Early in the 1996 election campaign Dick Morris and Mark Penn, two of Bill Clinton’s advisers, discovered a polling technique that proved to be one of the best ways of determining whether a voter was more likely to choose Clinton or Bob Dole for President. Respondents were asked five questions, four of which tested attitudes toward sex: Do you believe homosexuality is morally wrong? Do you ever personally look at pornography? Would you look down on someone who had an affair while married? Do you believe sex before marriage is morally wrong? The fifth question was whether religion was very important in the voter’s life.

Respondents who took the “liberal” stand on three of the five questions supported Clinton over Dole by a two-to-one ratio; those who took a liberal stand on four or five questions were, not surprisingly, even more likely to support Clinton. The same was true in reverse for those who took a “conservative” stand on three or more of the questions. (Someone taking the liberal position, as pollsters define it, dismisses the idea that homosexuality is morally wrong, admits to looking at pornography, doesn’t look down on a married person having an affair, regards sex before marriage as morally acceptable, and views religion as not a very important part of daily life.) According to Morris and Penn, these questions were better vote predictors—and better indicators of partisan inclination—than anything else except party affiliation or the race of the voter (black voters are overwhelmingly Democratic).

Tomorrow’s Social Conservatism Today

Thomas Fazi is a socialist journalist based in Europe, and the author of an interesting Twitter thread (starting here) on the changing definition of what it means to be a social conservative. Here’s a threaded, easy-to-read version. Excerpts:

The fall of Labour’s “red wall” and the crushing Tory victory in the recent UK elections has ignited a heated debate about the causes of Labour’s defeat. Apart from the most obvious causes (Brexit, media bias etc.), there is one alleged cause that is causing much controversy:

Labour’s inability to connect to a growing number of working class voters that are left-leaning on economic issues but – unlike the Labour establishment – “conservative” on social/cultural issues. Hence the latter’s drift towards the Tories.

The most vocal proponents of this idea are those associated with @blue_labour, which have been arguing for a long time for “a socialism which is economically radical and culturally conservative”.

In classic example of left-Pavlovian response, Malik seems unwilling to confront these uncomfortable truths, preferring to take comfort in the fact that a minority of the working class is pro-immigration – enough to dismiss notions of working class conservatism as “nonsense”.

Malik’s argument gets even more contradictory from here on: to the extent, he says, that immigration is perceived as a problem – a fact he denied until a moment earlier – it is only because immigration has become “symbolic” of the working class’ loss of identity, community etc.In other words, Malik says, immigration is not the cause but rather the symptom of working class anxieties over not only its growing material precariousness but also over its loss of collective identity and social atomisation.It’s not clear what caused this “erosion of the more intangible aspects of [workers’] lives” for Malik – probably a vague notion of “neoliberalism”. But his solution is clear: the left must not base its attempts to rebuild community on “notions of national or ethnic identity”.

Rather, they should be based on “struggles to transform society, from battles for decent working conditions to campaigns for equal rights”, which “created organisations […] which drew individuals into new modes of collective life”.

This, however, represents a clear denial of reality [Malik’s dismissal of nationalism — RD]. As important as narrower (local, political, religious, etc.) forms of identity may be, many studies show that national identity is not only very real, but it remains the strongest form of collective identity around the world.

Even among the young (less than 25 years old), those with a university education and professionals, national identity trumps local and – even more massively – regional (such as European) or global attachments, except among the globe-trotting cosmopolitan elites.A country’s national identity (like nations themselves) may be, to a large extent, an “imaginary” construct. It may also be hard to pin down, encompassing customs, culture, history language, institutions, religion, social mores, etc. But it exists and has very “real” effects…

… creating common bonds among members of – and giving rise to – a territorially defined community (demos). To deny the existence of the latter is, in effect, to deny the existence of society itself. All that’s left is a bunch of individuals that happen to share a piece of land.

The woke left likes to vilify the nation-state, but all the major social, economic and political advancements of the past centuries were achieved through the institutions of the democratic nation-state, not through international, multilateral or supranational institutions.

Furthermore, modern concepts of nat. identity are incredibly “progressive”, based as they are on transcending individual particularities – sex, race, biology, religion, etc. – to create cultural-political identities based on participation, equality, citizenship, representation.

For woke leftists to raise the spectre of “whiteness” whenever the topic of national identity is mentioned is simply a testament to their ignorance. Modern national identities have nothing to do with biology and are indeed extraordinarily inclusive and “open”.

Thus, when we speak of working class or societal values, we are not talking of a specific set of predefined values. We are simply talking of whatever values, norms etc. happen to characterise a specific national community at any point in time.

This is not an argument against the evolution of national identity. It is an argument for respecting a national community’s right to have a say in the pace and form that such evolution takes. To ignore the latter is, quite simply, political suicide.We are now in a position to offer a different explanation of “social conservatism”: this is simply society’s self-defence against those factors – internal or external – that are perceived as threatening its members’ need for community, belonging, rootedness and identity.

Labour’s continued survival as a working class party, I would argue, depends on its ability to engage with this need.

I hope you’ll read the whole thing. It’s not long, and it will give you more context to understand the passages I’ve quoted here. Fazi sounds like an interesting person to follow on Twitter, which you can do here: @battleforeurope.

You are, of course, wondering about how this changing definition of social conservatism applies to American politics. Unlike Britain, Christianity is still a political force in the US, though a diminishing one. The main political issues separating social conservatism from social liberalism have been abortion and homosexuality. The research organization PRRI used those two issues as its measure in 2018 of the relative social (cultural) conservatism of each state:

In 2003, Thomas B. Edsall, one of the best political journalists we have, wrote a really interesting piece for The Atlantic on how the “morality gap” has become the “key variable” in American politics. Excerpt:

It is an axiom of American politics that people vote their pocketbooks, and for seventy years the key political divisions in the United States were indeed economic. The Democratic and Republican Parties were aligned, as a general rule, with different economic interests. Electoral fortunes rose and fell with economic cycles. But over the past several elections a new political configuration has begun to emerge—one that has transformed the composition of the parties and is beginning to alter their relative chances for ballot-box success. What is the force behind this transformation? In a word, sex.

Whereas elections once pitted the party of the working class against the party of Wall Street, they now pit voters who believe in a fixed and universal morality against those who see moral issues, especially sexual ones, as elastic and subject to personal choice.

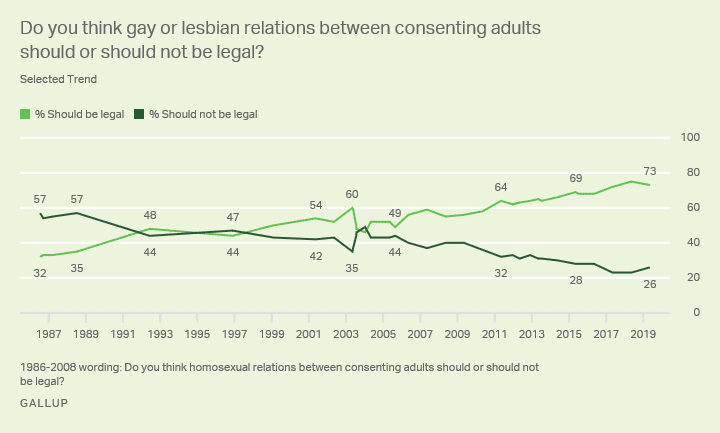

That was nearly a quarter-century ago. Times have changed. Boy, have they! In that period, Americans have become far more liberal about sexual matters. Fundamental support for abortion rights has not changed much since 1973. With the coming of the Internet and the advent of smartphones in 2007, pornography is ubiquitous, and considered now to be a normal part of life. And gay marriage is widely popular. Look at this Gallup trendline below. In 1996, the country was split down the middle not over gay marriage (27 percent supported it then; today, 63 percent do), but over whether gay sex should be legal!

Plus, the bottom is falling out of Christianity, especially among the younger generations. Pew has details on that, but this Gallup graphic tells the same story:

Some Christians will want to argue with this, and say that holding a “church membership” is not the same thing as being a religious believer. Strictly speaking, that’s true, but it’s mostly irrelevant when trying to understand broad cultural trends, and what they have to tell us about politics.

The bottom line is that for various reasons, the Culture War as it has been defined since 1980 — as something primarily about sex — has been settled in favor of the cultural Left. There are still many, many more conventional social conservatives in the US than in Britain: that is, people who are religiously observant, and who hold traditional views on abortion, marriage, homosexuality, and sexual morality in general. I am one of these people. But we are not ascendant, and it’s hard to see how we could become ascendant in the short term.

Britain is showing to us that the meaning of “social conservatism” has changed there, and is rapidly changing in the same way here. It’s easier to see in Britain, where religion is relatively unimportant. Both establishment liberals and establishment conservatives have their own reasons for wanting to hold on to outdated definitions of social conservatism. If it had not been for the Evangelical leaders who went so gung-ho for Trump in 2016, giving journalists and others reasons to jump up and down about the supposed hypocrisy of those churchmen, we probably would have been able to perceive more clearly the shift of “social conservatism” away from sexual issues, and over to Thomas Fazi’s definition: “society’s self-defence against those factors – internal or external – that are perceived as threatening its members’ need for community, belonging, rootedness and identity.”

If you’ve been reading me since the mid-2000s, you know that I’ve been arguing since around 2006 that the longterm trends for social and religious conservatives on gay marriage were not good, and that we would be much better off basing our activism on the importance of defending religious liberty. In light of Fazi’s tweetstorm, that stance of mine looks to me like a rudimentary way of saying that conservative politics ought to shift towards helping communities and community institutions protect themselves against fast-moving social changes that threaten its need for community, belonging, rootedness and identity.

It’s very hard in America to argue against individual rights. There’s no longterm future in arguing against gay rights in general. That is simply the hard reality of this time and place. And it seems clear that defending ourselves by posing religious liberty as more important than gay rights when the two clash is also a non-starter in a secularizing country. So, I wonder: if the emerging social conservatism in the US, as in the UK, is going to be about the rate of change, and local control over factors that threaten social cohesion and identity, then maybe religious conservatives ought to articulate our arguments not in terms of rights clashes, but instead as part of a general opposition to forces tearing apart community, rootedness, and identity.

I’m not quite sure how this would work, or if it would work. But we need to be thinking in these terms. Remember, sex didn’t become the “key variable” in American politics until the Sexual Revolution of the 1960s and 1970s, and its aftermath, re-sorted the political parties. Prior to 1968, there was broad agreement in America on sexual matters. As Edsall pointed out, our politics back then were fought primarily over New Deal economic issues, though the Civil Rights movement pushed race into the center too. Sex, though, was not a big political issue, because there was broad consensus on the political issues emerging from sexual morality.

Until there wasn’t. Now, though, with the possible exception of transgenderism, Americans appear to be well on their way to reaching a new consensus on sexual matters. That Donald Trump became the GOP’s nominee in 2016, and then the president, shows how outdated the old consensus is. I think it’s fair to call out conservative Christian leaders who gave their full-throated endorsement to Trump, but this Facebook statement from conservative Princeton professor Robert George is a good partial explanation of what the political form of religious conservatism looks like in the new era:

Whatever one thinks of Donald Trump (and my own views about the President’s delinquencies are well known) surely it’s not hard to understand why large numbers of Evangelicals and Catholics favor him over any of the Democrats seeking their party’s nomination (despite the fact that many Evangelicals and Catholics aren’t happy about the President’s character, coarse rhetoric, and some of his polices). There is the fealty of every single one of the Democratic nominees–every single one–to the abortion and sex lib lobbies. If you believe, as Evangelicals and Catholics believe, that abortion is the unjust killing of innocent and defenseless members of the human family, then it is nigh impossible to imagine circumstances under which one could support a politician who pledges to work night and day to deny unborn children any legal protection against the lethal violence now visited with impunity upon nearly a million of them each year. And that is precisely the pledge every Democratic candidate makes to Planned Parenthood, NARAL, and the entire base of their party. But that’s only for starters.

Evangelicals and Catholics have watched as Democrats and progressives across the country have worked to shut down Catholic and other religious foster care and adoption agencies because, as a matter of conscience, these agencies place children in homes with a mom and a dad. They have watched as cake bakers, florists, caterers, wedding planners, and others (even the pizza shop-owning O’Connor family ad the software designer Brendan Eich) have been harrassed in efforts to drive them out of business and deprive them of their livelihoods because of their beliefs about marriage and sexual morality. They have watched as the Democratic and progressive mayor of Atlanta terminated the employment of Kelvin Cochran, the city’s Fire Chief, for the same reason–he had published a book upholding Biblical teaching on marriage and sexual morality. They have watched as Democrats and progressives have tried to “cleanse” entire fields of medicine and healthcare of Evangelicals, Catholics, and other pro-life people by imposing on them requirements to implicate themselves in the taking of innocent life by abortion. They watched as Beto O’Rourke proposed–over no truly meaningful opposition from his fellow Democratic presidential aspirants–to selectively yank the tax exempt status from churches and other religious organizations that refused to fall in line with progressive ideological orthodoxy on sex and marriage.

I could go on.

Now, none of this is to deny that there are some Evangelicals and Catholics (and other Trump supporters) who seem entirely to overlook Donald Trump’s faults and failings. They see nothing but good in the man. But at least in my experience these Evangelicals and Catholics are in the minority. Most recognize his faults and failings and wish he were better. Their support for him is based on a prudential judgment that the overall situation for the common good would be made much worse if he were to lose to one of the Democrats. And they fear–with justification–that the consequences for themselves and their religious institutions would be dire if such a thing were to happen. In this respect, their position is formally like that of their anti-Trump co-religionists who favor a Democrat because their prudential judgment is that, though a Democratic president would do great harm to values they cherish (such as the sanctity of human life, and religious liberty and the rights of conscience), the harm would be less than the harm Trump will do to those values and others in the long run.

My point here is not to try to adjudicate this dispute. (For what it’s worth, I think that it’s a more complicated business than most people on either side suppose. I may say more about that on another occasion after I’ve reflected on it a good deal more.) It is simply to say that no one should be surprised that many Evangelicals and Catholics (including some like my pal Keith Pavlischek who refused to vote for Trump in 2016) support the President over the Democratic alternatives. Whether one assesses and weights the reasons as they do or not, they do have reasons.

I say a partial explanation, because Prof. George is still arguing on the moral substance of abortion and sexual morality. And there’s nothing wrong with that! I completely agree with him. But note the defensiveness in his articulation of the rationale for voting for Trump Republicans. I don’t say “defensiveness” as a word of criticism. As the socialist Thomas Fazi says, people whose traditions, institutions, and identities are under siege are right to defend themselves. The point I want to make, though, is that we should understand that we are engaging in legitimate self-defense here, and we should explore the possibilities of reframing our own interests as tied to the economic and non-religious cultural interests of working-class people who vote left.

To restate: Tomorrow’s social conservatism will not be about sex. It will be about nationalism and identity. I fear that if this is not managed carefully, it will end up being, in the US, about race. The Left has already staked out its position that social liberalism, on this front, is about being anti-white. I hope that the Right can and will define social conservatism not as pro-white, but pro-American, in the sense of fighting for fair and just treatment for all Americans, regardless of race. I think that still has purchase among Americans. I hope so.

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.