Purgatorio, Cantos XXII & XXIII

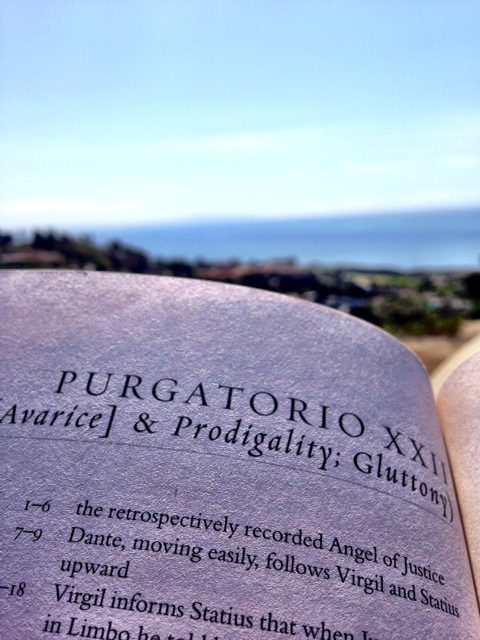

Our pilgrimage has been delayed for two days by my labors atop Mount Malibu, or whatever you wish to call the big hill overlooking the Pacific, on which Pepperdine University sits. Because we have fallen behind, I’m going to cover Cantos XXII and XXIII today. We have a lot of ground to cover.

As Dante, Virgil, and their new companion Statius, move through the terrace of Greed (from which Statius has just been liberated), Virgil begins again to instruct Dante:

“A love that is kindled by virtue

has always ignited another, as long as its flame

was shining where it could be seen.”

This is Virgil’s preface to asking Statius how he wound up on the terrace of Greed. Statius tells him that in fact, he was a big spender; the terrace punishes people who had a disordered love of money, either loving to hoard it or loving to waste it. Statius tells Virgil that he began to repent thanks to the wisdom in Virgil’s poetry.

Then Virgil asks him how he became a Christian (note well that the conversion of Statius is almost certainly a Dantean invention). Once again, Statius pays homage to Virgil, saying that it was he who first “lit my way to God.”:

“You were as one who goes by night, carrying

the light behind him – it is no help to him,

but instructs all those who follow –

“when you said: ‘The centuries turn new again.

Justice returns with the first age of man,

And new progeny descends from heaven.’

“Through you I was a poet, through you a Christian.”

In his Fourth Eclogue, Virgil, who died not long before Christ was born, prophesied the coming of a messianic figure. He was not talking about Jesus, but you can see how a later Christian could read that into Virgil’s lines. Marc at Bad Catholic says that the best way to regard Virgil’s lines is not to say that it’s obviously a prophecy of Jesus (though hey, it might be), or that it’s mere myth. Rather, there’s a third way:

Prophecy is often misconstrued as simply “telling the future.” Throughout history, however, those considered prophets just as often speak the truth about the present, going to tell the people that they are living in sin, worshiping false idols, etc. Prophets tell it like it is. Prophets tell the Truth.

So when Virgil writes a poem about a paradise lost, living in the hope of restoration by a hero, echoing and reechoing thousands of other stories from all over the world and all through time, his poem is a prophecy. Why? Because he tells it like it is. He names a truth tangible in human experience, that this world is imperfect and we wish it weren’t so, and creates a story where that tension is resolved.

The claim of Christianity is simply this: That the truth all humanity has been telling in their myths, that this world needs saving, has been resolved in the person of Jesus Christ.

In any case, it was Virgil’s authority, asserted through his poetry, that made Statius look to him for guidance; when Statius came to believe Virgil prophesied Christ, he sought out the company of Christians, at the time suffering persecution under Domitian. Statius says:

“Already all the world was pregnant

with the true faith, inseminated

by the messengers of the eternal kingdom,

“and the words of yours I have just recited

did so accord with the new preachers

that I began to visit them.”

I love the imagery here, of the world being made fecund through the words of the apostles and evangelists. For a poet to pay that kind of homage to a preacher is particularly meaningful. Statius goes on:

‘More and more they seemed to me so holy

that when Domitian started with his persecutions

their weeping did not lack my tears.’

Once again in the Commedia, we see art (the poetry of Virgil) and the saints (the early martyrs) testifying to God’s presence, and winning a convert. The poets and the prophets are more important than the logicians. But Statius hid his status as a Christian, a lukewarmness that earned him extra time on the mountain.

It’s painful to consider that Virgil, the pagan poet who has been the bearer of the salvific Good News to Statius and Dante, will not be able to join them in Paradise. Why not? Harriet Rubin writes:

To Dante’s eyes, Virgil made one mistake in life: he gave way to sorrow. Melancholy stands in the way of love’s transforming pleasures. It is Virgil’s tragedy. It is why he can save Dante, he can save Statius, but he cannot save himself.

More Rubin:

This is the ultimate lesson drawn from Virgil’s example. Even more than following the master poet’s words, it is clear to Dante that love draws out Virgil’s fear: love of a God he is not sure exists, or if he exists cannot return his love, even though that God may seem to answer his prayers.

I’m probably overinterpreting this, but this makes me consider the tragedy of my late sister and myself: that she loved family and place so much that she could save herself (so to speak), and she could save me by showing me the way home, but she could not save the future of our family. She refused to forgive and to accept me, something that seems so against her nature. Why? I think Dante, and Harriet Rubin, have given me some insight here: that love of family and place drew out my sister’s fear. Could she have been afraid that by forgiving me and accepting me in my exile from Starhill that she would in some sense approve of the path I had taken away from home — a path that she was afraid her own oldest daughter, Hannah, would take if she followed Uncle Rod’s bad example? Could this fear have caused Ruthie to refuse love?

On the walk, the three men, until they come to a strangely shaped tree. It is most likely a shoot from the Tree Of Life, from the Garden Of Eden. The tree is laden with savory-smelling fruits, and its leaves are watered from a high rock. The pilgrims hear a voice from within the tree calling, “This is a food that you shall lack.” Then the voice gives them three examples of Temperance. This is our signal that they have entered the terrace of Gluttony.

Early in Canto XXIII, the pilgrims hear weeping shades singing the words of Psalm 50: “Open my lips, O Lord, and my mouth shall proclaim your praise.” These are the penitent Gluttons, and are singing the Psalm to indicate a better use for their mouths than stuffing them with food and drink. Upon closer inspection, these shades look like refugees from a concentration camp:

Their eyes were dark and sunken,

their faces pale, their flesh so wasted

that the skin took all its shape from bones.

Dante marvels in horror at the physical wretchedness of these poor souls, and the intensity of their craving for the fruit and water of the Tree. Suddenly, one of them looks at Dante and cries: “What grace is granted to me now!”

Dante doesn’t recognize the skeletal man at first, but then it hits him: this is his old friend Forese Donati, utterly transformed by hunger. Dante demands to know why he looks so terrible. Forese explains:

“All these people who weep while they are singing

followed their appetites beyond all measure,

and here regain, in thirst and hunger, holiness.

“The fragrance coming from the fruit

and from the water sprinkled on green boughs

kindles our craving to eat and drink,

“and not once only, circling in this space,

is our pain renewed.

I speak of pain but should say solace,

“for the same desire leads us to the trees

that led Christ to utter Eli with such bliss

when with the blood from His own veins He made us free.”

For me, these are among the most beautiful passages in the entire Commedia. Here is a man who is starving — starving! — and yet, he and his fellow penitents take comfort in their sufferings, having joined them to Christ’s, knowing that the pain of their renunciation of appetite takes them closer to union with God. The paradox here: the bliss of agony, the agony of bliss. They hunger for the Bread of Heaven.

If we could fast just one hour with the intensity that Forese fasts, how much closer to God would we draw?

If we knew with all our heart that our pain and suffering could purify us, would we run from it with such desperate vigor?

I think about this. I think about this a lot. The first time I read the Purgatorio, I learned in this canto, by entering the imagination of the starving but ecstatic Forese, how I should rightly order the pain in my own heart over the failures of love, so that they would be transformed into a deeper, stronger love. But to know how to do it and to do it are not the same thing. Like Forese, I think I will be on this terrace for some time yet. I am a glutton for food and drink, no doubt, but I am also a glutton for other things that I cannot have. Purging myself of those cravings, of those disordered appetites, began with the repentance I made last fall, after finishing the Purgatorio, but it must be renewed every day, it seems. Forese made an idol of food and drink, and set his appetite on acquiring them. So do I. I can’t be sure why — probably because a sharp and insistent appetite for food and drink is my besetting sin — I understood in these cantos, on this terrace, the nature of all disordered desire. It was there that I grasped that I had made an idol of the approving love of my family in Louisiana — my father and my sister, to be specific. I hungered so intensely for it, and, I discovered here, made it more important to me than the hunger for God. I didn’t know it till it was revealed to me on this pilgrimage up the mountain, but I came home expecting to find the fatted calf slain and prepared for a banquet. It wasn’t there. It was only by circling in the space of daily life these past two years, pushing forward ravenously through chronic illness and depression, that I was able to unhitch myself from the reins of illusion, and begin to seek, at last, the only Source of real hope.

I had thought my return home was entering into the Promised Land, but in fact I was circling back to Egypt, in my heart. It was this canto that turned me around, and pointed me toward my true and only home. It was this canto that first gave me reason to think that the suffering I was enduring last year were the necessary prelude to bliss — a bliss that had eluded me all my life, because I had supremely loved the wrong thing. St. Augustine was right: my heart would be restless until it rested in God, who is Love. Only God is god. Not family. Not place. Eating stones for two years had broken my teeth and starved me down to the bones — but like a drought dries up a lake and uncovers hidden structures long obscured by the water, the intense pain of that unslakable thirst and hunger that could never be satisfied sharpened my inner vision, and revealed to me structures of sin deep within my heart. Only by clearing them away through repentance could I mount the path to the true Tree of Life, which is the Cross.

I gained this self-knowledge at an at-times excruciating price. But now, because of the freedom it brought me, I regard that purgation like Forese did: as a solace.

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.