Getting Nixon Right

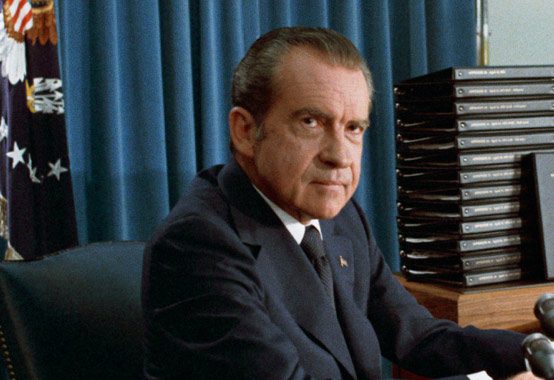

Un homme serieux. The phrase, found in a Newsweek column written by Joseph Alsop after Richard Nixon’s second inauguration, recurs frequently in Thomas Mallon’s engaging new historical novel, Watergate. Alsop believed that Nixon was un homme serieux in at least three senses:

The literal meaning is, of course, ‘serious man.’ Less literally, but more accurately, it means a man who has to be taken seriously. Less literally still, but more accurately in terms of the President’s thinking, it means a tough man, a hard man, a man not to be pushed around.

Each of these shades of meaning was intensely present in Nixon. He was a man of high intellect, an accomplished statesman—also something of, well, a crook.

What accounts for this whiplash-inducing quality of Nixon’s—this ability to mingle high purpose with common thuggery?

“He was the first American political figure I was really interested in. He just loomed over my whole life,” says Mallon, 60, via phone from Davidson College, where the former literary editor of GQ is a visiting professor. “I remember election night 1960 very well. I remember being very crestfallen when Nixon lost, and following his fortunes in the years that followed. Then he was president while I was in college for the whole time I was there—a tumultuous, tumultuous time.”

The Glen Cove, N.Y.-born Mallon, who among his many projects directs the creative writing program at George Washington University, is one of the vanishingly few conservatives who move in elite literary circles. (Mark Helprin is another.) He lives in Washington, D.C., and has made hay of its evolving company-town milieux before. Two Moons, for instance, takes place in the Gilded Age, while Fellow Travelers mines the McCarthy era and its lesser-known “lavender scare” baiting of homosexuals.

The novelist’s politics are in part an inheritance—his father was a New Dealer who anticipated Ronald Reagan’s rightward migration. “I was passionately for Goldwater in ’64, when I was turning 13,” he says. “And the libertarian aspect of his politics remains a strong streak in mine.” Nine years spent marinating in the Ivy League led to a period of leftism, but “the Carter presidency mostly cured me of that.”

As for today’s notional home for conservatives, Mallon says he’d like to see a GOP that’s “intellectually vigorous” and “de-clericalized.” “President Obama recently exaggerated when he said that today’s Republican Party would not nominate Ronald Reagan,” he says. “But if he’d said that about Goldwater, it would be true. Goldwater was anti-Falwell and pro-choice and pro-gay-rights, and would thus be unacceptable by today’s standards.”

But what about Nixon?

Mallon wasn’t even sure he wanted to include the already well-flogged Tricky Dick as a prominent character in Watergate, a fictional rendering of the infamous burglary—an attempt, the author surmises, to tie Sen. George McGovern’s campaign to Castro—and its aftermath. “Most of the historical fiction I’ve written has operated with minor characters rather than major players,” he says. In Henry and Clara (1995), for instance, Mallon chose to spotlight a couple who were seated in the Ford’s Theater box where Abraham Lincoln was shot, rather than Lincoln himself. “The traces of their lives were fairly scant. I hungered for new discoveries about them.”

“But this,” Mallon says, his voice trailing off for a moment, as if feeling anew the ache of exhaustion to which every amateur Watergate sleuth can attest.

“This is one of the few subjects I’ve written fiction about where I wound up wishing that there had actually been less material to look at. There are shelves and shelves of memoirs. Everybody wrote a memoir—if only to pay his legal bills. There’s all the Ervin Committee transcripts. All the investigative files. Plus newspapers. And of course there are the tapes, which go on forever.”

“There was a huge amount material,” he continues. “I soaked myself in it until I knew the people I wanted to tell the story through.”

Mallon eventually settled on a panorama featuring seven main characters. Washington Post reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein are pointedly not among them; the famous investigative tandem is referred to only in passing. Mallon instead recounts the tale theatrically rather than forensically, through the eyes of complicated, fully realized human beings. We come to know intimately the genteel Southerner and hush-money bagman Fred LaRue; the enigmatic ex-spook Howard Hunt; Rose Mary Woods, the loyal-to-a-fault presidential secretary whose infamous tape-erasing “stretch” became part of the Watergate lexicon; the smug and self-regarding cabinet member Elliot Richardson; a surprisingly passionate First Lady Pat Nixon; the mordantly funny queen mother figure Alice Roosevelt Longworth; and of course the Old Man himself.

Once Mallon decided to mix it up with the 37th president, he saw no point in regurgitating yet another Nixon as “mustache-twirling villain.” And the resultant portrait, sympathetic, evenhanded, but hardly exculpatory, arrives at an opportune moment in American politics. Conservatives in the Tea Party era are as disdainful as ever of Nixon’s legacy, with its new bureaucracies and wage-and-price controls and balance of power posturing toward the Soviet Union. The criminality can be mitigated as the handiwork of an adversarial liberal media. But the ideological heresy is business within the family and not so easily brushed aside.

“He was not a small-government man,” Mallon admits. “His domestic policies, in many ways, were more liberal than anything that’s been put forward by Bill Clinton or Barack Obama in the years since. He was for government involvement in medical care. He massively increased funding for the arts. He was for a guaranteed national income.”

Indirectly, Mallon’s novel offers a couple of different ways to absorb this by now familiar litany. One can take it substantively straight-on: The celebrated Nixon-to-China gambit wasn’t confined to the realm of realpolitik; it was a comprehensive worldview.

“What really changes the world,” Mallon’s Nixon is said to believe, “is Tory men with liberal ideas. Churchill had been one, and so is he. That’s what took him to Peking and Moscow, and that’s what will propel him through the whole second term.”

Really, is the deputization of a bold young Daniel Patrick Moynihan to study ways to improve the functioning of the welfare state the worst thing a Republican president could do? The country at that point didn’t seem at all interested in installing a Goldwater to flush out the Augean Stables. Why not try to play the ball where it lies?

Elsewhere, Team Nixon boasts of progressive achievements hidden behind a Southern Strategy smokescreen: “The joke, of course, when it came to all these Wallace votes they were about to inherit” was that Nixon Attorney General John Mitchell “had desegregated ten times more schools than Bobby Kennedy and [LBJ Attorney General Nicholas] Katzenbach and Ramsey Clark put together. Watch what we do, not what we say, Mitchell liked to whisper into the ears of the party moderates, but folks back home in Mississippi listened to the words, as if they were music.”

But then later, in a fit of worry over the real-world consequences of his administration being consumed by Watergate, Nixon declares that domestically the country can run itself. Not so America’s business abroad. Mallon, for his part, offers, “I’m not the first person to say this, but I think he viewed the presidency as essentially the office from which American foreign policy was conducted.”

Mallon mentions that Nixon’s favorite president was Woodrow Wilson: “That seems unlikely to a lot of people, given how Nixon was not a friend of college professors, nor they of him.” But Nixon figured that if there were going to be powerful men crawling on world maps, he should be one of them.

The influence of Wilson might seem the perfect escape hatch through which to expel Nixon from the conservative movement. Through a combination of scholarship, like that of the Claremont Institute’s Ronald J. Pestritto, and the ideological entertainment of Glenn Beck, Wilson is now viewed by many conservatives as a progressive in full ungainly flower—the hollow that separates classical liberalism from modern liberalism.

Would that things were so simple.

President Wilson committed many sins against the principle of limited government. Yet even this allowance presents inconveniences: the targets of Wilsonian police-state overreach were often radicals and socialists. And it remains a fact that he never wavered in his small-l liberal belief in free markets. He was eager, for instance, to rid the country of every vestige of war socialism, which he considered an unfortunate temporary necessity. He took particular relish in vetoing the revival of export credits for Europe to buy American goods. (A veto that Congress would overturn.) As libertarian economist Murray Rothbard noted in A History of Money and Banking in the United States: “To counter the dangerously inflationary postwar boom, President Wilson shifted David F. Houston from the post of agriculture secretary to Treasury secretary, and Houston boldly set about shifting America to a more laissez-faire and deflationary course.”

The continuity of classical liberalism in the person of Nixon, via Wilson, was a central theme of Garry Wills’s brilliant political and intellectual history Nixon Agonistes: The Crisis of the Self-Made Man (1970). Wills asserted that “Wilson’s dream of the League [of Nations] was based on the great myth of the Social Contract, of society as a juridical entity brought into being by grant and codicil, by definition and subscription.” In this telling, Wilson had applied Locke’s theory of the atomic individual to international relations, with “self-determined people[s] entering into the Covenant.”

According to Wills, Nixon

works from the same intellectual assumptions of Wilsonianism. He talks as if he knew and could say ‘what America wants’ in Vietnam. He talks of giving South Vietnam what it wants, as if he knew what that is and could bestow it. In a subtle way, all Nixon’s years of foreign study were distorted by this abstract language about nations and their wants. Only so could he come to office in 1969 still believing in what he called ‘linkage’ as the best tool of diplomacy.

Likewise, Nixon believed that restive inner-city blacks and other “non-succeeders” (Wills’s term) could be assimilated into the Lockean market: managerially bought off, as it were, with a “piece of the action.”

There is yet more of Nixon that latter-day conservatives might arguably be said to own: namely, his bitter cultural populism. As the legendary GOP operative Roger Stone echoed in a 2008 New Yorker profile, “John F. Kennedy’s father bought him his House seat, his Senate seat, and the Presidency. No one bought Nixon anything. Nixon resented that. He was very class-conscious. He identified with the people who ate TV dinners, watched Lawrence Welk, and loved their country.”

Which contemporary conservative lightning rod does Nixon’s resentment here most resemble? Does “Real America” ring a bell?

The connection of un homme serieux to former Gov. Sarah Palin might present the biggest Nixon paradox of all. Mallon remarks that Palin was “preposterously unqualified” for high office—quite unlike Nixon. “There were very few people who were better prepared for the presidency,” he says. In addition to service in the House, Senate, and vice presidency, Nixon spent what he called his “wilderness years”—the Big Apple law firm stint between 1962 and ’68—not merely campaigning for Republicans but traveling and meeting world leaders and opposition figures. “He knew all the important players by the time he entered the presidency,” says Mallon.

Watergate conjures the great What If? of the second Nixon administration. Having rescued Israel in the October 1973 war at its moment of maximum vulnerability, he tilted toward the Arabs following the war’s conclusion, affording Anwar Sadat breathing room with which to boot the Soviets from Egypt. With the goodwill of both parties to the conflict, what kind of permanent settlement might Nixon have been able to forge, thereby saving the world much subsequent trouble? Mallon’s Nixon believes that such a settlement would have enabled him to evade impeachment—a tantalizing counterfactual.

Of course, the real Nixon managed to secure a not insignificant measure of rehabilitation before his death in 1994.

Says Mallon: “He was a great comeback artist. He was a model ex-president, I think. He wrote serious books. He did not take money for speeches, which is, God knows, something you can’t say for Ford, Reagan, the first President Bush, and Clinton. He gave high-quality advice to presidents. Clinton said he wished the memos he got from his own staff were as good as the ones he got from Nixon when he got back from trips. He did that for about 20 years. When you think about it, Nixon’s career as an ex-president was very nearly as long as his career on the national stage.”

Says Mallon: “He was a great comeback artist. He was a model ex-president, I think. He wrote serious books. He did not take money for speeches, which is, God knows, something you can’t say for Ford, Reagan, the first President Bush, and Clinton. He gave high-quality advice to presidents. Clinton said he wished the memos he got from his own staff were as good as the ones he got from Nixon when he got back from trips. He did that for about 20 years. When you think about it, Nixon’s career as an ex-president was very nearly as long as his career on the national stage.”

Even so, this partially rehabilitated Nixon falls far short of the kind of figure conservatives feel comfortable championing today. Yet as Joseph Alsop insisted, the serious man must be taken seriously. Nixonism, it’s true, sported some ugly warts. But one can’t sneeze at his successful steering between the preening moderates of his day (Nelson Rockefeller, George Romney) and the Goldwater right whose electoral drubbing in ’64 was fresh on his mind. Tossing a few bones to the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Humanities, establishing agencies to protect workers and the environment—one can at least sympathize with the notion that these seemed to Nixon like small prices to pay for a smashing electoral mandate.

Nixon is not a man apart from conservatism. To borrow one of the Old Man’s most famous phrases, you might say he’s the cancer within. But in other ways, perhaps also the chemo.

Scott Galupo is a writer and musician living in Virginia.