Oskar Schindler’s Factory

Earlier this week, I thought I would go out to visit Auschwitz today. The town of Oswiecim is about an hour and a half from Krakow, and there are lots of tour buses headed there. Yesterday, though, I was warned against it by a couple of people in Krakow. They said that I absolutely should go, but that I should be aware that nothing can prepare you for it — especially the massive scale of the death factory. Because I have to be prepared to lecture at a Benedictine abbey this weekend, my friends said that I would be taking a risk by going to Auschwitz. It could take me some time to recover. One of my friends said that she speaks from painful personal experience.

“Go next time you’re here,” she said. “And if you can, go with a loved one.”

Instead, I went today to visit Oskar Schindler’s factory in Krakow, which the city has turned into a museum memorializing the experience of Krakow under Nazi occupation (1939-1945). If you’ve seen Schindler’s List, you know that he was a minor Nazi industrialist who ended up saving the lives of about 1,200 Jews by employing them in his Krakow enamel factory. When the Nazis began liquidating the Krakow Jewish ghetto, Schindler devoted himself to protecting his Jewish workers. Schindler used his Nazi insider connections, and paid extensive bribes, to keep them alive. By the war’s end, Schindler had exhausted his fortune on his mission of mercy. He is the only Nazi Party member buried with honor on Mount Zion in Jerusalem.

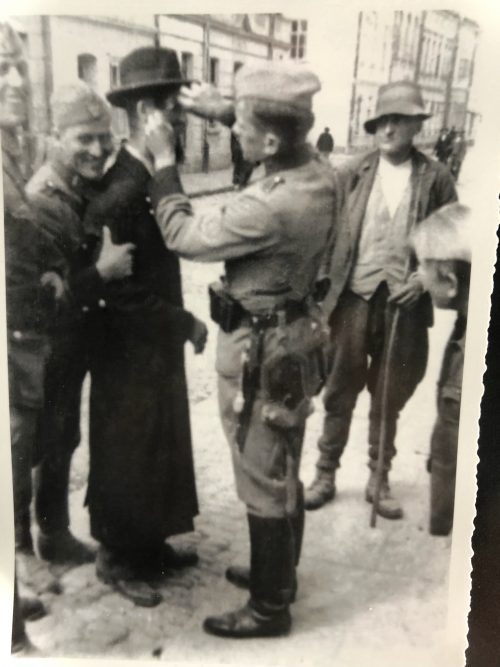

When they conquered Poland, the Nazis established their headquarters for the “General Government,” their term for German-occupied Poland, in Krakow. They turned on the city’s large Jewish population at once. Here is a photo from the museum showing German soldiers amusing themselves by shaving a Jew’s sidecurls and beard:

The governor was Hans Frank, Hitler’s personal lawyer and an occultist. He wrote in 1941:

A great Jewish migration will begin in any case. But what should we do with the Jews? Do you think they will be settled in Ostland, in villages? We were told in Berlin, ‘Why all this bother? We can do nothing with them either in Ostland or in the Reichskommissariat. So liquidate them yourselves.’ Gentlemen, I must ask you to rid yourself of all feelings of pity. We must annihilate the Jews wherever we find them and whenever it is possible.

In the museum, you turn a corner and see these … and it stops you cold:

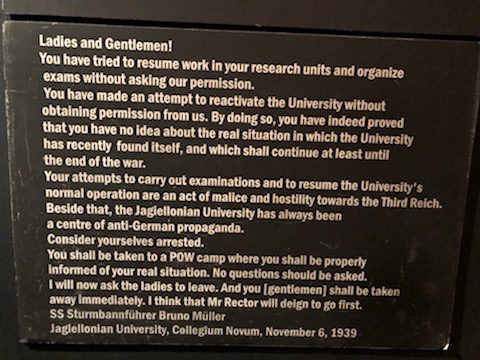

And there’s this on the wall, from one of Hans Frank’s deputies, in his statement announcing the closing the Jagiellonian University:

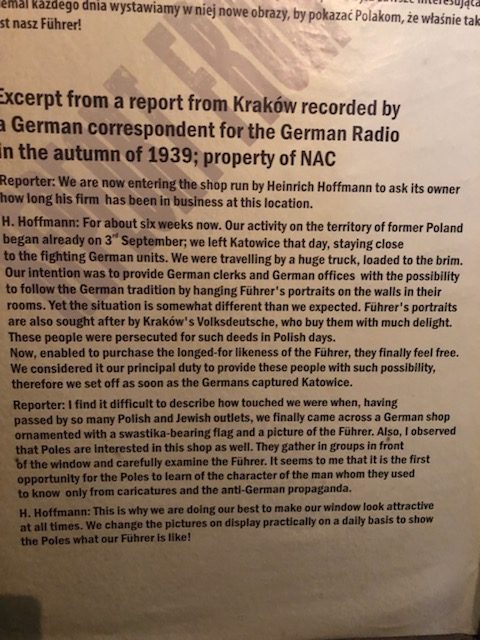

More — this from a German radio propaganda broadcast proclaiming the glories of life for ethnic Germans in Nazi-occupied Poland:

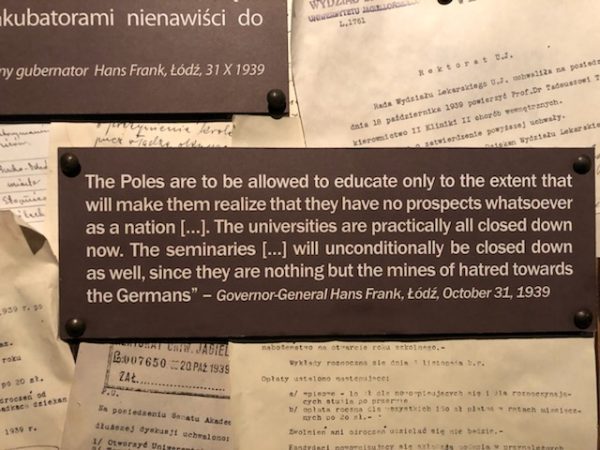

The Nazis wanted to eliminate all cultural memory of the Poles as a people, to grind them down into slaves:

The Jews they simply wanted to murder … but not straightaway. Here’s what the entrance to the Krakow ghetto looked like:

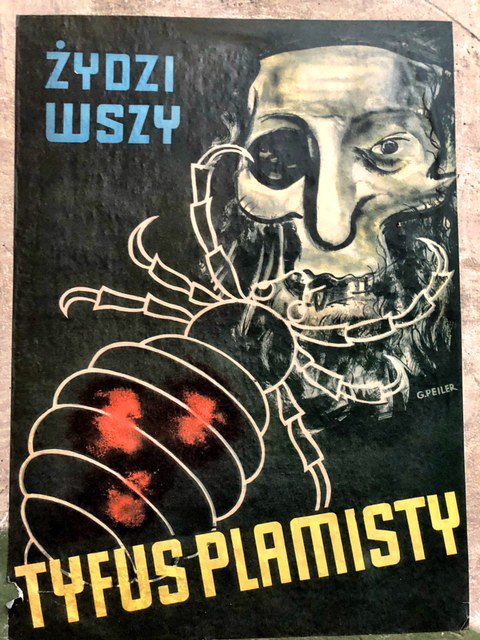

A Nazi propaganda poster proclaiming that Jews spread typhus:

It’s a kind of pun in Polish, saying that “there are lice called typhus”; “Zydzi wyzy tyfus” (without “plamisty”) means “there are all typhoid Jews.”

I didn’t have any great epiphanies in this museum. The effect was jarring, though: to come face to face with extreme evil — and this wasn’t remotely Auschwitz! I left the Schindler factory grateful that my friends had warned me about what confronting the great evil of the concentration camp would likely do to me. The reality of human evil is excruciating to face. Those are banal words, I know. But I tell you, having walked down the beautiful, charming streets of Krakow’s old town on my first day here, and then going to this museum and seeing film and photographs of Nazi soldiers parading in the same spaces — man, that shakes you up.

(A practical note for visitors to the Schindler factory: get your tickets in advance, online; they only let a certain number of visitors in at a given hour, to keep it from being too crowded.)

In the museum, I learned that “Schindler’s Jews” lived incredibly punishing, difficult lives, but they were the luckiest Jews of all — not just because they survived, but also because as hard as their lives were, they had it better than all other Jews living under Nazi terror.

I have long believed that the Holocaust was the most important event of the 20th century. It proves that no matter how culturally and technologically sophisticated we may be, we can revert to rank barbarism overnight. Solzhenitsyn warned readers of The Gulag Archipelago to be aware that what happened in Russia could happen anywhere on earth. It’s also true about what happened in Germany … and in Nazi-occupied Poland.

Let me end by saying that anybody who seriously compares what is happening anywhere in America today — however bad it may be — to what the Nazis did to Jews and others they hated should be ashamed. Just stop. Don’t go there. We have to keep the language for extreme evil like this pure, so what the Nazis did does not lose its power to shock the conscience.