Alas For Fortress Poland

Today was a very long day, and a rewarding one. I say “rewarding” in the sense that it is always better to know the painful truth than rest in a comforting lie. What happened today, on my first full day in Poland, was that I was slapped hard upside the head by conservative Catholics who told me that this idea Americans have that Poland is a bastion of traditional Christian resistance to liquid modernity is a fantasy that needs to die.

Let me repeat that: I was told this not by secular liberals, but by conservative young Catholics who are deeply concerned about the future of their country.

It’s late here in Warsaw, and I don’t have the time or the energy to listen to the recordings of the interviews I did today. Half of the things I learned were not through formal interviews, but from multiple conversations, in particular with Gen Z folks (college-age people). Caveat: this is only one day, and I expect that I will meet with Millennials, Gen Z-ers, and others who have different views. But I have to tell you, this was profoundly jarring.

I have some notes I took, but without listening to the recordings, I am mostly I am going from memory. I want to get this down now, while I’m thinking about it. What follows is raw. I’m going to write only what I heard today, with a minimum of analysis. I’m going to need to think hard about this. Let me say at the start that as difficult as some of this was to hear today, I am grateful that I heard it. It puts my book project into a certain perspective.

As regular readers know, I’m here in Poland in part to do interviews for my upcoming book. I’m talking to people who lived through Communism, trying to discern what lessons we can learn today for how to resist the soft totalitarianism that is arising today.

In happier news, I had a long, wonderful conversation today with Anna and Krzystof Antoni Zdanowski, both of whom married and raised children under Communism, though their two younger children were born as the Communist era was coming to an end. The Zdanowskis are luminous Catholics — gentle, kind, hospitable, and deeply pious. Krzystof was a member of Solidarity back in the day. I can’t say enough how much they impressed me, and how much it meant to me to hear their stories. Krzystof explained how for him, growing up under Communist rule, the Church meant everything. It was a source of wisdom, of solace, of knowing right from wrong, of standing up for the Truth, and a “safe place” — meaning a haven from the empire of lies. Their testimony was deeply moving. I got from them exactly what I hope to gain from these interviews. It reminded me of the interviews I’ve done in Slovakia and the Czech Republic with members of the anti-communist resistance.

Toward the end of our discussion, their 31-year-old son, also named Krzystof, dropped by their home. We talked for a bit. He too is a devout Catholic, and runs his own tech firm. He was born two years before Communism ended in Poland. He told me he did not feel that it affected his life at all. He was raised in a free country. He speaks excellent English, in part because he does so much business in North America. I started to put some of the questions to him that I had put to his parents, and he couldn’t really answer them. As he explained in our short conversation, he has no memory of Communism, and he’s not interested in politics. For some reason, I had not reckoned with how unmarked by even the residue of Communism that the post-Communist generation would be.

As we walked back to the train, my interpreter — who I’ll call Maciej — told me that this is totally normal. He is 22, and a student. He is so young that he doesn’t have much memory even of John Paul II. Maciej explained to me that for the Millennials (Krzystof Jr.’s generation) and Generation Z (his generation), Communism is an abstraction. A lot of younger Poles simply don’t listen to their parents and grandparents talking about it, he said, because they can’t relate to it out of their own experience, but also because they have come to think of “Communism” as the thing many in the older generations talk about to avoid having to come to terms with challenges in the world today.

As he spoke, I thought about how US conservatives of a certain age talk a lot about Ronald Reagan that way, and how peculiar that sounds to younger people with no memory of him, or the times that produced him. Some older Catholics are that way about John Paul II.

It was a long day, as I said, and I had a number of conversations with the young. I’m not going to name any of them here, because I wasn’t doing formal interviews. I’m going to find out how to get in touch with them and see if I can quote them later, in the book, if appropriate. For this blog post, though, I’m going to condense the gist of the conversations. Whenever I quote something below, rest assured it’s an actual quote.

I was knocked flat by the anger at the Catholic Church — from the devout! I heard the same anger in Warsaw today that I heard from Gen Z Catholics in Spain earlier this year. If I were the Polish bishops, I would be very, very worried. One young man said:

“Under Communism, the State was against the Church, but Polish society was on the Church’s side. In the future, both will be hostile to the Church. Under Communism, the Church was a nice place to be. Everyone who opposed Communism found a place in the Church. Today, not attending Church is seen as an act of resistance.”

Resistance against what? I asked. The answers: the hypocrisy and self-satisfaction of the bishops, and the feeling that the political class has abandoned their generation. “We all say that in ten years, Poland will be a second Ireland,” said one person.

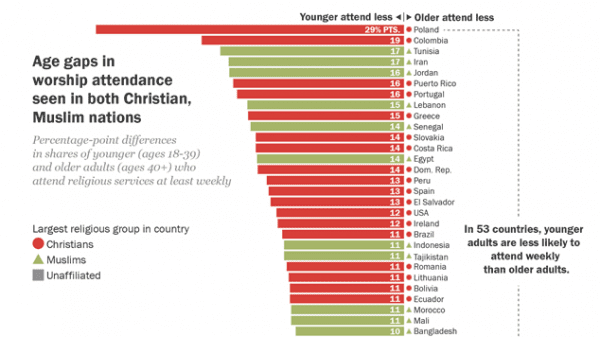

Someone pointed me to this Pew survey from last year showing that of 46 countries where more of the young (18 to 39) say that religion is not important to them than older people who say the same, Poland leads the pack. There is a 23 percent gap between the young who say religion is not very important to them, and the old who say the same thing. And look at this:

The numbers are about the same in terms of the “daily prayer gap,” meaning many more young Poles do not pray daily than do older Poles. Last year, Sunday mass attendance dipped below 40 percent in Poland for the first time. My interlocutors today told me that that number will continue declining as the old pass away.

The sex abuse scandal finally arrived in Poland, and it’s rocking the church here. The Polish clerical sex abuse documentary movie Tell No One — which you can watch for free, subtitled, on YouTube — has been viewed over 22 million times. One of the Gen Z guys today told me how enraged he and his friends were to see that the disgraced Archbishop Juliusz Paetz, a sex abuser of seminarians who was forced to resign in 2002, was present last October at the Vatican for the canonization of Paul VI. Paetz had been forbidden at the time to present himself in public as a bishop, but he repeatedly defied that Vatican order. In 2016, the Vatican reminded Paetz forcefully that he should not appear in public. But last October, according to my informant, Poles watching the mass from Rome on television saw the Archbishop there in full dress. Said this man, angrily, “My friends and I could hardly believe our eyes.”

My young sources said that the bishops are completely out of touch with society. Even the conservative ones, many of them are living in the past. They still believe that they have authority in Poland, that people will follow them because they are the bishop, and that’s how Poland has always been. A faithful Catholic: “They have no understanding of their real position in our society today.”

Another quote, from a conservative Gen Z Catholic:

“The main problem with my generation is apathy. Most of them don’t even care about the Church enough to hate it. If some people say this isn’t true, or that this is not going to matter in the long run, they are blind. You will hear that from a lot of older people, but they don’t see what’s happening.”

(For the record, I didn’t hear that from the Zdanowskis, who seemed to me to be quite concerned about the future of the faith in Poland. But this was only one couple.)

There was more, including the prediction that faith is going to decline also because the Polish family is falling apart (“That’s in line with Mary Eberstadt’s theory of secularization,” I said.) Talking about politics with these young conservatives, I heard anger and frustration at the ruling Law and Justice Party, but also fear of what the left-wing parties will do to the Church and to causes that social conservatives care about.

I did not expect to hear most of this today. To be honest, I did not expect to hear any of it in Poland. Maciej told me today that he expects to “be buried by a man with a shovel” — as opposed to a priest. “What do you mean?” I asked him. “You think there won’t be any priests around to bury you?”

“Yes, that’s exactly what I mean,” he said.

Talking with these young Catholics today will change the way I do the rest of the interviews. Like I said, I’m glad I came to Poland. I would never have guessed that these fault lines ran so deep, and so hot, in Polish society — even among believing Catholics! There really is no safe place.

If you’re a Pole who disagrees with any of this I heard today, please let me hear from you. Cheer me up.

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.