Europe’s Open Southern Borders

Everything Christopher Caldwell writes is a must-read, I find. Here’s a piece about the massive demographic challenge facing Europe this century, and about how elites there don’t want to face it. Excerpts:

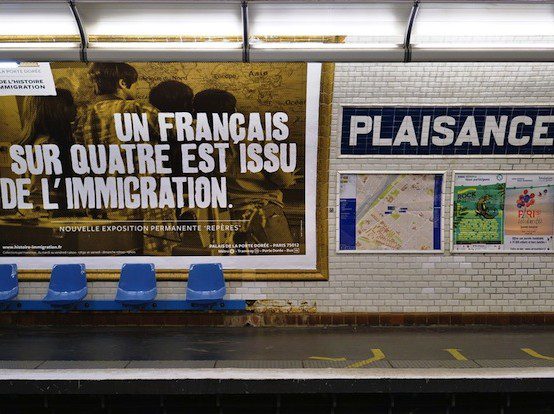

The population pressures emanating from the Middle East in recent decades, already sufficient to drive the European political system into convulsions, are going to pale beside those from sub-Saharan Africa in decades to come. Salvini owes his rise — and his party’s mighty victory in May’s elections to the European Union parliament — to his willingness to address African migration as a crisis. Even mentioning it makes him almost alone among European politicians. Those who are not scared to face the problem are scared to avow their conclusions.

Last year Stephen Smith, an American-born longtime Africa correspondent for the Paris dailies Le Monde and Libération, now a professor of African and African-American studies at Duke, published (in French) La ruée vers l’Europe, a short, sober, open-minded book about the coming mass migration out of Africa. The most important book written until then on the subject, it quickly became the talk of Paris. It has now been published in English.

Smith begins by laying out some facts. Africa is adding people at a rate never before seen on any continent. The population of sub-Saharan Africa alone, now about a billion people, will more than double to 2.2 billion people by mid-century, while that of Western Europe will fall to a doddering half billion or so. We should note that the figures Smith uses are not something he dreamed up while out on a walk — they are the official United Nations estimates, which in recent years have frequently underestimated population shifts.

The closer you look, the more disorienting is the change. In 1950 the Saharan country of Niger, with 2.6 million people, was smaller than Brooklyn. In 2050, with 68.5 million people, it will be the size of France. By that time, nearby Nigeria, with 411 million people, will be considerably larger than the United States. In 1960, Nigeria’s capital, Lagos, had only 350,000 people. It was smaller than Newark. But Lagos is now 60 times as large as it was then, with a population of 21 million, and it is projected to double again in size in the next generation, making it the largest city in the world, with a population roughly the same as Spain’s.

Caldwell writes that Smith’s book explores the tragedy of European investment to build up African industries, to deter Africans from wanting to migrate. It turns out that getting a little bit of money in their pockets actually works as an incentive to Africans to migrate. More:

The most serious heresy in Smith’s book is this: The extraordinarily disruptive mass movement of labor and humanity from Africa to Europe, should it come, will bring Europe no meaningful benefits. Narratives of Europe’s enrichment by migration are post facto rationalizations for something that Europe is undergoing, not choosing. Europe does not need an influx of youthful African labor, Smith writes, because both robotization and rising retirement ages are shrinking the demand for it. Migrant laborers cannot fund the European welfare state. In fact, they will undermine it, because the cost of schools, health, and other government services that philoprogenitive newcomers draw on exceeds their tax payments. Nor will the mass exodus help Africa. It will sap the rising middle class in precisely the countries — Senegal, Ghana, Côte d’Ivoire, Nigeria, Kenya — with the best chances for economic success.

Caldwell goes on to talk about how Smith, who lived in Africa for many years, and worked as a correspondent for Paris’s left-wing daily, has been calumniated by French elites as some sort of rightist who doesn’t have the right to offer an opinion. Says Caldwell: “European political issues, like American ones, are increasingly matters of “values” and “rights” — whatever you call them, they are not up for negotiation.Read it all.

This week, Italy’s Matteo Salvini declared victory after a migrant boat he refused to let dock in his country received a Spanish offer of haven. He said, “Italy is not the refugee camp of Europe.” A Pyrrhic victory: other European countries have offered to resettle the refugees. They will have managed to get to Europe after all.

And remember, the migration from the South has barely begun. We’re not supposed to mention the name of Jean Raspail, who wrote the dystopic anti-migrant novel The Camp of the Saints, but I can’t think of a better summary of the tragedy facing Europe this century. I can’t find the precise quote, but it was something like this: “Either we accept this invasion, and we cease to be who we are. Or we take the necessary measures to stop it, and cease to be who we are. There are no other options.” By that latter point, he means that to undertake a successful defense of Europe from the tsunami of migration from the south would require mass killing, such that the Europeans would betray their humanitarianism.

From a 2013 interview with Raspail, in a French magazine (translation is mine, via Google):

How can Europe face these migrations?

There are only two solutions. Either we try to live with it and France – its culture, its civilization – will disappear even without a funeral. This is, in my opinion, what will happen. Or we don’t make room for them at all – that is to say, one stops regarding the Other as sacred, and we rediscover that your neighbor is primarily the one living next to you. This assumes that you stop caring so much about these “crazy Christian ideas”, as Chesterton said, about this erroneous sense of human rights, and that we take the measures of collective expulsion, and without appeal, to avoid the dissolution of the country in a general miscegenation [métissage, a word that in French carries more the sense of the English words “multiculturalism” and “diversity”]. I see no other solution. I have traveled in my youth. All peoples are exciting but when mixed enough is much more animosity that grows that sympathy. Miscegenation is never peaceful, it is a dangerous utopia. See South Africa!

At the point where we are, the steps we should take are necessarily very coercive. I do not believe and I do not see anyone who has the courage to take them. There should be balance in his soul, but is it ready? That said, I do not believe for a moment that immigration advocates are more charitable than me: there probably is not one who intends to receive at home one of those unfortunates. … All this is an emotional sham, an irresponsible maelstrom which will swallow us.

Raspail’s vision is extremely dark. But nobody has yet demonstrated to my satisfaction why he does not see the world of the near future as it really is, not as the rest of us prefer it to be. The fact that the choice he forces us to see is horrible doesn’t make it go away. Europe can’t avoid the choice. To refuse it is to choose. The coming migrants aren’t interested in the moral dilemmas of Europeans.

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.