Sabina, Our Hero

That image is from a short visual editorial about privacy in The New York Times, by Farhad Manjoo. The Times has just launched an editorial initiative called the Privacy Project, in which the editorial page will examine issues of privacy in the digital age. Today, editorial page editor James Bennet introduces the series by asking, “Do you know what you’ve given up?” He’s talking about how, for the sake of convenience, we have surrendered an immense amount of personal data, and access to data, to private corporations.

In his short visual editorial, Manjoo points out that in China, the government is the ultimate caretaker of this information on its citizens. Here in the US, the information is in the hands of private industry. My sense is that we don’t get all that upset about it because in our imagination, tyranny is something that the State imposes. The idea that corporations could not act as tyrants is a radical failure of imagination. In my next book, which is going to be about resisting this new soft totalitarianism, I’m going to be addressing this issue.

Writing in The New Atlantis, Jon Askonas explores how tech companies are ushering in a new tyranny. Askonas, a Catholic University of America professor, argues that the algorithms employed by companies like Google and Facebook do not only serve individual human desire, but craft it. (A more detailed version of this point is available in the new must-read book by Shoshana Zuboff, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism).

True story: just yesterday I was on the phone with a friend, talking about this stuff, and he told me about a friend of his who works for a tech marketing company that helps business clients use captured data to increase sales. Turns out that a super-high-end luxury car dealership hired the marketers, who set up a geofence around the dealership. Thus anybody who came near the dealership with a smartphone in hand had their smartphones automatically mined for information the dealership could use to sell luxury cars to the individual — this, without the individual being aware of what was being done. The data mining even revealed where the individual lived, which allowed the dealership to target his neighbors with advertising — this, on the theory that a man who could afford a car that expensive must live in a wealthy neighborhood. The marketers, according to my friend, were able to prove to the client that their methods had sold 13 more of these ultra-expensive cars than they had done in a comparable time period — a big success, given the rarity of this car brand, and how difficult it is to move products so expensive.

Mind you, all of this is completely legal. Marketers are coming up with new ways to make you want something without knowing that you want it. This is nothing new in advertising, of course, but what’s new is that they are now armed with an incredible array of private information about you and your preferences, based on someone mining your smartphone and your online profile for data.

You are not a person. You are a target.

The second form of tyranny, according to Askonas, is more straightforward. Excerpt:

Malicious actors, authoritarian regimes chief among them, are sophisticated adopters and promoters of the information revolution. How long ago were the halcyon days of the Arab Spring, when commentators could argue that Facebook and Twitter presented an existential threat to dictatorships everywhere. In reality, authoritarian regimes the world over quickly learned to love technologies that enticed their subjects into carrying around listening devices and putting their innermost thoughts online.

Big Brother can read tweets too, which is why China’s massive surveillance system includes monitoring social media. Slowing down Internet traffic, as Iran has apparently done, turns out to be an even more effective source of censorship than outright blocking of websites — accessing information becomes a matter of great frustration instead of forbidden allure. Before Russian troll farms were aimed at American Facebook users, they were found to be useful at home for stirring up anti-American sentiments and defending Russia’s aggressions in Ukraine.

By pulling so much of social life into cyberspace, the information revolution has made dissent more visible, manageable, and manipulable than ever before. Hidden public anger, the ultimate bête noire of many a dictator, becomes more legible to the regime. Activating one’s own supporters, and manipulating the national conversation, become easier as well. Indeed, the information revolution has been a boon to the police state. It used to be incredibly manpower-intensive to monitor videos, accurately take and categorize images, analyze opposition magazines, track the locations of dissidents, and appropriately penalize enemies of the regime. But now, tools that were perfected for tagging your friends in beach photos, categorizing new stories, and ranking products by user reviews are the technological building blocks of efficient surveillance systems. Moreover, with big data and AI, regimes can now engage in especially “smart” forms of what is sometimes called “smart repression” — exerting just the right amount of force and nudging, at the lowest possible cost, to pull subjects into line. The computational counterculture’s promise of “access to tools” and “people power” has, paradoxically, contributed to mass surveillance and oppression.

What’s shocking isn’t that technological development is a two-edged sword. It’s that the power of these technologies is paired with a stunning apathy among their creators about who might use them and how. Google employees have recently declared that helping the Pentagon with a military AI program is a bridge too far, convincing the company to cancel a $10 billion contract. But at the same time, Google, Apple, and Microsoft, committed to the ideals of open-source software and collaboration toward technological progress, have published machine-learning tools for anyone to use, including agents provocateurs and revenge pornographers.

It must be that the Silicon Valley people really do believe in their own good intentions. Askonas:

The counterculture’s humanism has long been overthrown by dreams of maximizing satisfaction, metrics, profits, “knowledge,” and connection, a task now to be given over to the machines. The emerging soft authoritarianism in Silicon Valley’s designs to stoke our desires will go hand in hand with a hard authoritarianism that pushes these technologies toward their true ends.

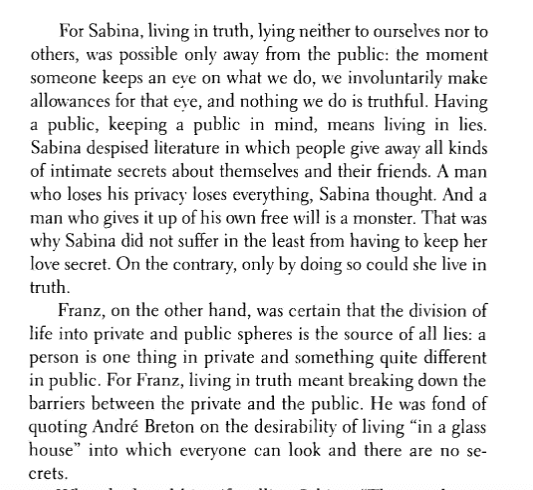

Finally, consider this passage from the 1980s novel The Unbearable Lightness of Being, by the Czech emigre novelist Milan Kundera. He’s writing here about two lovers, Franz and Sabina. Franz is Swiss, and lives in Western Europe; Sabina is a political exile from communist Czechoslovakia. They have contradictory views about privacy:

We who cherish our freedom are all going to have to learn how to be Sabina — this, in a world where the conditions of surveillance far surpass anything that the old communists carried out. The new order has convinced us to spy on ourselves, not just for the government, but for corporations. I’ll be in Bratislava and Prague at month’s end, interviewing people who grew up in the world that shaped Sabina. They have something valuable to teach us, I am convinced.