When Censorship Moves Way Beyond Alex Jones

Donald Trump is preparing to unleash the Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission as antitrust warriors against the tech giants. And good on him. Breaking up the monopolies on speech might save us—particularly anyone right-of-center—from encroaching online deplatforming, and preserve our ability to hear ideas outside echo chambers of bullied consensus.

The First Amendment doesn’t restrain censorship by private social media companies. Thus have progressives today reveled in their newfound power to enforce their own opinions through deplatforming. That only works because the platforms matter as near-monopolies; no one cares who gets kicked off MySpace. If you end the monopolies, you defang deplatforming.

For much of American history, the media published things—on paper, then on radio, movies, TV, art shows, the Internet, and so on—and the First Amendment protected them. That covered both nice thoughts you and your grandma agreed with and vile thoughts from ideologies your grandpa fought against. As in “I disagree with what you say, but will fight for your right to defend it.”

Then social media hit some kind of cultural saturation point around the 2016 election. People couldn’t produce and consume enough opinion, and even traditional media dumped old-timey reporting in favor of doing stories based on what others posted online. It was a mighty climax for the Great Experiment in Free Speech—no filters, no barriers, a global audience up for grabs. Say something interesting and you went viral, your thoughts forever alongside Edward R. Murrow’s, Rachael Maddow’s, and the candidate herself.

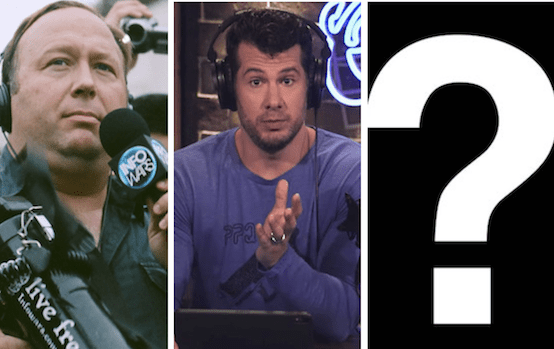

Then, with the election of Donald Trump and backlash against his speech, some began not just to tolerate but to demand censorship. First they came for Russian media outlets RT and Sputnik, and few shed a tear. Free speech had become weaponized, critics opined, complaining that it just wasn’t right that platforms like YouTube could put Alex Jones’s thoughts alongside those of “established” journalists. When Twitter initially dragged its feet in banning Jones, a “journalist” from CNN helpfully dug through Jones’s tweets to find examples of where he’d broken the rules.

Jones (and soon Milo Yiannopoulos, Richard Spencer, Ann Coulter, et al) had few friends outside his own supporters, so it was easy to condone his deplatforming. But that was only round one. Progressives next discovered that these deplatformed voices were just the tip of a white supremacist iceberg, a legion of hate seeking to stomp out immigrants, people of color, the 50 percent of the population who are women, all shades of LGBT, and perhaps democracy itself. And what was fueling this dirty fire of intolerance, allowing these men to organize (what the Bill of Rights calls “freedom of assembly” the deplatforming community calls “coordinative power”), raise money, and spread their bile (deplatformers call it red pilling)? Social media. Someone needed to do something about all this free speech before it was too late and America elected the wrong president again.

Progressives realized that people who thought like them controlled key platforms in America. Twitter could silence what once were inalienable rights. The sparse haiku clarity of the First Amendment was replaced with groaning terms of service that meant whatever the mob wanted them to mean. The freedom to speak on social media no longer existed independent of the content of speech. And thus the once loathed Heckler’s Veto, the shout-down, was reimagined as the righteousness of deplatforming, the online equivalent of actually punching Nazis to silence them.

So there was nothing to prevent the deplatforming of journalist Steven Crowder for calling Vox writer Carlos Maza a “lispy queer Latin” on YouTube. In fact, Maza successfully campaigned across social media to get YouTube to demonetize Crowder when the site initially hesitated. YouTube then announced an update to its hate speech policy broadly prohibiting “videos alleging a group is superior in order to justify discrimination, segregation or exclusion,” and deleted the classic documentary studied in every film school, Leni Riefenstahl’s 1935 Triumph of the Will. YouTube has also deplatformed history teachers for uploading archive material related to Adolf Hitler, saying they breached the new guidelines banning hate speech.

The site had already sent entire genres down the Memory Hole, banning “videos promoting or glorifying racism and discrimination.” That purge deplatformed News2Share, a site that covered everything from pro-Julian Assange protests to Second Amendment supporters rumbling with Antifa. YouTube proudly asserts that since 2017, it has reduced the views of “supremacist” videos by 80 percent.

Gab, a sort of alternative Twitter, was threatened by Microsoft with the cancelation of its web domain because of two “offensive” posts made by a minor Republican candidate. Facebook/Instagram banned “white nationalist and separatist” content, including at one point documentaries from Prager University. It also deleted posts from veteran journalist Tim Shorrock criticizing the New York Times‘ coverup of American support for previous South Korean dictatorships.

Google refused ads for a gala featuring Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, something they claimed was in violation of their policy on “race and ethnicity in personalized advertising.” Google the company sees itself at the nexus of an ideological war, declaring, “Although people have long been racist, sexist, and hateful in many other ways, they weren’t empowered by the Internet to recklessly express their views with abandon.”

On another site, parents who started a petition questioning their local school’s transgender policy were deplatformed. I was deplatformed by Twitter. There are many more examples. Mashable claimed that 2018 was the year “we cleaned up the Internet,” while Vice announced that deplatforming “works” and celebrated the censorship of its fellow journalists.

Two visions of free speech have now taken hold in America. One is widely dismissed as dangerous because it fights for a marketplace of ideas that could include hate speech, while another dances a jig because America’s new censors are ideologically sympathetic corporations currently supporting the progressive agenda. The latter group is comprised of people seemingly unable to project a future where those corporate censors might support a different set of views. Instead, as a mob, they gleefully point to “hate speech” and let @jack purify away.

What to do? Efforts to extend the First Amendment to entities like Facebook, arguing that they are the new public squares (seven of 10 American adults use a social media site), have been unsuccessful.

Trying to classify social media companies as “publishers” has also been unsuccessful because they insist that they are “platforms.” They say they are like the phone company, which lets you talk to a friend but exercises zero control over what you say.

Being a platform is desirable for Facebook and the others, as it allows them to have no responsibility for the content they print, no need to create transparent rules or appeals processes for deplatforming, and users have no legal recourse. Publishers, on the other hand, are responsible for what they print, and can be taken to court if it’s libelous or maliciously false.

Social media’s claim to be a platform and not a publisher is based on Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act. That section, however, was predicated on social media companies being neutral public forums in return for legal protections against being sued over content they present. Now Twitter wants it both ways—they want the protection of being a platform but the power to ideologically manipulate their content as publishers do.

Breaking through the platform-publisher question will require years of court battles. The growth of much of the web has been driven by the lack of responsibility for the content third parties chuck online. It is a complex situation that applies to everything from knitting site hosts to Nazi forums, and across international borders.

Yet social media entities’ control over speech is so significant that a more immediate solution is demanded. Google owns 90 percent of the search market, three quarters of mobile browsing and 70 percent of desktop, and, along with Facebook, 50 percent of online ads. YouTube dominates video. Facebook makes up two thirds of all social media, with Twitter holding down most of the rest. Large enough on their own, the platforms also work in concert. One bans, say, Alex Jones, and most of the others follow. And then whomever is last is chided into action by the mob and threatened with advertiser boycotts. Eventually, even Venmo and Paypal cut Jones off.

With legal and legislative solutions ineffectual for preserving free speech online, enter the major antitrust enforcement agencies of the executive branch. The Department of Justice is preparing to investigate Google’s parent company, Alphabet, while the Federal Trade Commission is doing the same for Facebook. The goal may be to break the tech giants into multiple smaller companies, as was done at the dawn of mass electronic communication in America.

The end of social media mega-companies, with none big enough to effectively silence any significant amount of speech, would be a clumsy fix for a problem the Founders never imagined—citizens demanding corporate censorship because they don’t like the results of an election. It is nowhere near the comprehensive solution of an expanded First Amendment that a democracy should grant itself. But in a world where progressives fail to understand the value of free speech, it may provide enough of a dike to hold back the waters until reason again takes hold.

Peter Van Buren, a 24-year State Department veteran, is the author of We Meant Well: How I Helped Lose the Battle for the Hearts and Minds of the Iraqi People and Ghosts of Tom Joad: A Story of the 99%.

Comments