Difficult Subjects

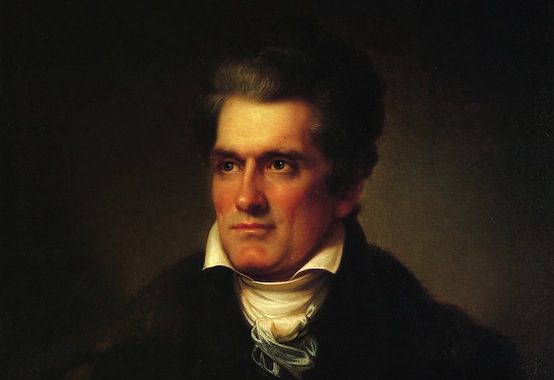

Are some people too morally monstrous to be the subject of a biography? Allen C. Guelzo reviews a new life of John. C. Calhoun. Without “biographies of difficult subjects,” he writes, “it might not be possible to write biographies at all”:

There are some biographies which are almost impossible to write. Sometimes this is because the subject is guilty of such monstrosities that the empathy required to write a worthwhile biography can undermine the moral judgment a difficult subject demands. Ian Kershaw, at the beginning of his two-volume biography of Adolf Hitler, admitted that ‘any biographical approach’ to a character like the Nazi fiend has the ‘inbuilt danger’ of requiring ‘a level of empathy with the subject which can easily slide over into sympathy, perhaps even hidden or partial admiration.’ Any attempts to understand Hitler as something other than a consummate devil—as an opportunist, a hypnotizer, an anti-Bolshevik, a social revolutionary, or a Weberian charismatic—all have lurking within them the ‘potential for a possible rehabilitation of Hitler’ as some version of a national hero, if only his ‘crimes against humanity’ could be somehow contextualized.

Yet, context is as much a necessity in biography as judgment; the one, in fact, has no meaning without the other. ‘The biographer’s mission,’ wrote Paul Murray Kendall, ‘is to perpetuate a man as he was in the days he lived—a spring task of bringing to life again, constantly threatened by unseasonable freezes.’ But context is itself a slippery task, and contextualizing a difficult subject sets up a different hazard for the biographer, that of being misunderstood as a co-conspirator in the subject’s project, so that both the subject and the biographer are heaped with opprobrium by a drone of self-congratulatory criticism.

For such a task, the great literary critic John Gardner laid down this rule: No true compassion without will, no true will without compassion. Without the will to judge, as Kershaw recognized, any empathy is suspect, and will be regarded that way. Without compassion, however—without a deep understanding of motives, times, places, losses, sorrows: context, again—the result will never rise above sanctimonious caricature.

In other news: Pompeii’s newly renovated Antiquarium opens fully for the first time in 40 years: “The museum was first established around 1873 by the archaeologist Giuseppe Fiorelli and was enlarged in the 1920s, before being partially destroyed in bombing during the Second World War. It closed down again in 1980 after the devastating Irpinia earthquake.”

The miraculous Mozart: “The story of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart begins with the ‘miracle of January 24, 1761.’ This is Jan Swafford’s apt phrase, found in his new biography, Mozart: The Reign of Love, for what happened one night in Salzburg when a four-year-old boy sat down at the harpsichord in his parents’ house and began to play. His sister Nannerl, age nine, had been practicing a scherzo, and he was taken with its lively rhythms. When she finished, he wanted to give it a try. Their father, Leopold, a composer, violinist, and music pedagogue, was astounded by what happened next: the boy immediately caught the gist of the piece. Within half an hour, despite being unable to read music and having had no previous harpsichord instruction, he had learned it by heart.”

Emmanuel Carrère’s confessional ethics: “In 1993, frustrated and unfulfilled, Emmanuel Carrère was waiting on two replies – one from Satan, the other from God. He was 35, with four novels behind him but not enough fame for his liking. On 9 January, a newspaper story offered hope: in a small town in the east of France, a man called Jean-Claude Romand had murdered his wife and children, and then his parents and their dog. Romand was modest, well-liked, wealthy and honest – or so it had seemed. Investigators soon learned that he had been living a lie, pretending to be a prestigious researcher at the World Health Organisation while embezzling money from friends and family. Finally, fearing exposure, he killed his whole family. Carrère sent a letter to Romand in prison: he wanted to understand, not judge, he said. It was two years before Romand replied, but the seeds of The Adversary (2000) were sown. God was a different matter. A few years earlier, Carrère had converted to Catholicism with manic zeal. He went to Mass daily, filled 18 notebooks with spiritual reflections and saw the face of the Lord in the leaves of a tree. He took communion and confessed his sins. Then, in April 1993, he stumbled on another story, about a young boy who had lost all his senses; he was lifeless but still alive. At the thought of such futile suffering, Carrère’s faith folded. ‘I forsake you, Lord, please do not forsake me,’ he wrote on Easter Sunday. Unlike Romand, God never got back to him. That didn’t prevent Carrère imagining their correspondence in The Kingdom, his longest book, published in 2014. In The Kingdom, Carrère admits to ‘obsessively thinking … that whatever happens to me, sooner or later, will come out in book form’. So far, with some exceptions, he has been generous, rarely writing for revenge, indeed frequently turning on himself. Since The Adversary, all of his books have been non-fiction accounts written in the first person. ‘Not out of narcissism,’ he insists (though there is plenty of that too), ‘but honesty.’ Whatever Carrère’s motives, his early prayers for success were answered. With Romand as his subject, he found a style and an audience. The Adversary was translated into 23 languages and made into a movie. ‘Today, we are the two most important writers in France,’ Michel Houellebecq told Carrère in late 2018. For Houellebecq, putting another writer on the same plane as himself was a rare display of modesty, but the fact of Carrère’s two decades of critical and commercial success cannot be denied.”

Parul Sehgal reviews Lauren Oyler’s Fake Accounts.

Literary agency fires employee for using Parler and Gab: “The agency’s founder, Jennifer De Chiara, announced the decision in a series of tweets on Monday that were later listed as ‘protected’ and inaccessible to anyone but De Chiara’s followers. The tweets were reported by Newsweek. ‘The Jennifer De Chiara Literary Agency was distressed to discover this morning, January 25th, that one of our agents has been using the social media platforms Gab and Parler. We do not condone this activity, and we apologize to anyone who has been affected or offended by this,’ De Chiara wrote.”

Cathleen Kaveny remembers Vatican Latinist Reginald Foster: “Reginald Foster, OCD, the celebrated Latinist who died in December, committed one act of civil disobedience in the course of his duties for the Vatican. Tasked with making the official Latin version of a text written in Italian or Polish by Pope John Paul II, Reggie came across a phrase referring to Latin as a ‘dead’ language. He just couldn’t bring himself to translate that. So he successfully proposed substituting the adjective ‘ancient’ instead. To conscript Latin to confirm its own demise was existentially unacceptable to Reggie. His life’s work was communicating the language’s vitality to generations of students.”

Rare violin tests Germany’s looting restitution system: “No one knows why Felix Hildesheimer, a Jewish dealer in music supplies, purchased a precious violin built by the Cremonese master Giuseppe Guarneri at a shop in Stuttgart, Germany, in January 1938. His own store had lost its non-Jewish customers because of Nazi boycotts, and his two daughters fled the country shortly afterward. His grandsons say it’s possible that Hildesheimer was hoping he could sell the violin in Australia, where he and his wife, Helene, planned to build a new life with their younger daughter. But the couple’s efforts to get an Australian visa failed and Hildesheimer killed himself in August 1939. More than 80 years later, his 300-year-old violin — valued at around $185,000 — is at the center of a dispute that is threatening to undermine Germany’s commitment to return objects looted by the Nazis.”

Photo: Pluto’s icy landscape

Receive Prufrock in your inbox every weekday morning. Subscribe here.

Comments