Back to the Twentieth Century?

No matter how the Ukraine war ends, it won’t restore American global primacy.

Has the Russian invasion of Ukraine “changed everything”? That is, will future historians rank the Ukraine War alongside the two world wars and Cold War of the twentieth century as a transformative event?

Or will the Ukraine war prove more akin to the September 2001 attack on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon? In its immediate aftermath, the catastrophe of 9/11 was widely perceived as a transformative moment, with just about everyone persuaded that it had “changed everything.” As a practical matter, however, its impact proved less than momentous.

So, which will it be? Despite the journalistic certainties you may read in the Washington Post or hear on NPR, the honest answer is that it’s too soon to tell. Only with the passage of time will the full meaning of events currently unfolding in Ukraine become apparent. But I’m willing to put my money on the results being more like 9/11 and less like the world wars and the Cold War: a non-trivial event, to be sure, but one unlikely to divert the history of the twenty-first century from its pre-existing course.

Let’s face it: while not commonplace, horrors like the Ukraine war don’t exactly qualify as rare. In my lifetime alone, a list of comparably bloody episodes would include the partitions of India and of Palestine, the French Indochina War, major conflicts involving U.S. forces in Korea and Southeast Asia, the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan, the Iran-Iraq War of the 1980s, and the so-called Global War on Terrorism, not to mention sundry lesser episodes of interstate violence. (Apologies if I have overlooked your own personal favorite).

The barbarism of the Ukraine war shocks our sensibilities not because it is unique but because it occurs in a part of the world that most Americans have unconsciously (and naively) considered as pacified. That the victims of Russian aggression are pale-skinned is also a factor, albeit one not easily—or comfortably—measured with precision.

By way of comparison, consider the attention that U.S.-based media devote to the war in Yemen. Since 2014, fighting there has claimed an estimated quarter-million lives. Yet while the latest developments in Ukraine make the front page day after day, violence in Yemen qualifies only for occasional mention.

Why this disparity in apparent newsworthiness exists is not exactly a mystery. Politically speaking, not all lives are equal in value. So cumulative body count does not necessarily correlate with a war’s perceived significance. In precincts where political violence is endemic and victims tend to be other than white—Africa and the Middle East offer prime examples—Americans discount the significance of whatever mayhem occurs. So an atrocity in Ukraine, situated in what used to be called Christendom, possesses greater shock value, and therefore news value, than a similar event in Yemen, where the population is Arab and 99 percent Muslim. These uncomfortable realities help to explain why the Ukraine war seems like such an epochal event.

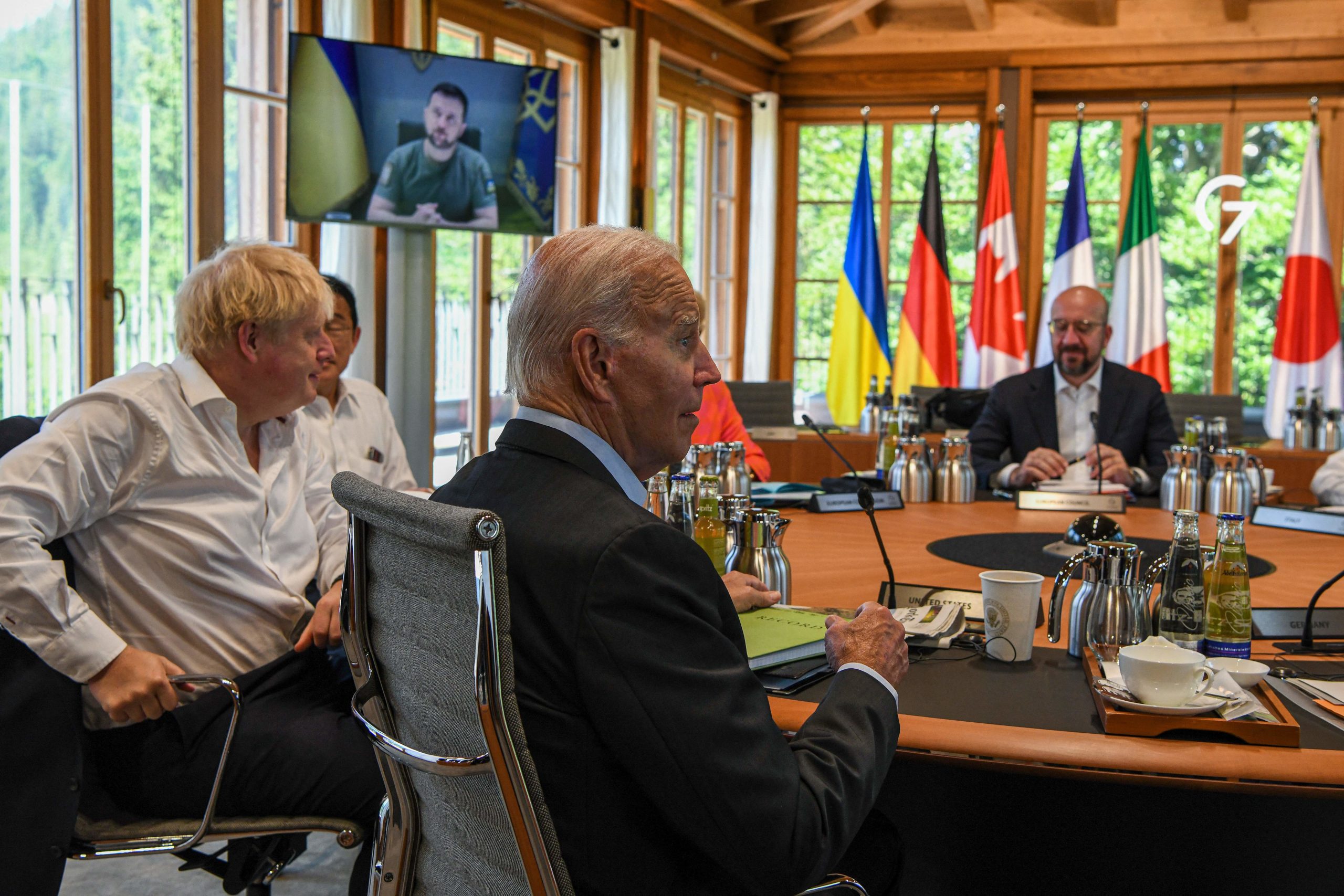

In addition, when viewed from a certain perspective, the war there resurrects hallowed tropes that for most present-day Americans define the very essence of contemporary history. Featuring a cast of easily identified heroes and villains, the Ukraine war pits good against evil and freedom against oppression. In the person of Volodymyr Zelenskyy, the unfolding drama even includes a Ukrainian Winston Churchill. And when it comes to bad guys, the coldly brutal Vladimir Putin serves as a suitable stand-in for the pre-1941/post-1945 version of Josef Stalin.

Take all this into account and the Biden administration’s response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine may seem overdetermined. After all, from the foreign policy establishment’s perspective, we’ve been here before and we know what to do. Harkening back to the Lend-Lease legislation of 1941, providing great quantities of advanced weaponry will provide the wherewithal that will ultimately enable the righteous to prevail. That’s the hope anyway.

But there’s more going on here than simply rescuing poor besieged Ukraine. From Washington’s perspective, the unspoken but implicit aim of the exercise is to stem any further hemorrhaging of American power and prestige. Embarrassed by successive military disappointments in Iraq and Afghanistan, alarmed by China’s emergence as a peer competitor, and haunted by domestic dysfunction that reached an apex of sorts in the January 6, 2021, assault on the Capitol, American political elites badly need a win. A successful proxy war against Russia, assuming that it remains non-nuclear, ostensibly offers an opportunity to demonstrate that the United States is indeed “back,” with the constellation of institutions, arrangements, and norms said to define the American Century still intact.

Well, don’t get your hopes up.

By going to war in Ukraine, more than a few analysts have argued, Putin aims to resurrect some version of Russian imperial grandeur. Allow me to suggest that in a similar way, the United States sees in Ukraine an opportunity to refurbish its own imperial prerogatives. Both aspirations are shot through with hubris. Neither effort is likely to succeed.

A Russian failure in Ukraine will offer cause for celebration, but a Ukrainian “victory,” however defined, won’t restore the United States to a position of global primacy.

Achieved in 1945 and seemingly reaffirmed in 1989, American primacy in recent years has fallen victim to an astonishing mix of miscalculation and ineptitude. The administrations of Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, Barack Obama, and Donald Trump each tried to outdo each other in folly. As the latest twist in the ongoing history-after-the-end-of-history narrative, the war in Ukraine seemingly presents Washington with something of a godsend—an opportunity for the U.S. to recover its mojo and restore its number one global ranking.

Yet even assuming the best case, that happy outcome is unlikely to occur, for at least four reasons.

First, despite all of the fashionable talk in foreign policy journals about the revival of Great Power Competition, Russia does not qualify as a great power. It remains Upper Volta with rockets, and the rockets are not particularly accurate.

Were there any doubts in that score, the less than impressive performance of Putin’s army should resolve them once and for all. If Putin’s war ends in failure for Russia, Ukrainians will deserve high praise indeed. But for the U.S., the outcome will allow few bragging rights.

Second, however the Ukraine war ends, China will still be China. The vast complexities of the U.S.-China relationship, combining elements of rivalry with mutual dependence, will be largely unaffected.

Subscribe Today

Get daily emails in your inbox

Third, regardless of who wins and who loses in Ukraine, the climate crisis will persist, the war itself all but irrelevant to that crisis apart from providing fresh excuses to postpone decisive action.

Finally, whatever happens in Ukraine, these United States of America will remain disturbingly disunited. While the plight of the Ukrainians evokes widespread sympathy, it shows no sign of prompting Americans to set aside their differences on issues like abortion or guns and come together as one in support of a common cause.

For these reasons (and doubtless others as well), future historians will likely classify the Ukraine war as something of a sideshow. To say that the war there qualifies as little more than a distraction may go too far—but not by much. For Americans, more urgent matters languish, all but unattended.

Comments