Dante In Recovery

A reader writes to commend my current TAC cover story (not yet online), which tells the tale of how reading Dante’s Divine Comedy pulled me out of a deep hole. He says:

When I went to rehab I took a stack of books with me. As it happens, books are not allowed. They told me to turn them over at the check-in desk. I stacked them on the table when a passing therapist spotted the Commedia. “He should keep that one,” he said. “It’s the best book on recovery ever written.”

This is a good point on which to make a final general remark about Dante’s great work before we start on Wednesday talking about the Purgatorio, canto by canto. Aside from a work of profound spiritual depth and resonance, the Commedia is a story about a man who walked out of a trap of his own making — a journey that required him first to go through Hell. Dante scholar Harriet Rubin reflects on the Commedia as perhaps the world’s greatest self-help book. Excerpt:

For a terrifying moment, Dante see himself in Ulysses. Dante, too, revels in the art of persuasion. Is his own journey to Paradise another mad pursuit, his own cleverness a form of deception? Dante reasons that to Ulysses, virtue and knowledge were the same thing. But Dante concludes that they are not. To use superior wisdom in deceiving others is spiritual theft. Leaders must use skill and cleverness not for personal gain but to promote honor, to create a just state. Personal happiness is not possible in a divided state. And ambition without virtue is madness. This realization makes “Inferno 26” the turning point of “The Divine Comedy” and conveys how Dante’s entire masterpiece may be read at a deep level, one that Osip Mandelstam, a dissident writer in Stalin’s Russia, said works as a kind of literary medicine, curing those who read it of their self-created ills of ego and reckless opportunism. Mandelstam had such faith in the curative power of “The Divine Comedy” that he smuggled a copy into his prison cell.

In “Survival in Auschwitz,” Primo Levi writes of how “Inferno 26” gives him perspective on the world that produced the camps. In 1944, Jean, a junior guard in Auschwitz, assigns Levi the task of helping him carry the day’s watery soup from kitchen to barracks because Jean wants to learn Italian. Both men dream of a life beyond the barbed wire of the camps. For Levi, the job is a great reward, though the hundred-pound kettle could buckle the knees. For a few minutes a day he could walk in the sunshine. He chooses “Inferno 26” to teach Jean, but Levi’s memory falters when he gets to the line in which Ulysses tries to crash through a barrier, inspiring his men: “Consider your origin:/you were not made to live like brutes,/but to follow virtue and knowledge.” For Levi, as for Dante, the question is whether his voyage through hell would become a new beginning or an end.

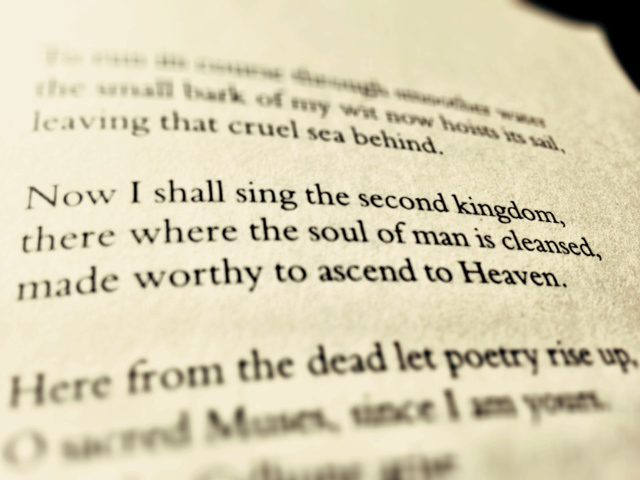

Purgatorio records the middle stage of that journey. Again, I feel the need to reassure non-Catholic readers: you do not have to believe in the Catholic doctrine of Purgatory to benefit greatly from this reading. If you take the addiction-and-recovery metaphor, Inferno is landing in rehab and facing all the things you did to wreck your life. Purgatorio is learning how to overcome the tendencies and weaknesses within yourself that caused you to do those destructive things. Paradiso is what life looks like when you have been healed.

This passage from Erich Auerbach’s study Dante: Poet Of The Secular World is important to understanding the essential character of the Divine Comedy:

Nothing is left open but the narrow cleft of earthly human history, the span of man’s life on earth, in which the great and dramatic decision must fall; or to look at it the other way round, from the standpoint of human life, this life, in all the diversity of its manifestations, is measured by its highest goal, where individuality achieves actual fulfillment and all society finds it s predestined and final resting place in the universal order. Thus, even though the Comedy describes the state of souls after death, its subject, in the last analysis, remains earthly life with its entire range and content; everything that happens below the earth or in the heavens above relates to the human drama in this world. But since the human world receives the measures by which it is to be molded and judged from the other world, it is neither a realm of dark necessity nor a peaceful land of God; no, the cleft is really open, the span of life is short, uncertain, and decisive for all eternity; it is the magnificent and terrible gift of potential freedom which creates the urgent, restless, human, and Christian-European atmosphere of the irretrievable, fleeting moment that must be taken advantage of; God’s grace is infinite, but so also is His justice and one does not negate the other. The hearer or reader enters into the narrative; in the great realm of fulfilled destiny he sees only himself alone unfulfilled, still acting up on the real, decisive state, illumined from above but still in the dark; he is in danger, the decision is near, and in the images of Dante’s pilgrimage that draw before him he sees himself damned, making atonement, or saved, but always himself, not extinguished, but eternal in his very own essence.

A core message of the Commedia: You must choose. And you cannot put it off forever.

How do we choose rightly? That is, how do we strengthen our vision to see the right choices, and our will to make them? How do we conquer ourselves? That is the topic of Purgatorio. We begin our Lenten climb up the mountain tomorrow.