Maybe Let’s Not Abolish The Police

Faizel Khan was being told by the news media and his own mayor that the protests in his hometown were peaceful, with “a block party atmosphere.”

But that was not what he saw through the windows of his Seattle coffee shop [located in CHAZ — RD]. He saw encampments overtaking the sidewalks. He saw roving bands of masked protesters smashing windows and looting.

Young white men wielding guns would harangue customers as well as Mr. Khan, a gay man of Middle Eastern descent who moved here from Texas so he could more comfortably be out. To get into his coffee shop, he sometimes had to seek the permission of self-appointed armed guards to cross a border they had erected.

“They barricaded us all in here,” Mr. Khan said. “And they were sitting in lawn chairs with guns.”

More:

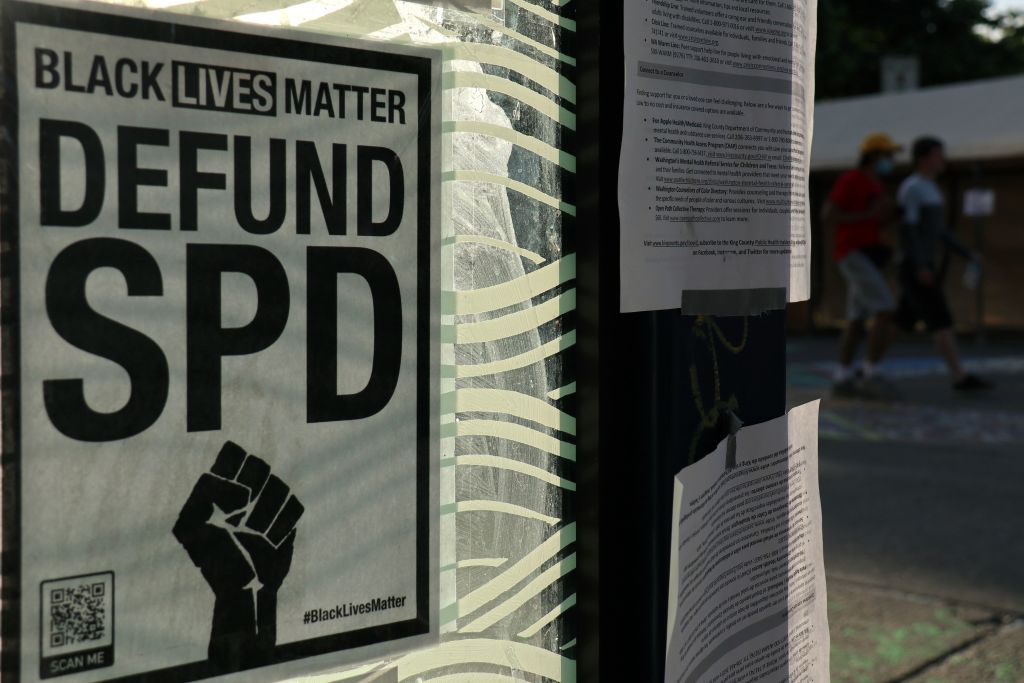

Leaders in many progressive cities are listening. In New York City, Mayor Bill de Blasio has announced a plan to shift $1 billion out of the police budget. The Minneapolis City Council is pitching a major reduction, and the Seattle City Council is pushing for a 50 percent cut to Police Department funding. (The mayor said that plan goes too far.)

Some even call for “abolishing the police” altogether and closing down precincts, which is what happened in Seattle.

That has left small-business owners as lonely voices in progressive areas, arguing that police officers are necessary and that cities cannot function without a robust public safety presence. In Minneapolis, Seattle and Portland, Ore., many of those business owners consider themselves progressive, and in interviews they express support for the Black Lives Matter movement. But they also worry that their businesses, already debilitated by the coronavirus pandemic, will struggle to survive if police departments and city governments cannot protect them.

This is interesting:

Many are nervous about speaking out lest they lend ammunition to a conservative critique of the Black Lives Matter movement. In Portland, Elizabeth Snow McDougall, the owner of Stevens-Ness legal printers, emphasized her support for the cause before describing the damage done to her business.

“One window broken, then another, then another, then another. Garbage to clean off the sidewalk in front of the store every morning. Urine to wash out of our doorway alcove. Graffiti to remove,” Ms. McDougall wrote in an email. “Costs to board up and later we’ll have costs to repair.”

Yeah, lest they themselves start connecting the dots and having Unwanted Conclusions about the Black Lives Matter movement, and what it has become. These progressives mugged by reality might become conservatives, and then their lives would be over, I tell you, over. I predict that they will mount a heroic struggle to maintain cognitive dissonance.

I do not dispute that the police, broadly speaking, need to be reformed. Breonna Taylor died as the result of police executing a no-knock search warrant. How can we justify no-knock warrants? If somebody burst into my house unannounced in the middle of the night, you can bet that I’m going to come out of my bedroom shooting. I was pleased to see that the Louisville police chief suspended the use of no-knock warrants in the aftermath, but I would like to see them banned nationwide. That’s just one reform that could happen; there are others. I find it deeply regrettable that the outrageous police shooting of Breonna Taylor has been racialized by activists. She was an innocent person who died because of aggressive and unjust (though probably legal) police action. Unless there’s evidence that Louisville police only used no-knock warrants on black people, I can’t understand why her death has to be racialized. No-knock warrants are a danger to everyone. (If there’s something about this case that does make it racial, please educate me on it.)

But reforming the police is not the same thing as abolishing the police. In fact, Gallup this week released some very interesting poll findings. Take a look:

When asked whether they want the police to spend more time, the same amount of time or less time than they currently do in their area, most Black Americans — 61% — want the police presence to remain the same. This is similar to the 67% of all U.S. adults preferring the status quo, including 71% of White Americans.

Meanwhile, nearly equal proportions of Black Americans say they would like the police to spend more time in their area (20%) as say they’d like them to spend less time there (19%).

Gosh, it’s almost as if the views of activists, journalists, and commentators in the national media are not the same as views of actual black people who live under the oppression of crime.

Anyway, all credit to New York Times reporter Nellie Bowles for that complex, detailed report. I really do urge you to read it, to learn what the ordinary business people, of all races, had to suffer under CHAZ, which the Seattle city government permitted to terrorize residents of Seattle’s Capitol Hill neighborhood.

I want to say one more thing about the two posts I had up earlier this week about how the new police bodycam footage from the George Floyd incident made me question the received narrative about what happened to Floyd. (First post here, second post here.) I do not think that the new footage necessarily absolves the police officers of criminal wrongdoing, or even moral fault, in Floyd’s death — that remains to be seen in the criminal trials — but they do add much-needed context for what led to the neck restraint under which Floyd died. As I wrote earlier this week, I had made assumptions about both Floyd and the way he died that turned out on second examination (prompted by the new videos) to be far too simplistic. If you read those blogs and/or Twitter this week, you saw that that did not go over well with a lot of people.

This morning I was thinking about that, and recalled a conversation I had a few years back with an ex-cop after the Alton Sterling shooting here in Baton Rouge. That was a racially charged event in which two white city police officers got into a scuffle with a black man outside a convenience store, and shot him dead. My ex-cop friend is no longer a cop in part because he became disgusted with the brutality of doing his job. That is, with the overall brutality that even good police officers have to deal with as part of their job, but also with police brutality that crosses legal and moral lines. My point is, this ex-cop is especially sensitive about police brutality. Well, the ex-cop walked me through security cam footage, frame by frame, analyzing what the officers did, what Sterling did, and what it meant. His conclusion was that the officers could have done things differently, and maybe had a different outcome, but they had done nothing wrong, and that Sterling really had reached for the gun of one of the officers he had pinned to the ground. The ex-cop told me that these officers would likely not be charged, and if they were, they would probably be acquitted, because they had followed established procedure.

Sure enough, after a lengthy investigation by the Obama-led US Department of Justice, no charges were brought. A subsequent state investigation had the same result.

It was eye-opening to me to be shown the Sterling video and guided through it with the eyes of a trained law enforcement professional, particularly one known to me as someone who would not be naturally sympathetic to the police in brutality cases. It taught me how little people outside that world understand about police procedure, and how we can’t rely wholly on our own untutored eyes to tell us fully and accurately what we are seeing in cases like this. This is why we should be grateful for our dispassionate legal system, flawed though it may be. What feels true, and what is true, are often two different things.

My brother in law is a firefighter in Baton Rouge. A few years ago, I used to have the chance to talk to firefighters every now and then, because of that connection. I found myself in a conversation with one of them once, on the subject of police brutality. He said that in his work — at the time he was stationed in a poor black part of town, one of the most violent districts in the city — he has seen police officers, both white and black, treat civilians in a less than ideal manner. It bothered him. But, he added, it’s hard for people who don’t live or work in those neighborhoods to understand how violent everyday life is for the people who live there. The middle-class idea of stability and structure is completely alien, this man told me.

He gave me an example of something he saw with his own eyes. They got a call one night on a domestic disturbance. A woman had been badly beaten by her male partner. Because there was a medical aspect to the call, the firefighters had to go too, as well as the police. Both the woman and her alleged attacker were black. The firefighter told me that the woman was in bad shape. The police were so shocked by it that one of the cops — a black officer — started manhandling the black suspect. The black officer was so disgusted that a man could do that to a woman that he cut loose on the suspect. It was wrong, said the firefighter, but seeing how badly beaten the woman had been, he could understand how that black cop lost control.

And yet, said the firefighter, the beaten woman would not cooperate with the police, and would not press charges against the man who so badly beat her. Sadly, that happens in domestic violence cases, and is why bad men often get away with it. The firefighter explained, though, that the code of Never Cooperate With Police is very powerful in that poor black community, to the point where some people would rather take beatings than be seen helping the police. My sense was that the firefighter — a white man — was trying to convey to me how difficult it is to police those communities, and how violence and disorder are so deeply a part of the community’s life that it defies the ability of middle class people to comprehend.

I emphasize strongly: the firefighter was not justifying any of this! He was only saying how his own experiences as a bystander to many of these encounters between police and civilians in that poor black part of the city taught him that most outsiders don’t understand the complex and tragic dynamics there. This was years ago, probably in the aftermath of the Sterling shooting, but the sense that stayed with me of this conversation was that the white man, who was born and raised and lived in the suburbs, was finding that the longer he worked in the inner city, the less he understood human nature.

I wonder what people like that are thinking and saying these days. Well, if they’re white, they’re not talking on the record, and maybe not off the record. The price could be your job. If they’re black, maybe they’re not talking either, because the pressure within their own communities to hold to the eff-the-police narrative could be strong. But when you’re speaking anonymously to a pollster, you are more free to say what you think. Most black people in America are happy with the police presence in their communities, and a significant minority wish the police would spend more time there. Only one in five black Americans want less police presence in their communities.

That same poll, note well, finds that fewer than one in five black Americans are confident that if they encountered police, that police would treat them with courtesy and respect. That’s a shocking number that reveals a lot of work to be done to build trust. Black people, overall, want police in their neighborhoods, but they want to have confidence that they will be treated decently by them. Those citizens deserve to have that confidence. We all do.

The point here is that there is a greater middle ground on the question of policing and racism than you would think from the general narrative promulgated by the national media. That powerful Times story today about how those racial activists, especially white antifa members, bullied and even brutalized shopkeepers and others in CHAZ, is exactly the kind of complexifying story we need to read to give us a more complete picture of what’s happening in America now.

Given the documented fact that US media has given itself over dramatically to a far-left Critical Race Theory framework for reporting on and interpreting race in America, I don’t know how likely we are to see those stories. But today’s Nellie Bowles piece in the Times is a welcome counterexample.

One last thing: I’ve been texting last night and this morning with a white friend who is a middle-class professional today, an observantly Christian family man, but who grew up in Section 8 housing. He finds himself frustrated by Republicans, for the usual reason, but really repulsed by middle-class liberal discourse (and middle-class Christian discourse) about crime, poverty, and race. He tells me that he knows perfectly well how violent and chaotic poor neighborhoods often are, because he grew up in one — and again, he’s white. He says, “I want my children around non-dangerous people of whatever color, and away from chaos and crime. Every parent wants that.”

He thinks both professional liberals and professional conservatives are usually full of crap, because they don’t know what it’s like to live around poor people. The poor — the black poor, but also all the poor — become not real people, in all their humanity, but rather screens onto which others project their ideals, their fears, and their hatreds. I grew up not in poverty, but around a significant amount of rural poverty, so it’s not as easy for me to do this as it is for some people, but still, I am sure that I do it. This is something I need to work to overcome.

The thing that middle-class people assume is normal is Order. Poor people don’t have that luxury. My wife’s father told a story about how years ago, when the black pastor Tony Evans (whom he used to know) came to south Dallas, Pastor Evans and his wife set up a program for the children of the church. They let the kids come over to their house after school, so they could do their homework and be safe while their parents were still at work. According to my father-in-law, the pastor and his wife were shocked to find their house full of kids who would come in from school and fall sound asleep on the floor. Day after day.

Eventually they discovered why: these kids, all of them poor or at least economically distressed, lived in such chaotic circumstances that when they got to a safe, well-ordered place (their pastor’s house), they were able to let down their guard, and sleep. Something that middle class people take for granted was for those poor children a luxury only made possible by the kindness of their new pastor.

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.