‘Ruthie Leming’ For Christmas

Anna-Liza Kozma of the CBC just published a beautiful review of The Little Way Of Ruthie Leming. Excerpt:

There is no more profound and irresistible question than to ask what it means to live a good life. The shadows of the greatest thinkers through the ages fall across the page of the writer who has the chutzpah to take it on. The Stoic philosophers, to whom I’m rather partial, boiled the good life pretty much down to: Pursue virtue; do good to those around you; and avoid causing harm. Doubtless Epictetus’ Discourses and Marcus Aurelius’ Meditations brought comfort and inspiration as the Romans rode into battle to conquer the known world, but we angst-ridden moderns tend to look for more full-bodied annunciations of goodness to get us through our own conflicted days.

And stories don’t come more full-bodied than Rod Dreher’s The Little Way of Ruthie Leming, which comes closer than almost anything I’ve read to lassoing the concerns and peculiar anguishes of 21st century men and women.

More:

I read this book three times and I wept each time. It wasn’t just the story of the three young girls left motherless – the pointlessness of Ruthie’s death, which might even have been prevented with an earlier diagnosis – though the book deals with this well. Ruthie’s eldest daughter, Hannah, sums up our creaturely ennui when she cries out to her uncle, “We’re here and then we die. What’s the point of any of it?” She had seen her good mother, who poured out her life for others – her pupils, her family, her friends – die young and in pain. How could a good and loving God – as her mother believed there is – allow this to happen? Dreher responds to his niece, and to us: “She didn’t try to understand the mystery. She just tried to live it. We have to try, too. There is no other way.”

No, it wasn’t the girls’ loss that I wept for. It was my own. Where is the good life to be found for those of us whose families are divided or itinerant or exiled? Those of us who have no homestead to return to? No generations of good deeds to cash in? Perhaps for us, for me, with family flung across various continents, the lesson from The Little Way of Ruthie Leming is a little different. We immigrants must find our community where we can. We are not to underestimate the value of digging in where we find ourselves. And church communities, with their intergenerational medley and potlucks and recurring liturgical rhythms, can be great places for transplants to root.

I am so grateful to Anna-Liza for that extremely generous review. And I am also grateful to find that Little Way made it onto the Christmas book lists of two men whose writing and thinking I respect greatly. At National Review Online, both Ryan T. Anderson and David French recommended the book:

Theology is meant to be lived, and Rod Dreher paints one picture of holiness — warts and all — in his moving tribute to his late sister, The Little Way of Ruthie Leming: A Southern Girl, a Small Town, and the Secret of a Good Life. [Anderson]

The Little Way of Ruthie Leming: A Southern Girl, a Small Town, and the Secret of a Good Life: I’ve placed Rod Dreher’s heart-rending masterpiece in the very short list of books that have changed my life. I reviewed the book for the dead-tree edition of National Review, expecting it to be a rather conventional story of one woman’s battle with cancer. Instead it’s a tonic to the Lean In ambition of our times, providing the reader with a sense of purpose and place as we live in and serve our own communities. [French]

If you would like me to personalize your copy of Little Way for Christmas, order through the website of Grandmother’s Buttons, a St. Francisville store. I live nearby, and don’t mind running over and writing whatever you like in the book. You have to pay for shipping, though — and I’m pretty sure quantities are limited. I’m talking with a Barnes & Noble in Baton Rouge about trying to do a signing there before Christmas. Stay tuned.

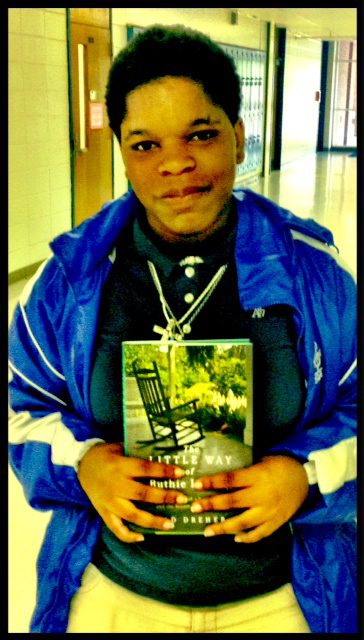

Some people are asking me to sign copies for a Christmas gift for their kid’s teacher. It’s not hard to see why. The girl in the photo above is Lyric Haynes, one of Ruthie’s former students. From Little Way, this account of how Lyric responded to news of Ruthie’s cancer:

Meanwhile, at the middle school, Ruthie’s class – the one that had been the worst-behaved of her entire career – had undergone a change of heart. At a school assembly, a girl named Lyric Haynes – a profoundly impoverished child whose mother was in prison, and who was one of Ruthie’s most challenging students – stood and made a short speech. All the teachers knew how hard Lyric’s life was, and how much courage it took for her to go before the entire school to make a presentation.

“This is about Mrs. Leming,” Lyric said. “As you all heard, Mrs. Leming has lung cancer. She always wants us to do good for ourselves, and make the right decisions. Now that she isn’t teaching here anymore, we are trying to make her proud.”

“She used to go head over heels for us, and now we are going to do the same for her,” Lyric continued. “Mrs. Leming, you are the best, and we love you very much. You will always be in our hearts.”

Ruthie loved that. She told me once on the phone that her cancer opened the door to experiences of others, and of their goodness, that she wouldn’t have otherwise had. “All this love,” she mused. “It’s unbelievable how blessed I am.”

And then, after Ruthie died:

Ruthie’s colleagues, most of whom I was just getting to know, wanted me to appreciate what kind of teacher she was. That night was the first I had heard of Lyric Haynes, the child whose mother was in prison, and who had read the speech about Ruthie at the school assembly after the cancer diagnosis forced her to retire.

When Ruthie died, the teachers worried that Lyric, now in high school, would lash out at others, and find herself back in the principal’s office for fighting. In fact, she only asked that someone take her back to the middle school, where Ruthie had taught her. She told them that she remembered the middle school as the place where teachers loved her. And she told them that she was going to do whatever she could to honor Mrs. Leming’s memory.

“If you really want to honor Mrs. Leming,” one teacher told her, “You will be good and study hard, and go to college to learn how to be a teacher. Then you can come back here to work, and help other kids the way Mrs. Leming helped you.”

“I’ll do it,” Lyric said.

I saw Lyric hours earlier at the wake, in the line passing by Ruthie’s coffin. I only figured her as one of the many former Ruthie students moving through the church that night. Until Ruthie’s teacher friends told me that night, I had no idea, no idea at all, of the drama of this child’s life, and the part my sister played in giving her love, and hope.