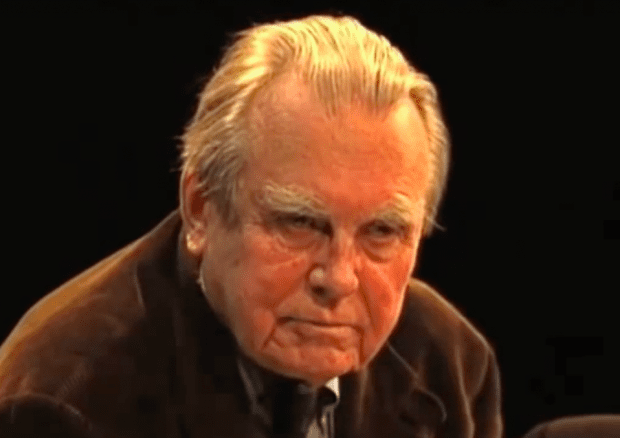

Why Did Czeslaw Milosz Believe?

I’ve been reading today To Begin Where I Am, selected essays of the Polish poet and thinker Czeslaw Milosz (1911-2004). Here is a passage from “If Only This Could Be Said,” in which Milosz attempts to articulate his religious beliefs. He was a liberal intellectual, and also a believing Catholic, though his faith involved real struggle between the rigid piety that was the ineradicable inheritance of his youth, and both his carnality and awareness of his own weakness.

Milosz writes:

Here, perhaps, is where I part ways with many people with whom I would like to be in solidarity but cannot be. To put it very simply and bluntly, I must ask if I believe that the four Gospels tell the truth. My answer to this is: “Yes.” So I believe in an absurdity, that Jesus rose from the dead? Just answer without any of those evasions and artful tricks employed by theologians: “Yes or no?” I answer: “Yes,” and by that response I nullify death’s omnipotence. If I am mistaken in my faith, I offer it as a challenge to the Spirit of the Earth. He is a powerful enemy; his field is the world as mathematical necessity, and in the face of earthly powers how weak an act of faith in the incarnate God seems to be.

More:

Hypocrisy and exaltation: struggling with my two souls, I cannot break free of them. One: passionate, fanatical, unyielding in its attachment to discipline and duty, to the enemy of the world; Manichaean, identifying sex with the work of the Devil. The other: reckless, pagan, sensual, ignoble, perfidious. And how could the ascetic in me, with the clenched jaws, think well of that other me?…

Here is a rich passage in which Milosz reflects on the dispossession of Catholics in the post-Vatican II world:

Nowadays, we tend to exaggerate the difficulty of having faith; in the past, when religion was a matter of custom, very few people would have been able to say what and how they believed. There existed an intermediary stratum of half-conscious convictions, as it were, supported by trust in the priestly caste. The division of social functions also occurred in the field of religion. “Ordinary” mortals turned to the priests, setting the terms of an unwritten contract: We will till the soil, go to war, engage in trade, and you will mutter prayers for us, sprinkle holy water, perform pious singing, and preserve in your tomes knowledge about what we must believe in. An important component of the aura that surrounded me in my childhood was the presence of clergy, who were distinguished from those around them by their clothing, and in daily life and in church by their gestures and language. The soutane, the chasuble, the priest’s ascending the steps before the altar, his intonations in Latin, in the name of and in lieu of the faithful, created a sense of security, the feeling that there is something in reserve, something to fall back on as a last resort; that they, the priestly caste, do this “for us.” Men have a strong need for authority, and I believe this need was unusually strong in me; when the clergy took off their priestly robes after Vatican II, I felt that something was lacking. Ritual and theater are ruled by similar laws: we know that the actor dressed up as a king is not a king, or so it would seem, but to a certain extent we believe that he is. The Latin, the shimmering chasubles, the priest’s position with his face toward the altar and his back to the faithful, made him an actor in a sacral theater. After Vatican II the clergy shed not only their robes and Latin but also, at least here, where I write this, the language of centuries-old formulas which they had used in their sermons. When, however, they began speaking in the language of newspapers, their lack of intellectual preparation was revealed, along with the weakness of timid, often unprepossessing people who showed deference to “the world,” which we, the laity, had already had enough of.

The child who dwells inside us trusts that there are wise men somewhere who know the truth. That is the source of the beauty and passion of intellectual pursuits — in philosophical and theological books, in lecture halls. Various “initiations into mystery” were also said to satisfy that need, be it through the alchemist’s workshop or acceptance into a lodge (let us recall Mozart’s Magic Flute). As we move from youthful enthusiasms to the bitterness of maturity, it becomes ever more difficult to anticipate that we will discover the center of true wisdom, and then one day, suddenly, we realize that others expect to hear dazzling truths from us (literal or figurative) graybeards.

Among Catholics that process was until recently eased by the consciousness that the clergy acted in a dual function: as actors of the sacred theater and as the “knowledgeable caste,” the bearers of dogmas dispensed, as if from a treasure house, by the center, the Vatican. By democratizing and anarchizing, up to and including the realm of what, it would seem, were the unassailable truths of faith, aggiornamento also struck a blow at the “knowing” function of the clergy. An entirely new and unusual situation arose in which, at least in those places where I was able to observe this, the flock at best tolerates its shepherds, who have very little idea of what to do. Because man is Homo ritualis, a search takes place for collectively created Form, but it is obvious that any liturgy (reaching deep into one or another interpretation of dogma) which is elaborated communally, experimentally, cannot help but take shape as a relative, interhuman Form.

Perhaps this is how it should be, and these are the incomprehensible paths of the Holy Spirit, the beginning of man’s maturity and of a universal priesthood instead of a priesthood of one caste? I do not want this to sound like an admission that the Protestant isolation of individuals is correct, on the basis of which each individual may treat religion as a completely personal matter; this is delusive and leads to unconscious social dependencies. It would be useless for man to try to touch fire with his bare hands; the same is true of the mysterious, sacral dimension of being, which man approaches only through metaxu, as Simone Weil calls it, through intermediaries such as fatherland, customs, language. It is true that although I would characterize my religion as childishly magical, formed on its deepest level by the metaxu which surrounded me in my childhood, it was the adhesions of Polishness in Catholicism that later distanced me from the Church. …

You may not know that Milosz went into a Western exile from communism in the 1950s. More:

Though circumstances disconnected me from the community of those praying in Polish, this does not mean that the “communal” side of Catholicism vanished for me. Quite the contrary; the coming together of a certain number of people to participate in something that exceeds them and unites them is, for me, one of the greatest of marvels, of significant experiences. Even though the majority of those who attend church are elderly (this was true two and three generations ago, too, which means that old age is a vocation, an order which everyone enters in turn), these old people, after all, were young however many years ago and not overly zealous in their practice at that time. It is precisely the frailty, the human infirmity, the ultimate human aloneness seeking to be rescued in the vestibule of the church, in other words, the subject of godless jokes about religion being for old ladies and grandfathers — it is precisely this that affords us transitory moments of heartbreaking empathy and establishes communion between “Eve’s exiles.” Sorrow and wonder intermingle in it, and often it is particularly joyous, as when, for example, fifteen thousand people gather in the underground basilica in Lourdes and together create a thrilling new mass ritual. Not inside the four walls of one’s room or in lecture halls or libraries, but through communal participation the veil is parted and for a brief moment the space of Imagination, with a capital I, is visible. Such moments allow us to recognize that our imagination is paltry, limited, and that the deliberations of theologians and philosophers are cut to its measure and therefore are completely inadequate for the religion of the Bible. Then complete, true imagination opens like a grand promise and the human privilege of recovery, just as William Blake prophesied.

Ought I to try to explain “why I believe”? I don’t think so. It should suffice if I attempt to convey the coloring or tone. If I believed that man can do good with his own powers, I would have no interest in Christianity. But he cannot, because he is enslaved to his own predatory, domineering instincts, which we may call proprium, or self-love, or the Specter. The proposition that even if some good is attainable by man, he does not deserve it, can be proved by experience. Domineering impulses cannot be rooted out, and they often accompany the feeling that one has been chosen to be a passive instrument of the good, that one is gifted with a mission; thus, a mixture of pride and humility, as in Mickiewicz, but also in so many other bards and prophets, which also makes it the motivator of action. This complete human poverty, since even what is most elevated must be supported and nourished by the aggression of the perverse “I” is, for me, an argument against any and all assumptions of a reliance on the natural order.

Evil grows and bears fruit, which is understandable, because it has logic and probability on its side and also, of course, strength. The resistance of tiny kernels of good, to which no one grants the power of causing far-reaching consequences, is entirely mysterious, however. Such seeming nothingness not only lasts but contains within itself enormous energy which is revealed gradually. One can draw momentous conclusions from this: despite their complete entanglement in earthly causality, human beings have a role in something that could be called superterrestrial causality, and thanks to it they are, potentially, miracle workers. The more harshly we judge human life as a hopeless undertaking and the more we rid ourselves of illusions, the closer we are to the truth, which is cruel. Yet it would be incomplete if we were to overlook the true “good news,” the news of victory. It may be difficult for young people to attain it. Only the passing of years demonstrates that our own good impulses and those of our contemporaries, if only short-lived, do not pass without a trace. This, in turn, inclines us to reflect on the hierarchical structure of being. If even creatures so convoluted and imperfect can accomplish something, how much more might creatures greater than they in the strength of their faith and love accomplish? And what about those who are even higher than they are? Divine humanity, the Incarnation, presents itself as the highest rung on this hierarchical ladder. To move mountains with a word is not for us, but this does not mean that it is impossible. Were not Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John miracle workers by virtue of their having written the Gospels?

What a marvelous writer! I’m going to be in Poland this summer; I hope to go pray at his grave in Krakow.