The Joy Of Resisting Conformity

When I was at LSU as an undergraduate in the 1980s, a high school friend who attended an Ivy League school took a semester of classes at LSU so he could go on the year abroad program that LSU and his Ivy school were part of, without having to pay Ivy tuition. He told me once that it was such a relief to be at a campus where everything wasn’t politicized. This surprised me, because my friend was quite lefty, and LSU in the 1980s was … not. He explained that you couldn’t do a damn thing at his school without people imputing political motive to it.

“If I take the stairs instead of the elevator, somebody is going to congratulate me on making an environmentalist statement,” he said. That kind of thing. It was exhausting, all the drama.

We lost touch over the years. I just looked him up. He has become an astonishingly accomplished scholar in his (non-political!) field, but now teaches at a super-woke university. I wonder what he thinks of it all. I remember him as a very gentle soul. He probably lets it all roll off his back as best he can, and gets on with his work. I looked at his publication record, and it’s very impressive. Fortunately he works in a field that hasn’t yet been woke-ified. The totalitarians will eventually get there.

During my undergraduate years, I was really interested in ideas, but I didn’t have a scholarly temperament. Fortunately I discovered journalism back then, and realized I would be happier writing about ideas as a journalist than as an academic. Thank God for that. I mean that literally: I thank Him for delivering me from the fate of a conservative, or even independent-minded, academic. If I were stuck in the academy now, given what it has become, and had no way to exit it, I would probably be crushingly depressed.

I was in New Orleans to be filmed for a documentary on American decline. It was a long interview, and at one point I began to talk about the difference between campus life when I was an undergraduate, and campus life today. I hope I’m not seeing it through the lenses of poetic memory, but I recall that we were all so happy to be away from our parents’ home, trying out adulthood. We made stupid mistakes — I got popped for drunk driving the first semester of my freshman year, and got to spend the night in the downtown jail; the booze culture at LSU in my day was really destructive — but this was all part of learning what it meant to be an adult. Back then, it was possible to have conversations with people who disagreed with you politically. They weren’t easy conversations, but there was a generally shared understanding that being at college was where you learned how to deal with people unlike yourself, in a constructive way.

Those were the days! Today in Bari Weiss’s invaluable Substack, the essayist William Deresiewicz, who taught English at Yale for a decade, reflects on how today’s students, at least the ones at elite colleges, are a flock of sheep who don’t know how to think independently, but rather know how to hack the American meritocracy, which is really a “baizuocracy” — a terms I invented using the Chinese insult for doe-eyed Western leftists. Excerpt:

I was involved in the anti-apartheid protests at Columbia in 1985. Already, by then, the actions had an edge of unreality, of play, as if the situation were surrounded by quotation marks. It was, in other words, a kind of reenactment. Student protest had achieved the status of convention, something that you understood you were supposed to do, on your way to the things that you’d already planned to do, like going to Wall Street. It was clear that no adverse consequences would be suffered for defying the administration, nor were any genuinely risked. Instead of occupying Hamilton Hall, the main college classroom building, as students had in 1968, we blocked the front door. Students were able to get to their classes the back way, and most of them did (including me and, I would venture to say, most of those who joined the protests). “We’ll get B’s!” our charismatic leader reassured us, and himself—meaning, don’t worry, we’ll wrap this up in time for finals (which is exactly what happened). The first time as tragedy, the second time as farce.

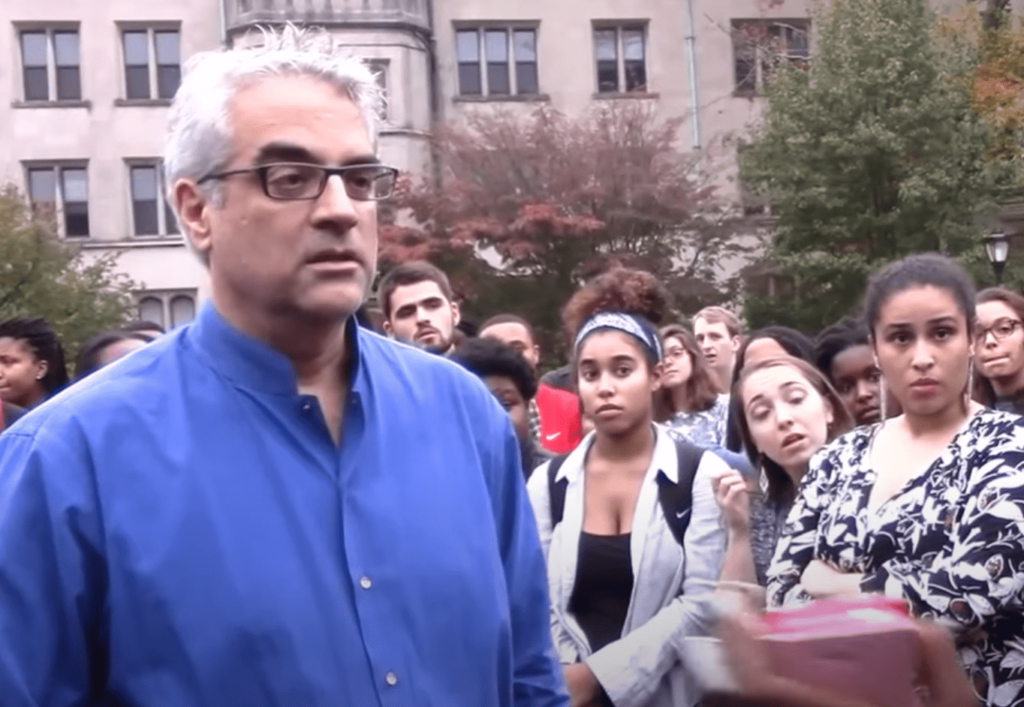

And so it’s been since then: the third, fourth, tenth, fiftieth time. In a recent column, Freddie deBoer remarked, in a different context, that for the young progressive elite, “raised in comfortable and affluent homes by helicopter parents,” “[t]here was always some authority they could demand justice from.” That is the precise form that campus protests have taken in the age of woke: appeals to authority, not defiance of it. Today’s elite college students still regard themselves as children, and are still treated as such. The most infamous moment to emerge from the Christakis incident, captured on a video the world would later see, exemplifies this perfectly. Christakis’s job as the head of a residential college, a young woman (one could more justly say, a girl) shriek-cried at him, “is not about creating an intellectual space! It is not! Do you understand that? It’s about creating a home!”

We are back to in loco parentis, in fact if not in law. College is now regarded as the last stage of childhood, not the first of adulthood. But one of the pitfalls of regarding college as the last stage of childhood is that if you do so then it very well might not be. The nature of woke protests, the absence of Covid and other protests, the whole phenomenon of excellent sheephood: all of them speak to the central dilemma of contemporary youth, which is that society has not given them any way to grow up—not financially, not psychologically, not morally.

The problem, at least with respect to the last two, stems from the nature of the authority, parental as well as institutional, that the young are now facing. It is an authority that does not believe in authority, that does not believe in itself. That wants to be liked, that wants to be your friend, that wants to be thought of as cool. That will never draw a line, that will always ultimately yield.

Children can’t be children if adults are not adults, but children also can’t become adults. They need something solid: to lean on when they’re young, to define themselves against as they grow older. Children become adults—autonomous individuals—by separating from their parents: by rebelling, by rejecting, by, at the very least, asserting. But how do you rebel against parents who regard themselves as rebels? How do you reject them when they accept your rejection, understand it, sympathize with it, join it?

The 1960s broke authority, and it has never been repaired. It discredited adulthood, and adulthood has never recovered. The attributes of adulthood—responsibility, maturity, self-sacrifice, self-control—are no longer valued, and frequently no longer modeled. So children are stuck: they want to be adults, but they don’t know how. They want to be adults, but it’s easier to remain children. Like children, they can only play at being adults.

You might recall a story I like to tell about a European friend who spent a year recently at Harvard, doing graduate study as part of a program. He told me the thing that stood out the most for him about that year was how “fragile” (his word) elite American students are. He spoke about how professors would modify their classroom presentations to accommodate the fragility of students, who would ask him not to talk about this or that idea, because it would trigger their anxieties.

My friend went on to say that these students all believed fully that they had a destiny to rule the world. They had an unshakable belief in the justice of their own privilege. But they also crumpled before ideas that challenged them.

These people are protected by real institutional power. But they are soft, and as they move into leadership positions, they will not be able to hold their ground in the face of a determined and intelligent opposition. Now is the time to create that opposition, and to network it. This is the fight of our present, and our future. These people are Creampuff Stalins. They think like totalitarians, but they are too anxious to sustain a prolonged and intelligent assault. They hold institutional power and resources, but they lack true grit. Over the weekend I talked to a Ukrainian immigrant friend, who told me about how just about everybody he knows back home is in the fight against the Russians. Even his 61-year-old brother-in-law returned to Ukraine from his safe job in Poland, to fight the invaders. Listening to him, I realized the same lesson that the US ought to have learned in Vietnam and Afghanistan: you can throw immense material resources at a people you intend to conquer, but if they are fighting for their homeland, they are hard to defeat.

Admittedly this is only of limited application to the kind of culture war fight I’m talking about here. In what sense are elite institutions our “homeland”? It’s hard to see. Nothing will change until ordinary people come to understand that the insane ideas and policies inculcated into elite students at these universities will ultimately affect them, as the ideas and practices trickle down through the institutions that they deal with daily. It’s instructive to consider that the fights against wokeness finally gained traction when people came to understand that these activists were trying to poison the minds of their children — and they took political action. What the movement against CRT in schools in northern Virginia did — that’s the way. Ron DeSantis — he’s the way. One of the reasons I tout Viktor Orban is that, for example, he used political power to defund and disaccredit the bullsh*t academic field of “gender studies” in state-funded Hungarian universities. He didn’t apologize for it, and didn’t give a rat’s rear end what the bien-pensants of the Left had to say about it. He doesn’t want this garbage taking root in his country, if he can help it, and convincing Hungarian adolescents to cut off their balls and breasts.

Are we serious about fighting the culture war? If so, it’s going to require developing contempt for these elite institutions that already hold contempt for us — and making them pay real prices. They are going to hoot and holler about our “illiberalism” — while remaining perfectly blind to their own left-wing illiberalism, and completely sanguine about the justice of their own privilege. Deresewiecz writes:

But wokeness also serves a deeper psychic purpose. Excellent sheephood is inherently competitive. Its purpose is to vault you into the ranks of society’s winners, to make sure that you end up with more stuff—more wealth, status, power, access, comfort, freedom—than most other people. This is not a pretty project, when you look it in the face. Wokeness functions as an alibi, a moral fig leaf. If you can tell yourself that you are really doing it to “make the world a better place” (the ubiquitous campus cliché), then the whole thing goes down a lot easier.

All this helps explain the conspicuous absence of protest against what seem like obviously outrageous facts of life on campus these days: the continuing increases to already stratospheric tuition, the insulting wages paid to adjunct professors, universities’ investment in China (possibly the most problematic country on earth), the draconian restrictions implemented during the pandemic.

Wendell Berry, a man of the ornery and anti-woke Left, once sarcastically wrote:

Quit talking bad about women, homosexuals, and preferred social minorities, and you can say anything you want about people who haven’t been to college, manual workers, country people, peasants, religious people, unmodern people, old people, and so on.

That’s taken from his great essay “The Joy Of Sales Resistance”. He goes on — again, in a sarcastic vein:

The first duty of writers who wish to be of any use even to themselves is to resist the language, the ideas, and the categories of this ubiquitous sales talk, no matter from whose mouth it issues. But, then, this is also the first duty of everybody else. Nobody who is awake accepts the favors of these hawkers of guaranteed satisfactions, these escape artists, these institutional and commercial fanatics, whether politically correct or politically incorrect. Nobody who understands the history of justice or of the imagination (largely the same history) wants to be treated as a member of a category.

I am more and more impressed by the generality of the assumption that human lives are properly to be invented by an academic-corporate-governmental elite and then either sold to their passive and choiceless recipients or doled out to them in the manner of welfare payments. Any necessary thinking—so the assumption goes—will be done by certified smart people in offices, laboratories, boardrooms, and other high places and then will be handed down to supposedly unsmart people in low places—who will also be expected to do whatever actual work cannot be done cheaper by machines.

Such a society, whose members are expected to think and do and provide nothing for themselves, will necessarily give a high place to salesmanship. For such a society cannot help but encourage the growth of a kind of priesthood of men and women who know exactly what you need and who just happen to have it for you, attractively packaged and at a price no competitor can beat. If you wish to be among the beautiful, then you must buy the right fashions (there are no cheap fashions) and the right automobile (not cheap either). If you want to be counted as one of the intelligent, then you must shop for the right education (not cheap but also not difficult).

Actually, as we know, the new commercial education is fun for everybody. All you have to do in order to have or to provide such an education is to pay your money (in advance) and master a few simple truths:

- Educated people are more valuable than other people because education is a value-adding industry.

- Educated people are better than other people because education improves people and makes them good.

- The purpose of education is to make people able to earn more and more money.

- The place where education is to be used is called “your career.”

- Anything that cannot be weighed, measured, or counted does not exist.

- The so-called humanities probably do not exist. But if they do, they are useless. But whether they exist or not or are useful or not, they can sometimes be made to support a career.

- Literacy does not involve knowing the meanings of words, or learning grammar, or reading books.

- The sign of exceptionally smart people is that they speak a language that is intelligible only to other people in their “field” or only to themselves. This is very impressive and is known as “professionalism.”

- The smartest and most educated people are the scientists, for they have already found solutions to all our problems and will soon find solutions to all the problems resulting from their solutions to all the problems we used to have.

- The mark of a good teacher is that he or she spends most of his or her time doing research and writes many books and articles.

- The mark of a good researcher is the same as that of a good teacher.

- A great university has many computers, a lot of government and corporation research contracts, a winning team, and more administrators than teachers.

- Computers make people even better and smarter than they were made by previous thingamabobs Or if some people prove incorrigibly wicked or stupid or both, computers will at least speed them up.

- The main thing is, don’t let education get in the way of being nice to children. Children are our Future. Spend plenty of money on them but don’t stay home with them and get in their way. Don’t give them work to do; they are smart and can think up things to do on their own. Don’t teach them any of that awful, stultifying, repressive, old-fashioned morality. Provide plenty of TV, microwave dinners, day care, computers, computer games, cars. For all this, they will love and respect us and be glad to grow up and pay our debts.

- A good school is a big school.

- Disarm the children before you let them in.

Of course, education is for the Future, and the Future is one of our better-packaged items and attracts many buyers. (The past, on the other hand, is hard to sell; it is, after all, past.) The Future is where we’ll all be fulfilled, happy, healthy, and perhaps will live and consume forever. It may have some bad things in it, like storms or floods or earthquakes or plagues or volcanic eruptions or stray meteors, but soon we will learn to predict and prevent such things before they happen. In the Future, many scientists will be employed in figuring out how to prevent the unpredictable consequences of the remaining unpreventable bad things. There will always be work for scientists.

We need to learn the joy of resisting Princeton, and Yale, and Harvard, and McKinsey, and Netflix, and Disney, and The New York Times, and NPR, and the Pentagon, and the Human Resources Department, and the public school that has reinvented itself as a woke madrassah. And that resistance has to be more than just a matter of arranging our thoughts and emotions. These conformists are going to use whatever institutional power they have against people like us — unless we make them pay serious prices.

What kind of prices? Let us ponder. We are in a culture war whether we want to be or not. The fight that matters is not going to be led by right-wing grifters who simply profit off of stoking angry emotions. The fight that matters is the one led by serious thinkers and politicians who want to see change in the world, not change in their pockets.