Suicide Of The Humanities

This NYT profile of Dan-el Padilla Peralta, a radical Princeton Classics scholar, epitomizes what is wrong with the academic humanities in this radical era, and how dangerous the radicalization is to all of us.

Dan-el Padilla Peralta is a black Dominican Classics scholar at Princeton. He is also the leading figure in a move to tear down the field of Classics, which is the study of Ancient Greece and Rome. He came to this country as a small child when his mother required medical treatment in New York for complications related to the impending birth of his younger brother. After the brother was born, the family decided to stay in the US illegally. Eventually the father went back to the Dominican Republic; the mother and the children remained in the US, trying to regularize their immigration status.

As a nine-year-old boy living in a Chinatown homeless shelter, Padilla started reading about history. A child’s textbook about the Classical world lit a fire in his mind. An older New Yorker saw the child reading a big book about Napoleon Bonaparte, and decided to help him get a good education. Padilla went to an excellent school in New York, on scholarship, and excelled. Then:

Years passed before Padilla started to question the way the textbook had presented the classical world to him. He was accepted on a full scholarship to Princeton, where he was often the only Black person in his Latin and Greek courses. “The hardest thing for me as I was making my way into the discipline as a college student was appreciating how lonely I might be,” Padilla told me. In his sophomore year, when it came time to select a major, the most forceful resistance to his choice came from his close friends, many of whom were also immigrants or the children of immigrants. They asked Padilla questions he felt unprepared to answer. What are you doing with this blanquito stuff? How is this going to help us? Padilla argued that he and others shouldn’t shun certain pursuits just because the world said they weren’t for Black and brown people. There was a special joy and vindication in upending their expectations, but he found he wasn’t completely satisfied by his own arguments. The question of classics’ utility was not a trivial one. How could he take his education in Latin and Greek and make it into something liberatory? “That became the most urgent question that guided me through my undergraduate years and beyond,” Padilla said.

OK, this is interesting. In order to justify his devotion to Classics in the eyes of these intellectual bullies, who challenged his own loyalty to the tribe, he decided to instrumentalize his scholarship.

I want you to imagine that an Evangelical Christian undergraduate at Princeton being approached by other Evangelical Christian students, and asked to explain why he is studying all this Pagan stuff. How is this going to lead people to Christ? And imagine that he deals with that inner shame and guilt by deciding to instrumentalize his scholarship, to turn the Classics into a field that is not studied for its own sake, but for how it can be used to advance something extraneous to itself.

What would you think of a person like that, and his personal Christian crusade, becoming one of the most influential scholars in that academic field? What if, in part because of his work, and a religious Awakening among American academia, Classics became a field that had to be understood through an Evangelical Christian lens — and that those who disagreed stood accused of defending Paganism, and being infidels?

You would recognize it as a corruption of the field. Well, that’s what’s happening here, in terms of ideology, with Dan-el Padilla Peralta as a prophet of the Great Awokening!

The story goes on to talk about how Padilla became interested in Roman slavery. Certainly a worthy topic! But over time:

Padilla began to feel that he had lost something in devoting himself to the classical tradition. As James Baldwin observed 35 years before, there was a price to the ticket. His earlier work on the Roman senatorial classes, which earned him a reputation as one of the best Roman historians of his generation, no longer moved him in the same way. Padilla sensed that his pursuit of classics had displaced other parts of his identity, just as classics and “Western civilization” had displaced other cultures and forms of knowledge. Recovering them would be essential to dismantling the white-supremacist framework in which both he and classics had become trapped. “I had to actively engage in the decolonization of my mind,” he told me. He revisited books by Frantz Fanon, Orlando Patterson and others working in the traditions of Afro-pessimism and psychoanalysis, Caribbean and Black studies. He also gravitated toward contemporary scholars like José Esteban Muñoz, Lorgia García Peña and Saidiya Hartman, who speak of race not as a physical fact but as a ghostly system of power relations that produces certain gestures, moods, emotions and states of being. They helped him think in more sophisticated terms about the workings of power in the ancient world, and in his own life.

The emphasis on the boldfaced line above was my own. Notice how the story’s author, Rachel Poser, assumes the truth of the rather radical claim that Classics is white supremacist. This kind of thing is why I read journalism about cultural matters these days with a skeptical eye. Again, let’s imagine that Padilla was an Evangelical Christian, and was conducting his crusade against the Classics as a religious act, within an academic world that was becoming much more Evangelical. Now, imagine that Rachel Poser, a contributing writer to The New York Times, was also an Evangelical Christian. Would she have written the line, “Recovering them would be essential to dismantling the anti-Christian framework in which both he and classics had become trapped”? Would editors at The New York Times have published that line? Journalism today just accepts these highly contestable claims about race as if they were revealed truths.

If Padilla sought to use aspects of his own racial identity to illuminate new approaches to Classics, this could be promising. But one would need to be careful to guard against one’s own subjectivity corrupting the work. Many times I have written in this space about the lecture I heard Dame Gillian Beard give at Cambridge in 2009, in which she explained how various factions in Victorian society appropriated Darwin’s findings as scientific justification for their favored causes. British imperialists asserted that Darwin showed why imperialism is scientifically sound, as the strong must rightly dominate the weak. Abolitionists, on the other hand, claimed that Darwin’s science showed why slavery should be abolished, as all men are the same, deep down. And so forth. What Padilla is doing, and what is catching on in the Classics field, is the capture of it by ideological antagonists.

The Times piece shows how influential Padilla has been, including at his own university:

That initiative, and the draw of Padilla as a mentor, has contributed to making Princeton’s graduate cohort one of the most diverse in the country. Pria Jackson, a Black predoctoral fellow who is the daughter of a mortician from New Mexico, told me that before she came to Princeton, she doubted that she could square her interest in classics with her commitment to social justice. “I didn’t think that I could do classics and make a difference in the world the way that I wanted to,” she said. “My perception of what it could do has changed.”

So he is teaching others to instrumentalize their scholarship, to make it serve ideological ends. This is intellectually corrupt. In the Soviet period, scholarship had to be made to fit the Marxist metanarrative. One former Soviet citizen I interviewed told me that history was taught as an anticipation of Marx’s revelation — that the Marxist interpretive framework was applied to everything, as if to make all of history before and after Marx center on Marx’s work. I am reading a good book now, Destiny Denied: A History of the World Through Islamic Eyes, by Tamim Ansary. In it, the author talks about how the Islamic world really was advanced in scholarship, until a crisis in 12th century was resolved on the side of religion. That is, leaders in the Muslim world decided that all knowledge should be subordinated to Koranic studies, and must be seen as a branch of religion. That was the intellectual death of the Muslim world, in Ansary’s telling.

This Great Awokening will be the intellectual death of the Western world too, if we let it. Some people in the Classics field understand that the efforts by Padilla and others to dismantle Classics is suicidal:

Privately, even some sympathetic classicists worry that Padilla’s approach will only hasten the field’s decline. “I’ve spoken to undergrad majors who say that they feel ashamed to tell their friends they’re studying classics,” Denis Feeney, Padilla’s colleague at Princeton, told me. “I think it’s sad.” He noted that the classical tradition has often been put to radical and disruptive uses. Civil rights movements and marginalized groups across the world have drawn inspiration from ancient texts in their fights for equality, from African-Americans to Irish Republicans to Haitian revolutionaries, who viewed their leader, Toussaint L’Ouverture, as a Black Spartacus. The heroines of Greek tragedy — untamed, righteous, destructive women like Euripides’ Medea — became symbols of patriarchal resistance for feminists like Simone de Beauvoir, and the descriptions of same-sex love in the poetry of Sappho and in the Platonic dialogues gave hope and solace to gay writers like Oscar Wilde.

“I very much admire Dan-el’s work, and like him, I deplore the lack of diversity in the classical profession,” Mary Beard told me via email. But “to ‘condemn’ classical culture would be as simplistic as to offer it unconditional admiration.” She went on: “My line has always been that the duty of the academic is to make things seem more complicated.” In a 2019 talk, Beard argued that “although classics may become politicized, it doesn’t actually have a politics,” meaning that, like the Bible, the classical tradition is a language of authority — a vocabulary that can be used for good or ill by would-be emancipators and oppressors alike. Over the centuries, classical civilization has acted as a model for people of many backgrounds, who turned it into a matrix through which they formed and debated ideas about beauty, ethics, power, nature, selfhood, citizenship and, of course, race. Anthony Grafton, the great Renaissance scholar, put it this way in his preface to “The Classical Tradition”: “An exhaustive exposition of the ways in which the world has defined itself with regard to Greco-Roman antiquity would be nothing less than a comprehensive history of the world.”

A few years ago, I gave a talk about how discovering Dante led me out of a deep personal crisis, and gave me new eyes with which to see myself and the world. In the Q&A period, a young woman who looked to be the age of a graduate student stood and asked me how I could actually believe that a white European male living in a time of oppression of women and minorities could have anything to say to us today. I thought she was kidding at first, and I’m afraid my answer was not the best it could have been. After the session ended, a professor in the audience approached me to say that that young woman’s point of view is standard in academia today. That really hit me hard, knowing well how the study of the past, and of the art and wisdom of figures very different from me set me free from some of the mind-forg’d manacles of my own making. This is the same thing as pompous white people saying that we have nothing to learn from non-white cultures, or Westerners thinking that non-Western thought and practice is without value. The woke have just turned these prejudices around, and see their bigotry as liberation.

What they are doing, though, is closing the door to future generations. More from the Times piece:

To see classics the way Padilla sees it means breaking the mirror; it means condemning the classical legacy as one of the most harmful stories we’ve told ourselves. Padilla is wary of colleagues who cite the radical uses of classics as a way to forestall change; he believes that such examples have been outmatched by the field’s long alliance with the forces of dominance and oppression. Classics and whiteness are the bones and sinew of the same body; they grew strong together, and they may have to die together. Classics deserves to survive only if it can become “a site of contestation” for the communities who have been denigrated by it in the past. This past semester, he co-taught a course, with the Activist Graduate School, called “Rupturing Tradition,” which pairs ancient texts with critical race theory and strategies for organizing. “I think that the politics of the living are what constitute classics as a site for productive inquiry,” he told me. “When folks think of classics, I would want them to think about folks of color.” But if classics fails his test, Padilla and others are ready to give it up. “I would get rid of classics altogether,” Walter Scheidel, another of Padilla’s former advisers at Stanford, told me. “I don’t think it should exist as an academic field.”

If this doesn’t terrify you, you’re not seeing it for what it is. These scholars believe that the Classics field should exist only for the sake of its own destruction! It is completely perverse. My kids attend a school where everybody studies Latin, and there’s a lot of reading in the Greeks and the Romans. If any of my children fell in love with the Classics and wanted to study them, I would have to discourage them from going into the field, which is committing suicide.

More:

Amy Richlin, a feminist scholar at the University of California, Los Angeles, who helped lead the turn toward the study of women in the Roman world, laughed when I mentioned the idea of breaking up classics departments in the Ivy League. “Good luck getting rid of them,” she said. “These departments have endowments, and they’re not going to voluntarily dissolve themselves.” But when I pressed her on whether it was desirable, if not achievable, she became contemplative. Some in the discipline, particularly graduate students and untenured faculty members, worry that administrators at small colleges and public universities will simply use the changes as an excuse to cut programs. “One of the dubious successes of my generation is that it did break the canon,” Richlin told me. “I don’t think we could believe at the time that we would be putting ourselves out of business, but we did.” She added: “If they blew up the classics departments, that would really be the end.”

Exactly! You leftist scholars have worked so hard to denigrate your own fields of study as oppressive and wicked, so you shouldn’t be surprised when the bean-counters in university administration decide that they no longer want to support programs that perpetuate evil. Honestly, though, what is the point of a university supporting a department whose scholars think is worthless except for the opportunity it gives them to sit around talking about how worthless it is?

Here is how radicalism has damaged Padilla. He sees the door that opened to him through that book in the Chinatown shelter as a bad thing:

Padilla has said that he “cringes” when he remembers his youthful desire to be transformed by the classical tradition. Today he describes his discovery of the textbook at the Chinatown shelter as a sinister encounter, as though the book had been lying in wait for him. He compares the experience to a scene in one of Frederick Douglass’s autobiographies, when Mr. Auld, Douglass’s owner in Baltimore, chastises his wife for helping Douglass learn to read: “ ‘Now,’ said he, ‘if you teach that nigger (speaking of myself) how to read, there would be no keeping him. It would forever unfit him to be a slave.’” In that moment, Douglass says he understood that literacy was what separated white men from Black — “a new and special revelation, explaining dark and mysterious things.” “I would at times feel that learning to read had been a curse rather than a blessing,” Douglass writes. “It had given me a view of my wretched condition, without the remedy.” Learning the secret only deepened his sense of exclusion.

Padilla, like Douglass, now sees the moment of absorption into the classical, literary tradition as simultaneous with his apprehension of racial difference; he can no longer find pride or comfort in having used it to bring himself out of poverty. He permits himself no such relief. “Claiming dignity within this system of structural oppression,” Padilla has said, “requires full buy-in into its logic of valuation.” He refuses to “praise the architects of that trauma as having done right by you at the end.”

This man, Padilla, is poisoning the minds of the next generation. He is teaching those who should be carriers of the tradition to despise it. That Princeton employs an open saboteur in its Classics department is a sign of its death wish.

Finally, the story mentions last summer’s campus uproar when Padilla and sympathetic leftist scholars at Princeton (300 of them) came out with a reform proposal to fight “anti-Blackness” on campus — including one to establish a committee that would “oversee the investigation and discipline of racist behaviors, incidents, research and publication.” In other words, it would be a body that would seek to police academic discourse to punish those who offended against the True Religion. From the Times piece:

Punishing people for doing research that other people think is racist just does not seem like the right response.” But Padilla believes that the uproar over free speech is misguided. “I don’t see things like free speech or the exchange of ideas as ends in themselves,” he told me. “I have to be honest about that. I see them as a means to the end of human flourishing.”

There we are again: the instrumentalization of scholarship and academic pursuits. In Padilla’s world, you can only speak and think in ways that conform to his narrow idea of “human flourishing.” This is not just the death of Classics, but the death of the university.

There has to be some action now to save the humanities. Clearly the rot has spread very deeply into the institutions. There is not likely to be any reconquista of humanities faculties in the near term. What we need is a Benedict Option for the humanities — for the creation of academic monasteries within whose walls the tradition can survive this new Dark Age. Roger Scruton, Charles Taylor, Jacques Derrida and other scholars helped establish an underground degree-granting university in communist Czechoslovakia, so true scholarship could continue to live under the Marxist yoke, whose universities had been enslaved by ideology.

What would that look like here? What if alumni who cared about the humanities withdrew their donations from Princeton and all other woke citadels, and used them to build up a new, defiantly traditional college? Or, to massively strengthen and expand the few colleges and universities that still stand? And start new academic magazines to publish their work, and so forth?

It’s time. It really is. There are so many graduates of classical Christian schools now who are eager to learn in the old-fashioned way. Where can they go?

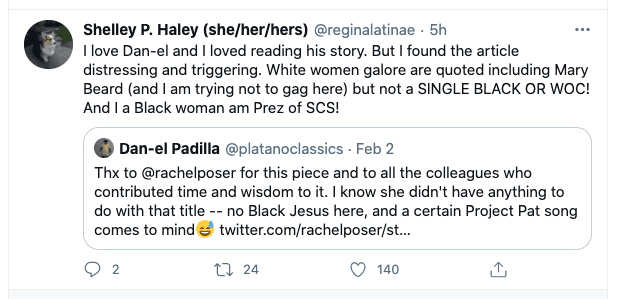

UPDATE: You can never, ever make the Woke happy. “Distressing” and “triggering”:

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.