The Light In The Christchurch Darkness

I had to drive up to St. Francisville today, and on the way, continued listening to Jordan Peterson’s YouTube lecture on the book of Genesis. Peterson comes at the text not as a theologian, but as a psychologist. It’s a fascinating perspective. He believes that the great myths tell us something truthful about human nature, and about reality itself.

At some point, between errands, I stopped listening to Peterson and checked out the afternoon NPR newscast. I heard Rob Schmitz, who has been in New Zealand for a week covering the aftermath of the mosque shootings, talking about what he has seen and heard. I can’t find online a text of the back and forth between Schmitz and the “All Things Considered” anchor, but at some point, Schmitz was talking about visiting one morning a mosque that had not been attacked, and being met at the door by a man named Abdul who invited him in to have breakfast with the community.

Today, standing outside a mass funeral for many of the victims, Schmitz said he saw Abdul in the crowd. Abdul came over to him, gave him a big hug, and said, “I love you, brother.” Schmitz said he had succeeded all week in keeping his emotions in check while covering the story, but in that moment, he broke down.

It was an incredibly moving moment. I couldn’t help thinking of the Amish people who, back in 2006, embraced the grieving and humiliated mother of the deranged man who murdered five of their children before killing himself. How do people find it within themselves to do things like that? How do people find it in their hearts to say things like Farid Ahmad said? Excerpt:

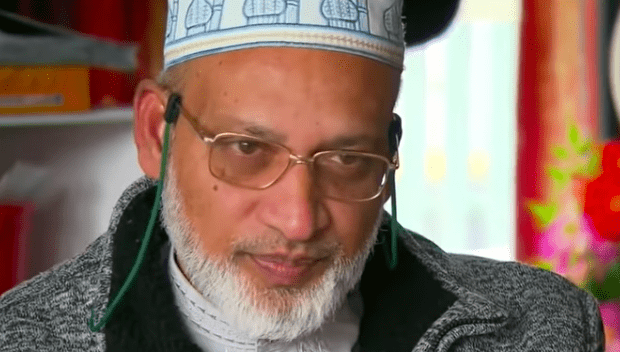

A man whose wife was killed in the Christchurch mosque attack as she rushed back in to rescue him said he harbours no hatred towards the gunman, insisting forgiveness is the best path forward.

“I would say to him ‘I love him as a person’,” Mr Farid Ahmad told AFP.

Asked if he forgave the 28-year-old white supremacist suspect, he said: “Of course. The best thing is forgiveness, generosity, loving and caring, positivity.”

It is only by divine grace that they can. I would love to think that I could react the way those Christchurch Muslims, and the Amish from 2006, did if I suffered that kind of traumatic loss, but I know myself well enough to know that it would take everything I had simply to hold myself together and keep from falling to pieces. Offer someone else forgiveness? Tell a stranger I loved them? Embrace the humiliated and broken family of the man who murdered my child? It is very hard for me to make the leap of imagination necessary to do that. I hope that if, God forbid, I find myself in a situation like that, that I get out of my own way and let the grace of God work through me.

This terrorist sought to tear our nation apart with an evil ideology that has torn the world apart. But, instead, we have shown that New Zealand is unbreakable. And that the world can see in us an example of love and unity. We are broken-hearted but we are not broken. We are alive. We are together. We are determined to not let anyone divide us.

We are determined to love one another and to support each other. This evil ideology of white supremacy did not strike us first, yet it has struck us hardest. The number of people killed is not extraordinary but the solidarity in New Zealand is extraordinary.

To the families of the victims, your loved ones did not die in vain. Their blood has watered the seeds of hope. Through them, the world will see the beauty of Islam and the beauty of our unity. Do not say of those who have been killed in the way of Allah that they are dead. They are alive, rejoicing with their Lord.

I don’t believe that Islam is true, but I was thinking today, listening to Rob Schmitz’s account of being with the Islamic mourners, and that man Abdul who said, “I love you, brother,” that these people offer powerful witness to the Islamic faith. Islamic terrorists and others (e.g., Pakistani anti-Christian bigots) who do cruel and destructive things in the name of their faith obviously offer a terrible witness to Islam, but when you see religious believers doing something extraordinarily good in the name of faith, especially when every natural and reasonable impulse within you says not to do that thing — well, it’s a powerful thing. It could convert people.

I bring this all up in light of this passage from Jordan Peterson’s lecture, at the 1:06 point. Just click it; I have it cued to the precise moment. Watch it for at least three minutes:

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hdrLQ7DpiWs?start=3960]

What Peterson says, in a nutshell, is that we are all drawn to people who adopt a “mode of being” that gives them the power to live through catastrophes and affirm life anyway. We know that it could be otherwise, that we could choose to live in such a way that makes what is bad even worse. Those who choose the other path are people that we are drawn to from the depths of our being.

It sounds like a banal thing, but if you watch the entire lecture, it is really quite profound. Peterson connects this kind of response to suffering to the creation of the cosmos. He explains how, according to Genesis, God brought light to darkness, and ordered chaos. God used his power to bring harmony to that what was scattered. This, he says, is the power that we human beings have. We can choose to order, or we can choose to scatter. We can choose to live in harmony with each other, with the world, with being — or we can choose to live diabolically: to hurt, to scatter, to increase the world’s chaos and pain. This is an awesome responsibility, one that we cannot escape.

You know that famous line from one of Dostoevsky’s characters, the one you see on bumper stickers? It goes: Beauty will save the world. I was thinking not long ago, when I was visiting that Orthodox monastery in upstate New York, about that saying, and what it might mean. The poet and literary scholar James Matthew Wilson has some deep reflections on the meaning of beauty, thoughts I keep going back to again and again. I strongly recommend his book The Vision Of The Soul: Truth, Goodness, and Beauty In The Western Tradition. But tonight, I’m thinking of this post I put up in 2015 about some of his earlier writing and teaching about the nature of beauty. Here’s JMW:

A work of art’s integrity is its internal wholeness, and its proportion is its fitting relation to a potentially vast order of things part of and beyond itself. Clarity marks the proportion of a thing to our intellect, as Eco appreciates, but it also draws our intellect into luminous relation with the whole intelligible order of reality that proceeds from Beauty Itself. The work of art, in its beauty, therefore stands between the perceiving and the creative intellects, drawing the former toward the latter. We are oriented by beauty into the whole harmony of the cosmos; the individual artwork draws us toward a vision of the truth, goodness, and order of things.

More:

We can, after all, make an error in a math problem, but the judgment of the beautiful and the ugly can be instantaneous and irrevocable–even if it also develops and deepens gradually as the proportions of a thing unfold before our intellects. One can soften truth claims with qualifications and ethical judgments by couching them as kind reminders and positive enticements. But when a work of art is set before us to declare the lordship of God, as do, for instance, the churches of the high Middle Ages, there can be no such hesitation: as soon as we perceive a proportion as beautiful, it takes hold of us as much as we do of it.

Of course, the millions of tourists who visit Notre Dame or Chartres may beg to differ. They would tell us that they come for the beauty of the architecture, not for the Gospel in stone it claims to preach. But I can only reply, “It is the force of that Gospel already working within you. You cannot deny the presence of beauty; you sense its orderliness calling you to an order beyond itself but of which it is a part.”

Now, JMW is talking about works of art, not moral acts. In fact, JMW writes:

Aquinas appropriately emphasizes that beauty is distinct from goodness precisely because, where goodness leads us to the pleasure of possession, “beautiful things are those which please when seen.” The measurement of arithmetic concludes primarily in a true answer; but it and other measures may also be such that, when we see the way in which they fit together, we are pleased. Beauty’s root in the form is no understatement: we encounter beauty precisely when we see the form of a thing and how it fits within a larger harmony and order comprising other things. Beauty therefore designates an aspect of reality. It is ontological, and no less so because part of its reality may be its relation to the perception of a knowing subject.

Don’t you think, though, that witnessing from afar acts like those Muslims forgiving the killer, or showing love to strangers even amid their mourning, or the Amish doing what they did — don’t you think those profoundly moral acts also have about them an aesthetic quality, in that they draw us away from chaos and destruction, and towards the “larger harmony” of the God-created, God-saturated cosmos? When a human being performs an act that restores harmony and order and life to a reality that has been scattered and deadened by an act of evil, is this not a theophany, a revelation of the God who orders all things, and who declared his creation to be good?

The Muslim who publicly forgave his wife’s killer does not profess Jesus Christ, but that man is made in the image of God by virtue of his humanity, and, following Prof. Wilson, that Muslim man’s act stirred the force of the Gospel already working within me. I cannot deny the presence of beauty in what that Muslim man did — not just goodness, but beauty — and sense its orderliness calling me to an order beyond this bloody and cruel world. Here is the opening of the Gospel of John (verses 1-5), in David Bentley Hart’s gripping, idiosyncratic translation (He uses “GOD” where the original Greek uses “o theos,” referring to God in the fullest sense, and “god” where the Greek uses only “theos”.):

In the origin there was the Logos, and the Logos was present with GOD, and the Logos was god; This one was present with GOD in the origin. All things came to be through him, and without him came to be not a single thing that has come to be. In him was life, and this life was the light of men. And the light shines in the darkness, and the darkness did not conquer it.

As Hart writes in the essay accompanying his recent translation of the New Testament, the term “logos” has far more philosophical depth than the word we usually use in this passage, “Word”. It means “ordering principle,” “reason.” For Christians, it is God’s revelation of Himself active in creation. Jesus wasn’t just a symbol of the Logos; he was Logos, though also separate from God the Father. This all has to do with Trinitarian theology, and there’s no need to get into it here on this already too discursive blog post. My point is simply this: When people respond to catastrophic evil by showing love, in all its manifestations, the light shines in the darkness, and the darkness does not overcome it. They are meeting chaos with order, ugliness with beauty. Whether or not they know what they’re doing, they are revealing the Logos, who is Jesus Christ.

A Muslim (or a Buddhist, or any non-Christian) would of course disagree that his act of love reveals Jesus Christ, just as I would deny that the same act reveals Allah, or the Buddha-nature, or whatever. That’s fine — it’s an important argument, but not as important as the fact that for whatever reason, the chaos and darkness Brenton Tarrant brought into the world last week did not have the last word, and it did not have the last word because those Muslim people in Christchurch chose not to let it have the last word.

I’ve got to say, this is inspiring to me, and not just because it’s an example of what the social psychologist Jonathan Haidt calls “elevation”. I’ve been struggling with some difficult problems in my own life, though nothing remotely as difficult as what the survivors and mourners of Christchurch are dealing with. Still, it’s not nothing, and there are a lot of times when I wonder where God is in all this. Then I observe from afar acts of uncanny beauty and goodness amid immense pain and suffering, and I think, Oh, that’s right, He’s there. He’s here. There is meaning here, and that meaning is love, despite what it might seem like at the moment. Look, there it is, revealing itself in Christchurch, in the words and deeds of Muslim mourners.

This is how beauty will save the world.

Anyway, that’s what I’ve got for you tonight. May the memory of those killed in New Zealand be eternal. Those who mourn them are not Christians, but they have made the meaning of their city’s name — “Christchurch” — resonate powerfully, at least in the heart and the mind of this Christian. If there’s one thing that the Gospels tell us, it’s that God will manifest Himself where we least expect him to do so.

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.