Sunday Morning At Auschwitz

On Sunday morning, I went to Auschwitz. I had to take an Uber there from the Tyniec monastery. It was jarring to take Uber to Auschwitz. It was jarring to pass by strip malls and movie theaters and all the usual signs of modern life only a short walking distance from the scene of world-historical mass murder. Watching through the car window older Poles walking to mass down the streets of Oswiecim, I wondered what it’s like to live in a town that is forever associated with infamy — even though your people were victims, not perpetrators.

I have the sense that I’m like someone who ran to the melting-down Chernobyl reactor to see what was happening, and now have to wait to see the effects of radiation poisoning. It wouldn’t be correct to say that “nothing prepares you for Auschwitz.” In fact, our culture does a pretty good job preparing people for Auschwitz, though I will agree that standing in front of the infamous “Arbeit Macht Frei” gate really does give you a jolt. The entire time I walked around the grounds, I was praying my prayer rope for the souls of the dead. If I’m honest, I was also praying it, in a sense, for myself — as a kind of shield against the moral horror of what I was seeing.

Because there’s nothing to say about Auschwitz that hasn’t been said a million times already, I’ll keep this short, and restricted to my own brief impressions.

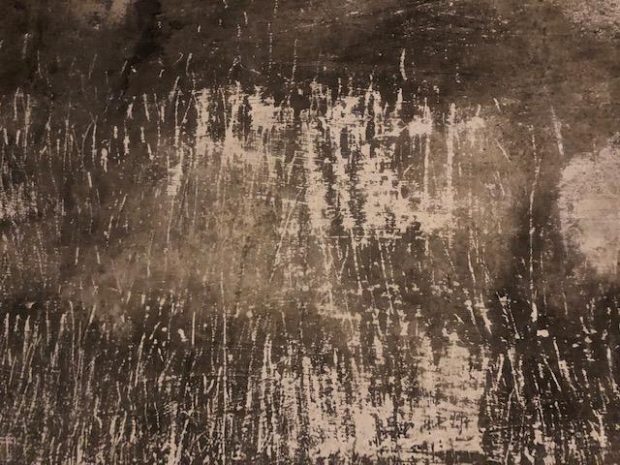

I didn’t realize that there are actually two Auschwitzs — Auschwitz II, which is 2 km away from the first camp, is called Birkenau. They are very different places, though also the same. The first Auschwitz is where the most interesting things are, because it was where the Germans tried their worst things; Birkenau is what they built when the number of Jews and others being brought to Auschwitz I overwhelmed its capacity to murder them. There’s not as much to see at Birkenau, because by the time the Nazis built it, they had it all down to a science. The vastness of Birkenau is what knocks you flat. I took the photo above just inside the red brick gate (the “Arbeit Macht Frei” gate is at Auschwitz I):

Imagine train cars lined up about as far as you can see, disgorging human beings. That’s what happened here. The great contemporary historian of Poland, Norman Davies, writes:

It took only twenty minutes between the arrival of a train load to be undressed and “disinfected” [gassed] and the arrival of the special detachments to strip the corpses of hair, gold fillings, and personal jewellery at the entrance to the crematorium. Hair mattresses, bone fertilizer, and soap from human fat were delivered to German industry with Prussian precision.

The barracks and crematoria covered a massive plain. I could not count them all. Most of them have been allowed to rot; all that remains are crumbling chimneys from the small stoves inside the barracks, meant to keep the inmates warm. This gives the site the appearance of a dead forest. When historians say that the Germans were doing industrial-scale murder, this is what they mean. I really could not have conceived of this without seeing the size of Birkenau. It is a platitude (if speaking of Auschwitz can ever be that) to call Auschwitz-Birkenau a killing machine, but confronting it with your own eyes — especially Birkenau — reveals the truth of that observation with staggering clarity. It could not have been more efficient.

That was Birkenau — which I saw after I had toured Auschwitz I.

Two things jumped out at me about Auschwitz I. First, how utterly banal it is. Again, that platitude, that cliche: the banality of evil. But seriously: it’s true here, like nowhere else I’ve ever seen. If you didn’t know what had happened there, it would look like a dull barracks. You’ll walk by a building, and stop to read the museum marker, and it will say something like, “In this building, Dr. Josef Mengele…”. There’s a room there where the museum displays hair the Nazis harvested from female corpses, and sold to textile makers. There was over one ton of it. Do you know how much human hair it takes to make a ton? Enough to fill a small house! I also saw a cell where prisoners sentenced to death by deliberate starvation were kept. Father Maximilian Kolbe, a Catholic saint, died in that cell.

The second thing that jumped out at me was how mind-blowingly bureaucratic it all was. Again, this is something historians tell us, but you really need to examine the documents on display there to grasp the perversity of this. The Germans kept records of everything. It was so methodical. If somehow this site had been the place of a battlefield massacre, it would have been more comprehensible. But this was about as premeditated as it gets. It makes you ashamed to be human.

The whole thing made me aware of our capacity, as human beings, to do this kind of thing, and to hide what we do behind forms and papers and ideas. There was handwritten testimony there by Rudolf Hoess, the Auschwitz commandant from 1940-43 (later hanged there as a war criminal), who wrote about receiving the order from Himmler to start gassing Jews. Himmler told him this in a face to face meeting in 1941. Hoess wrote (this is from the Yad Vashem website):

We discussed the ways and means of effecting the extermination. This could only be done by gassing, since it would have been absolutely impossible to dispose by shooting of the large numbers of people that were expected, and it would have placed too heavy a burden on the SS men who had to carry it out, especially because of the women and children among the victims.

Can you believe that? They came up with mass gassing in part to spare the tender feelings of SS men, who would feel bad about shooting women and children. Again, this is not news, but to see it at Auschwitz, in Hoess’s own handwriting — there’s nothing like it.

Human nature never changes

Here’s what the inside of a gas chamber looks like:

I wondered if those scratch marks were from the hands of the dead, but a guide told me no. In the room next to the gas chamber were these ovens for burning bodies:

In the car riding out to Auschwitz, I had caught up on my Twitter feed, and read initial reports about the BBC’s new documentary in which former Labour Party employees spoke out about anti-Semitism in the party, and Jeremy Corbyn’s upper management team trying to squelch complaints. Here’s the latest, from The Guardian on that story. Excerpt:

Several other officials told the programme that dealing with the scale of the complaints took a severe toll on their mental health. Kat Buckingham, the former chief investigator in the disputes team, said she had a breakdown and had decided to leave the party.

“I couldn’t hold the tide and I felt so powerless and I felt guilty and I felt like I failed,” she told the programme.

This was on my mind when I saw those ovens. Labour Party leadership is institutionalizing anti-Semitism, according to whistleblowers within the party, commenting on the controversy that has dogged Labour ever since the far-left leader Jeremy Corbyn took over the party’s leadership three years ago.

Look at this. These are clothes taken off children that were later gassed:

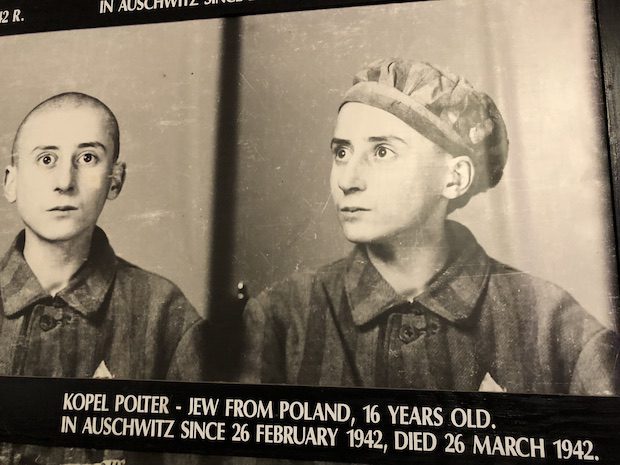

This young man’s photo hangs on the wall with those of other children and teenagers. Look at his eyes. I have a son about the same age as Kopel Polter:

And of course these empty cans:

I remember thinking as I was walking out of Birkenau that the only thing harder than believing in God after Auschwitz is not believing in Him. There is an outdoor exhibition outside the gates of Auschwitz I featured photos and excerpts of contemporary interviews with Auschwitz survivors, reflecting on their religious thoughts after Auschwitz. Here’s a story from the Times of Israel about the exhibition.

As I walked through it, the rain began, and it came down hard, but I couldn’t tear myself away from reading the words of these survivors. Punctuation below is in the original inscriptions at the exhibit.

Here’s something from Tzipora Fayga Waller, a Hungarian Jew:

I was 18 years old. During the selection in Auschwitz, I held onto my aunt’s child. Mengele motioned me to the left. I did not understand. He screamed at me “is that child yours?” I said “no.” He took Avrumy from me and pushed me to the right. I didn’t know what it meant then. We believed Hashem [the Most High — a name of God] was going to help us. But it didn’t work. I was the first born, and the only one that survived. What I learned from my experience in Auschwitz is to believe in kindness. Be good to the people around you.

Here’s one from Avraham Zelcer, a Czech Jew:

I was 16 years old. The train stopped in Auschwitz on the morning of Shavuos. We thanked God we arrived. The horrors of our transport from Czechoslovakia were beyond words. So many people suffered and died. We didn’t know what was waiting for us. Women and children to the left. I went to the right. I asked someone: “where are the women and children?” He pointed to a tall chimney: “they went out through there.” The only way out of Auschwitz was through the chimney: today, tomorrow, or the next day. It took me a year after liberation to return to my faith.

From Ernest Rumi Gelb, also from Czechoslovakia:

I was 17 years old. I remember our daily marches to work every day in Auschwitz. Invariably there was someone who knew the morning davening [prayer] by heart. I am not sure I felt like praying, but I did. The impulse for rejection was strong. Prayer, however, was a reminder of God. On Rosh Hashanah, as on all days, we were forbidden to pray. But we did it on the marches. Commiserating with other Jews through prayer was important for me. We could all hope and imagine together that, God willing, next year we would be out of there.

From Rabbi Nissan Mangel (Czech-born):

I was 11 years old. The fires of Auschwitz made some people lose their faith. one morning, I was marching with others in the camp. A man in the group saw a yingele [Jewish boy], dead, hanging from the gallows. He screamed, “where are you God!” Another man responded, “you know where God is? He is on the gallows with the boy. That’s where he is.” I saw the exact same barbarity. The man could not reconcile what he saw with a compassionate God. My father taught me that fire makes things hard, or it can make them melt. My emunah [faith] became stronger that day.

One more, from Irving Roth, also Czech:

I was 14 years old. it was the day before Yom Kippur. I was hungry, frightened. I couldn’t eat my piece of bread. I could not drink the coffee. Looking back, as a religious man, I ask myself today how did I live through this? I decided that my quarrel was not with God, but with man. It was man that created the gas chamber. Not God. In spite of all that the Nazis took from me, I made choices in the midst of this meaningless terror. I made decisions about how I would conduct myself. Fatih was the only thing left. I took comfort in it.

As I was leaving Birkenau, I thought: ifI had survived imprisonment at Auschwitz and thought God didn’t exist, and that ultimate justice would be impossible, I don’t know how I would be able to go on living.

My next thought was a Christian one: about how deeply right it is that God would take the form of a man persecuted and put to death by torture, and would overcome that death through resurrection. After Auschwitz, the logic of the Incarnation and the Passion made sense to me at a deep level, in a way that it had not before.

I also thought about how forgiveness is the only way to maintain civilization. There is no way Germany could ever atone for the Holocaust. No way. In fact, I have to say I admire the moral courage of the German visitors I saw at Auschwitz that morning (I knew they were German because I heard a guide speaking to them in German.) I would not be able to bear the shame of it.

Leszek Kolakowski, whose essay collection Is God Happy? has been my constant companion in Poland, writes about theodicy (the branch of theology concerned with reconciling an all-powerful, all-just, and all-merciful deity with the existence of evil):

People today do not lose their faith because of the evil they see around them. Unbelievers perceive evil in a way that is already determined by their unbelief: the two are mutually supporting. The same holds true of the faithful: they perceive evil in light of their faith, which is consequently affirmed rather than weakened by what they see. So there seem to be no good grounds for saying that the evil of our time casts doubts on the presence of God; there is no compelling logical or psychological connection.

Similarly with science: Pascal was terrified by the “eternal silence” of infinite Cartesian space; but both this silence and the voice of God are in the ear of the listener. God’s presence or absence lies in belief or unbelief, and each of these attitudes, once adopted, will be confirmed by everything we see around us.

The meaning of the godless Enlightenment has not yet become apparent, because the breakdown of the old faith and the collapse of the Enlightenment are taking place simultaneously, both before our eyes and in our hearts.

In the same essay, he wrote:

The collapse of Christianity so eagerly awaited and so joyfully greeted by the Enlightenment turned out — to the extent that it really occurred — to be almost simultaneous with the collapse of the Enlightenment. The new, radiant anthropocentric order that was to arise and supplant God once He had been deposed never appeared.

I have long believed that the Holocaust was the most important event of the 20th century, and maybe the most important event in human history outside the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ, because it tells us the truth about who we are. That no matter how advanced we become, in culture, education, and technology, we are capable of doing this to each other. It wasn’t just the Germans. The Soviets did something like this too. As did the Red Chinese. What happened in Auschwitz could happen anywhere, given the right set of circumstances.

I can understand how someone would lose their faith in God because of the Holocaust. What I can’t understand is how they could retain their faith in Man. There is no such thing as a radiant anthropocentric order. It’s a lie, and only fools believe it. They are fellow travelers of Christian fools who believe in a happy-clappy God of Your Best Life now.

And that’s all I have to say about it, for now.